Co-opted Hiss-tory

Snake oil is a generic term meaning “a substance with no real medicinal value sold as a remedy for all diseases.” Historically, the term most likely comes from the use of oil derived from Chinese water snakes as a topical lotion; Chinese immigrants working on the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad in the 1860s would use it to alleviate joint pain. This ancient Chinese remedy — a term which often induces guffaws even today — was howled at by other medicine salesmen, who called it out as a scam. In time, the term “snake oil” developed a negative connotation.

But maybe it shouldn’t have.

In the mid-1980s, a California psychiatrist named Richard Kunin (who, as Scientific American points out, had a background in neurophysiology research) decided to explore the question — was snake oil quackery? Or was it a perhaps a legitimate treatment for joint pain, like the Chinese laborers from a century-plus prior claimed it was? He shared his findings in a 1989 letter to the Western Journal of Medicine (pdf available here). Snake oil — especially the oil from the fatty tissue found in the Chinese water snakes — was unusually high in omega-3 fats. And, as Kunin concluded, this meant that it could actually do what its advocates claimed: “snake oil is a credible anti-inflammatory agent and might indeed confer therapeutic benefits. Since essential fatty acids are known to absorb transdermally, it is not far-fetched to think that inflamed skin and joints could benefit by the actual anti-inflammatory action of locally applied oil just as the Chinese physicians and our medical quacks have claimed.” In other words, Kunin believed that snake oil actually worked. And subsequent research suggests that he was right.

Unfortunately, while Kunin’s conclusions are likely mostly correct, there’s one significant omission. The Chinese snake oil came from water snakes (which, perhaps coincidentally fed on fish which themselves contained high amounts of omega-3 fatty acids.) American-sold snake oil came from rattlesnakes, which, as both Scientific American and Kunin both point out, do not have anywhere nearly the omega-3 amounts needed to provide the promised therapeutic benefits.

So next time someone comes trying to sell you some snake oil, don’t say “no thanks.” Instead, ask “from what kind of snake?”

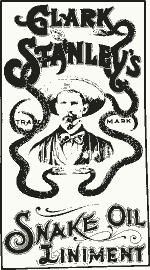

Bonus fact: Perhaps the most well-known snake oil scam was that of Clark Stanley’s, a man later known as the Rattlesnake King in the late 1800s and into the 1910s. His snake oil, the label of which is pictured above, didn’t work — but not because rattlesnake oil is low on omega-3s. It didn’t work because it didn’t contain any snake oil at all. In 1916, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Chemistry analyzed Stanley’s liniment, finding that it contained mostly mineral oil and only 1% fatty oils, which the Bureau concluded was “probably beef fat.” Stanley pled no contest and accepted a $20 fine.

From the Archives: Five Figures of Snake Oil: A really big, really expensive device which just doesn’t do what it claims to do.

Related: A real Chinese water snake in an acrylic block. For the person who has everything…? Seriously, who buys this?