A Ghastly Version of a Common Rideshare Scam

Uber, Lyft, and other similar services have quickly become a common way to get around. If you’re in or near a city (and increasingly, anywhere else), you can get from point A to point B with nothing more than a smartphone linked to your credit card. These “ridesharing” apps — a misnomer of sorts, but let’s not bother with that today — make it easy, albeit not necessarily cheap — to travel within your immediate region.

Both Uber and Lyft work basically the same way — you boot up the app and tap in where you want to go. Using your phone’s GPS, the company matches you with a nearby driver. That driver picks you up and takes you to your destination, charging you a platform-mandated fee. Your credit card gets charged and the driver gets paid, with the platform taking a cut.

That’s how it’s supposed to work, at least. (And it typically does.) But popularity breeds opportunism. And sometimes, a person looking to use a system to make a few extra bucks isn’t doing so on the up-and-up. If there’s an angle to exploit, someone is exploiting it. Uber and Lyft’s platforms are no different. In this case, if you’re a driver, the trick is to get your assigned rider to cancel after a few minutes. The reason why: in order to protect drivers (and themselves, really), the platforms charge a small cancellation fee (about $5) if you book a ride but, after a tiny grace period, decide to cancel it. Without this protection, riders could effectively summon a driver from across town and, for reasons of anyone’s guess, end up not taking the ride. The driver, having already done some work to get to the prospective rider, would have been left entirely uncompensated but for the cancellation fee.

Some unscrupulous drivers, though, have been exploiting this built-in insurance policy. Here is a really great run-down via Twitter, but to summarize, the app says the driver is only a few minutes away, but a few minutes in, the driver calls the rider to say no, he’s more like 15-20 minutes away. The driver suggests that the rider cancel the ride if he or she doesn’t want to wait, and often, the rider does exactly, that, and then requests someone else. The rider gets charged five bucks and the driver gets a cut of that fee — even though he did basically nothing (except lie).

It’s straightforward and yes, you can apply for a refund and yes, if the driver does it too often, he or she may be kicked off the platform. But what if there were a better, more creative way to get your rider to cancel? What if you could scare your rider into canceling, with nothing more than a picture?

In 2016, Uber was still new enough to China that apprehension over its use — you’re getting into a total stranger’s car! — was widespread. So when a rider booked an Uber, it made sense to spend a little bit of time reading up on the driver. Was he or she driving a relatively new car? Or was there anything else which would make you feel unsafe to take a ride from this driver? Even if it took a bit of time to vet your insta-chauffer (or perhaps you forgot to do so immediately), it may be worth canceling the ride to preserve a little peace of mind.

And that, too, was exploitable. According to the Guardian, “pick-up requests [were] being met by Uber drivers using zombie-like profile shots to scare would-be passengers into canceling their rides.” The prospective riders, already skeptical of the service, wouldn’t want to get into a car driven by someone who looked like he recently feasted on another rider’s brains. Instead, these riders would hit the cancel button, taking the tiny pecuniary hit — and wrongfully enriching their undead drivers.

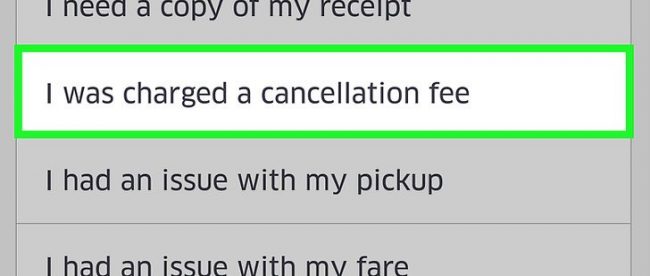

Uber, of course, did what they could to crack down on these “ghost drivers,” as they became known, although that proved difficult in the short term. (“Canceled Due to Driver Thinking it is Halloween Even Though it’s July” wasn’t an option in the app.) Face recognition was the first step toward a solution — Uber has a photo record of each of its drivers, and if the one the driver provided to riders wasn’t relatively close, the system raised a red flag for corporate to review. Further, Uber has since extended the fee-free cancellation window in most parts of the world and, likely, in China as well. Reports of ghost drivers have abated. But new scams, and potentially similarly creative ones, are likely on the horizon.

Bonus fact: You probably don’t know the name Elwood Edwards, but you probably know the voice. Edwards was the voice of AOL’s icon phrases from the 1990s with “you’ve got mail” leading the way. Edwards, though, didn’t make a lot of money for his recordings — he only made about $200 for it., per Inside Edition (that’s a YouTube link if you want to hear him say the phrase). While Edward has had what he described as a “satisfying and rewarding” relationship with AOL through the years, today, he’s not as rich as his hallmark work is famous. So, he finds ways to pick up extra cash. As recently as 2016, Edwards moonlit as an Uber driver.

From the Archives: Remember All Those AOL CDs? There Were More Than You Think.