Extreme Tag

The game “Tag” is pretty simple. One person is “It,” and remains “It” until he or she touches another person with his or her hand. Then, the touched person (or, in the game’s parlance, “tagged” person) becomes “It,” and the process repeats itself. The game has no obvious end — typically, the players run away from “It” until everyone gets tired/bored or it’s time to come inside for dinner. In some sense, if you’ve ever played Tag, you’re still playing — if you’re not “It,” someone is, and the game is simply in a perpetually paused state. There are exceptions to this, of course — for example, what happens when “it” dies? — but by and large, it’s true. Of course, it’d be kind of strange if someone from high school showed up at your door, grabbed your shirt, and screamed “Tag! You’re It!”

Unless you’re one of ten guys, originally from Spokane, Washington, for whom that experience is called “February.”

As reported by the Wall Street Journal, these ten friends were playing an aggressive game of tag as their senior year closed. On one of the last days of school, “It” was a guy named Joe Tombari. Tombari launched a plan to tag a specific friend, but that plan was thwarted when the friend ended up going home early. Tombari went to the guy’s house, but when Tombari’s target locked himself inside his car, avoiding Tombari’s tag, Tombari effectively became It for life. (See? Tag truly is the game that never ends.) Eight years later, Tombari and a group of friends were commiserating over this sad fact, and that sparked an idea — an ongoing, almost-everything-goes game, except that tags only count in February.

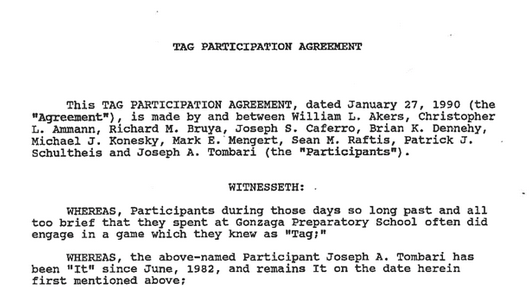

There are other rules, too, drafted by participant (and then first-year lawyer) Patrick Schultheis and signed to by all parties. When asked if you are “It” by another player, you must answer truthfully. Each participant has to make a $25 donation to their high school each year. And there’s no backing out — the document is a contract which allows the other participants to force a lax one into playing. (The full rules can be seen here.)

The game has been going on for over two decades, and as the group has scattered across the United States, the storylines have become increasingly ridiculous. One “It” hid in the trunk of a car to catch his prey (Tombari, as it turned out), scaring his target’s wife in the process — she fell backward and tore a knee ligament. Another participant, upon taking a job as Nordstrom’s chief marketing officer, inquired about office security, as he didn’t want nine particular non-employees to gain access to the office for 28 or 29 days a year. Another year, the “It” camped out in the bushes outside his target’s apartment for two nights — but the target was away for the weekend.

The game is ongoing, to be picked up again in February 2014. And unfortunately, they don’t seem to be accepting more participants.

Bonus fact: This generation of children may find it difficult to get involved in a game of tag — not as adults, but as kids. A handful of elementary schools have decided to prohibit the game from their recesses and playgrounds, with reports coming in from the Washington Post, USA Today, ABC News, and many others.

From the Archives: February 30th: February has either 28 or 29 days, usually.

Related: A set of six kickballs, in case your school has banned Tag.