General Order Number Eleven

General Order Number Eleven was short. Three items were wrapped into one edict. It read:

- The Jews, as a class violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department and also department orders, are hereby expelled from the Department within twenty-four hours from the receipt of this order.

- Post commanders will see to it that all of this class of people be furnished passes and required to leave, and any one returning after such notification will be arrested and held in confinement until an opportunity occurs of sending them out as prisoners, unless furnished with permit from headquarters.

- No passes will be given these people to visit headquarters for the purpose of making personal application of trade permits.

In short, “no Jews allowed,” effective nearly immediately.

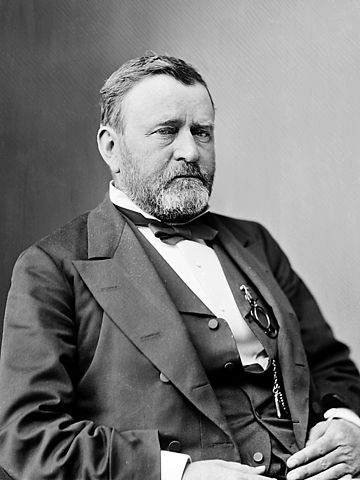

But the “Department” wasn’t a section of Nazi-controlled Europe or Inquisition-era Spain. The edict wasn’t issued by Adolf Hitler. It was issued by Ulysses S. Grant, who would later be President of the United States. The year was 1862, and the “Department” was the “Department of Tennessee,” an area consisting of western Tennessee, western Kentucky, and northern Mississippi.

In the spring of 1862, Grant, then general of the Union Army, made great advances in the American Civil War, taking control of much of the areas listed above. His next goal was to march south, with Vicksburg, Mississippi, in his sights. But commanding the Army wasn’t his only job. Despite the war, the North and South continued to have some limited amount of economic activity between the two, with the North buying cotton from Southern plantations. Grant was also charged with enforcing the Union-set limits on the amount of cotton which could legally be imported into the North. But illegal cotton dealings were rampant and legal ones were a bother; merchants would come to Grant’s headquarters seeking permits, as one historian noted. Grant saw most of these merchants as war profiteers, and on December 17, decided to ban them from the region by proclamation. But for some reason — Slate notes that most of the “smugglers and traders […] were not Jewish at all” — Grant’s order targeted Jews, and all Jews in the area, for that matter.

The order was of limited effectiveness (against Jews, that is; it was almost entirely ineffective against smugglers because most weren’t subject to the order) for two reasons. First, the order didn’t get distributed immediately, as communications lines were disrupted by Confederate raids just hours later (unrelated to the order, though). Second, word of the order spread throughout the country and eventually to President Lincoln, who ordered Grant to rescind it. He did so, officially, on January 18 of the following year. Many Jews in the area were, indeed, displaced during that month, however, and the order kindled fears of anti-Semitism throughout the country. As Slate further said, “It brought to the surface deep-seated fears that, in the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation, Jews might replace blacks as the nation’s most despised minority.” Further, for perhaps the first time, American Jews needed to openly consider whether to vote for candidates who were good for the country but bad for Jews themselves.

Grant, for his part, claimed to not intend the anti-Semetic aspects of the order. His headquarters showed some surprise when Jews who were not smugglers were relocated, even though the plain language of the order included all Jews. Grant also later stated that he didn’t draft the order and hastily signed it without reviewing it, but other communications by Grant around that period also singled out “Jews” or “Israelites.” To his credit, though, during his term in the Oval Office, Grant became the first U.S. President to attend a synagogue service.

Bonus fact: The synagogue Grant visited, Adas Israel Congregation in Washington D.C., has two other historical firsts to its history. According to its website, it was the first synagogue in the United States to be addressed by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Dalai Lama.

From the Archives: The Last Jew in Afghanistan: Really, there’s only one (known) Jewish person living there.

Related: In 1920, ex-President William Howard Taft gave an address to the Anti-Defamation League discussing anti-Semitism in the United States. Amazon has a copy of his remarks, but it costs just under $200. More on point: “When General Grant Expelled the Jews” by Jonathan D. Sarna. 4.2 stars on 33 reviews, available on Kindle.