Candy Barred

Pictured above is a Baby Ruth candy bar — a chocolate-covered mix of peanuts, caramel, and chocolate nougat. If you look carefully at the bottom-right, you’ll see the logo of Major League Baseball (MLB). In 2006, Baby Ruth became the “official candy bar” of the league.

That probably wouldn’t have made Babe Ruth happy.

In 1884, a Major League ballplayer Ned Williamson hit 27 home runs — the most ever in any one baseball season. If you’ve never heard of him, that’s OK, because most people haven’t. His single-season record stuck until 1919 when Babe Ruth — arguably the best player in Major League history — slugged 29 homers. Ruth’s record lasted one year — but he didn’t mind. In 1920, Ruth shattered his own record, hitting 54 home runs and cementing himself as a household name throughout the nation. A year later, he’d best that inconceivable mark, crushing 59 homers over the course of the season. Babe Ruth was a superstar.

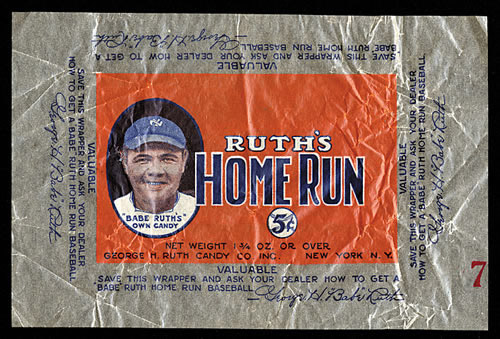

Kandy Kake was invented a few years before Ruth’s emergence on the baseball field. Kandy Kake was a candy bar produced by the Curtiss Candy Company but, much like Ned Williamson, no one really cared about it and its existence has been mostly forgotten about. That’s because, in 1921, the Curtiss Candy Company changed up the recipe a bit and gave it a new name — Baby Ruth. If the timing seems too odd to be a coincidence, Babe Ruth didn’t seem to care — at least not immediately. But by 1926, perhaps because the candy bar was selling in droves, Babe Ruth decided to do something about it. He created his own brand of licensed chocolate bars, called “Ruth’s Home Run,” as seen below (the wrapper, at least), and applied for a trademark for the product.

And then the lawsuit came. But it wasn’t the baseball player who sued — it was the Curtiss Candy Company. The candy bar maker claimed that Babe Ruth’s new product’s trademark application violated Curtiss’s intellectual property rights, and asked the U.S. government to reject the application. The candy company won.

While the court declined to rule whether Baby Ruth was acting in bad faith in apparently free-riding off of Babe Ruth’s fame, the candy company offered an explanation anyway. Baby Ruth, they asserted, wasn’t named for the baseball player after all. Instead, they claimed, the candy was named after Ruth Cleveland, the first daughter of former U.S. president Grover Cleveland. That’s unlikely — “baby” Ruth Cleveland was born in 1891, thirty years before the candy bar came out, and she died of diphtheria in 1904 and had almost entirely fallen out of the public consciousness. Most likely, the official story was a well-placed lie in order to make it difficult for Babe Ruth to claim any infringement or an implied endorsement.

Of course, that implied endorsement is very strong. When Baby Ruth and MLB entered into the above-noted “official candy bar” deal, the press release noted that “Baby Ruth consumers are 22% more likely than the average population to be MLB fans, and are 18% more likely than the average population to have attended a MLB game in the past year.” In short, Babe Ruth fans like Baby Ruths, and that makes no sense for a candy bar named after a long-dead non-baby that most everyone had forgotten about.

Bonus Fact: Babe Ruth was such an established superstar that, years after his retirement, he became a rallying cry among World War II soldiers — Japanese soldiers. In taunting American troops, according to one book, Japanese troops took to yelling “to hell with Babe Ruth.”

From the Archives: Swing and a Miss: The girl who struck out Babe Ruth — and then found herself and her gender banned from Major League Baseball.

Related: Baby Ruth, the box set.