Charles Bernard’s Unexpected Vacation

In today’s world, news travels quickly. Technology can bring us the live video of events occurring thousands of miles away as they unfold. Tweets can move faster than earthquakes. And email outpaces the stamp-and-paper post so dramatically that the latter is now sometimes called “snail mail.”

Two centuries ago, this wasn’t the case. News travelled very slowly — sometimes, with bloody results. The War of 1812 provides a famous example. On December 24, 1814, the United States and the United Kingdom agreed to end the war, signing what is now known as the Treaty of Ghent (in what is now Belgium). However, it took about a month for news to reach the Americas, and for ten days the following January — despite the fact that the war was over — the two nations fought the Battle of New Orleans. The battle ended when the UK forces learned of the treaty and withdrew, but not before approximately 300 people lost their lives and thousands of others were injured.

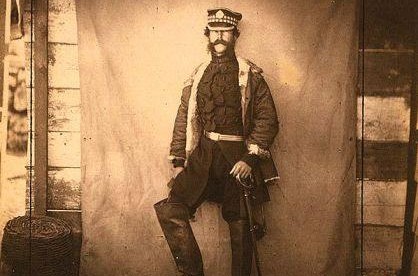

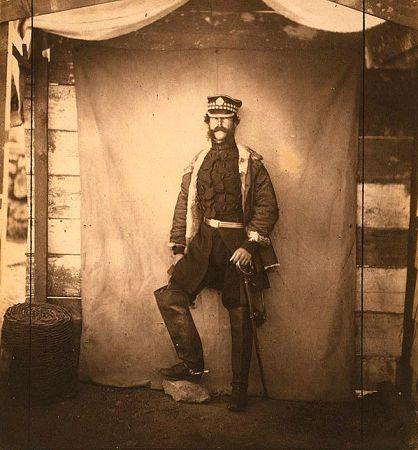

That wasn’t the only example of slow news disrupting the War of 1812, though. Just ask Charles Bernard, pictured below.

Despite the outfit, Bernard wasn’t a military man. He was, however, a sea captain — one who, a few months before the war broke out, took his ship, the Nanina, and its crew to the South Atlantic to go seal hunting. He was going away from where the actual fighting was — it was happening in and around North America, while he headed south — so one would think that the war would have passed Bernard by. But Bernard’s journey took him to the Falkland Islands, the British-controlled archipelago off the coast of Argentina. Despite being thousands of miles from the British Isles, Bernard was near enemy land — at least, in theory. But in practice, they weren’t all that concerned. Even though Bernard and his crew learned that the U.S. had declared war on the UK, they didn’t give it much thought and continued on their expedition.

Bernard and crew set up camp at New Island, a small island in the west of the archipelago. (Here’s a map.) In April of 1813, the company went to Eagle Island (now Speedwell Island — it’s in the south, toward the center of that map) as part of their sealing endeavors. What they found, though, was more than seals — they found people. Specifically, the Nanina came across the Isabella, a shipwrecked British ship which had set off from Australia and was hoping to reach England. Bernard, showing compassion, decided to help and invited the crew of the Isabella aboard the Nanina. The fact that the two sides’ home nations were at war was a non-issue because, as it turned out, the captain and crew of the Isabella had no idea that the two nations were at war. Nevertheless, Bernard decided to inform his new guests of the war being waged in other parts of this world.

This turned out to be a huge mistake.

According to the book “The Falklands & South Georgia Island,” Bernard and four of his men took a smaller boat back to New Island to retrieve more provisions, given their guests. And while Bernard was away, the guests took advantage of the situation and took over the Nanina. The Isabella’s crew, now in control of what they viewed as an enemy ship, simply set off to sea and left the enemy behind. Bernard and his men were castaways.

Despite the Falkland’s reputation for terrible winters, Bernard and the others beat the odds and survived the ordeal. Eighteen months after being left for dead, they were rescued by a pair of British whaling boats. Even though that rescue occurred in November of 1814 — a month before the end of the war — the British seamen treated Bernard and company as their guests. The former castaways finally made it back to the United States about two years later.

Bonus fact: To some degree, the War of 1812 itself was a creation of slow information flows. The U.S. declaration of war was, in part, a reaction to the UK’s “Orders of Council.” These Orders, per Wikipedia, were designed to harm Napoleon in his efforts against the British; the Orders “required all shipment to stop in English ports to be checked for military supplies that could have aided France.” The U.S. saw this as an undue restriction on international trade and threatened war if the laws weren’t repealed. On June 16, 1812, the UK repealed the Orders, but no one in the U.S. knew that. Two days later, the U.S. declared war on the UK, and by the time both sides realized that a major point of contention was no longer one, it was too late — the ambiguity of war had set in, perpetuating further hostilities.

From the Archives: Easy Does It: That time in the Spanish-American War when one side won a battle because the other side didn’t know that the two nations were at war, so they didn’t fight back.

Related: “Marooned: Being a Narrative of the Sufferings and Adventures of Captain Charles H. Barnard,” Bernard’s autobiography outlining the ordeal. The only review (which is published twice for some reason) gives the book four stars but calls it “a must, must read.”