A Hero’s Welcome

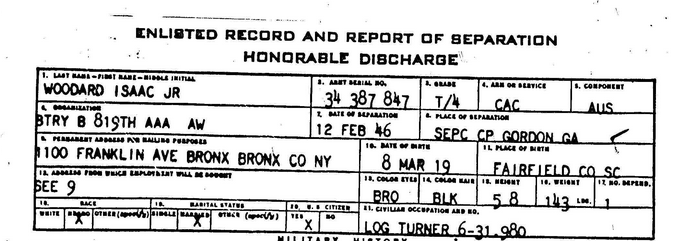

Isaac Woodard served as a sergeant in the United States Army during World War II. He received a total of four medals for his service in both the Pacific theater and in the war generally. As seen above, he was honorably discharged on February 12, 1946, at Camp Gordon (now Fort Gordon) just outside of Augusta, Georgia. (His full record of separation can be seen here.) That same day, Woodard left Camp Gordon and made his way to a Greyhound bus terminal in Augusta en route to North Carolina, where he had family and where a hero’s welcome likely awaited.

Unfortunately, Woodard was an African-American, and some others on his bus cared more about the color of his skin than the uniform that he was still wearing.

Details about what happened on that bus are unclear — this all happened decades before everyone had a camera in the their pockets — but the handful of reports after the event tend to agree on a few details. The bus driver, for reasons unclear, didn’t want Woodard on the bus, claiming he had been a disturbance. No confirmed details as to why ever surfaced; Woodard’s Wikipedia entry states that he was drinking beer with other soldiers on the back of the bus, while subsequent court testimony notes that Woodard wanted the driver to wait so he could use the restroom. Regardless, the driver pulled over in South Carolina and called for the police, who forcibly removed Woodard from the bus and demanded to see his discharge papers — which, given that he had just been discharged a few hours earlier, he was able to easily provide. They arrested him anyway, and worse, the officers beat Woodard repeatedly and jailed him overnight, where he was likely beaten some more. Even the chief of police, a man named Linwood Shull, was directly involved in the beatings.

He went before the judge the next day and was convicted, but the extent of his injuries were much more permanent than the guilty verdict and $50 fine his alleged crimes cost him. The beatings and lack of immediate medical care — it took two days before he saw a doctor — cost him his vision. While some reports claimed that his eyes had been gouged out, that wasn’t exactly the case, but the effect was similar. Both of his eyes had ruptured. Woodard would never see again.

The beatings had also caused partial, temporary amnesia, and no one knew who he had intended to visit. It wasn’t for another three weeks that he therefore was able to connect with his relatives in North Carolina, and that only occurred because they had reported him as missing. For months, the assault on Woodard went mostly unreported. But in September, after the NAACP elevated the assault into the national conversation, it became the talk of the land. President Harry Truman stepped in and insisted that the Department of Justice investigate. Ultimately, the DOJ indicted Shull. But the trial wasn’t much of one. Shull admitted to the assault and that his actions caused Woodard to lose his vision, but the jury nonetheless acquitted him — to the approval of those in the gallery.

While the loss in court was a blow for the civil rights movement, Woodard’s injuries were a catalyst for on-going change. In July of 1948, President Truman issued Executive Order 9981, desegregating the U.S military. Woodard’s travails are often cited as one of the reasons Truman pushed through desegregation.

Bonus Fact: President Truman visited Disneyland in 1957, well after he left office and had mostly withdrawn from the political sphere. Nevertheless, according to Wikipedia, he declined taking a ride on the Dumbo the Flying Elephant ride. Apparently, he did not want anyone getting a picture of him, a loyal Democrat, with an elephant, the symbol of the Republican Party.

From the Archives: Rosa Parks’ First Ride: You know the story of Rosa Parks’ refusal to move to the back of the bus. But what about the other time she had a run-in with the very same bus driver?

Related: A book (4.6 stars, 18 reviews) on Truman’s efforts to desegregate the military.