The Slave Who Shipped Himself to Freedom

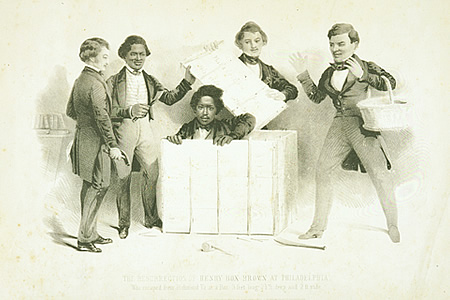

In March of the subsequent year, Brown decided he wanted out — out of the plantation, out of slavery, and out of the American South. With about $160 to his name and legal climate unconducive to his hopes, Brown needed to get creative. While many American slaves looked toward the Underground Railroad as a means to freedom, Brown decided to go a different route — the regular, above-ground, actual-railway railroad. All he needed was a little help and a very big crate. Because on March 23, 1849, Henry Brown shipped himself to life as a free man.

Brown gave about half of his wealth — $86 — to a Southerner sympathetic to the abolitionist cause named James C. A. Smith. Smith, in turn, contacted a man named James Miller McKim, a Presbyterian minister in Philadelphia who was a leader in the movement. McKim agreed to receive a package from Smith which, if everything went right, would contain Brown. Brown intentionally burned his hand with sulfuric acid in order to miss out on work and, instead, entered the crate. Over the next 27 hours, he was in the custody of the Adams Express company (now an investment fund, then a shipping company) as he, in crate, made his way from Richmond to Philly. Over the course of his journey, he’d go by wagon three times, rail three times, and ferry and steamboat once each. But in the end, he emerged, alive and free.

As one would expect, Brown became an icon for the anti-slavery movement — but, that, too, was fleeting. Noted abolitionist Frederick Douglass was publicly upset with Brown for publicizing his escape route; Douglass believed that by revealing his method, Brown prevented others from following suit. But more importantly, in September of 1850, the United States passed the Fugitive Slave Act, requiring that any runaway slaves be brought back to their slave masters. Brown fled to England and became a traveling showman. While he returned to the United States after the Civil War, he did so without any meaningful notoriety — the details of his death are unknown today.

Bonus fact: Henry Brown isn’t the only person who mailed himself to freedom. As reported by the BBC, in 2008, a man serving a seven-year jail sentence in Germany couriered himself outside the prison walls. Once he was outside the gates, he climbed out of the box and escaped. The jail’s warden admitted that they were unable to find him after.

From the Archives: Pole Position: The bonus fact features another person who tried to mail himself.

Related: “Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown,” his autobiography, written in 1851. Also, “Henry’s Freedom Box,” a children’s book about Brown’s story. 4.8 stars on 34 reviews.

Leave a comment