How Matthew Broderick Helped Shape American Computer Law

Matthew Broderick’s best movie was Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. In the film, Broderick’s character, a teen named Ferris Bueller, was able to skip school while avoiding the consequences of an absenteeism policy he ran afoul of many times over. In the movie, Ferris is the hero, but from a public policy perspective, truancy is a problem and one can imagine a government wanting to take action to prevent or reduce it. (In fact, in some areas of Los Angeles, repeat truancy is punishable by a fine.) But in deciding how to best find a solution to the problem, one would hope that the relevant legislators would understand what truancy is, how it works, and how to best prevent it. And if they didn’t know that beforehand, they could bring in well-qualified, expert witnesses to educate them on the topic. One would further hope that the lawmakers wouldn’t simply watch part of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and use that as their basis for addressing the issue.

But when it comes to computer crimes, that’s basically what Congress did. In 1983, the government began work on what would later become the “Computer Fraud and Abuse Act” or CFAA, a law originally intended to prohibit significant, unauthorized access to government computers. But it was the early 1980s and most legislatures didn’t know much about computers. So they turned to a Matthew Broderick movie: WarGames. Slate explains:

A 1983 congressional hearing on computer security began with a clip from WarGames in which the main character [played by Broderick] hacked into a school computer in order to change his grade (“a sequence I’m told is quite realistic in terms of what real hackers do,” announced Rep. Dan Glickman).

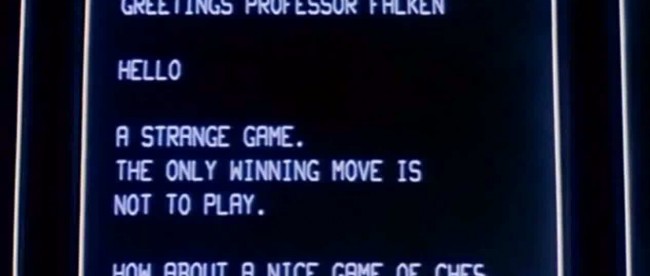

Had Congress kept watching — and given the popularity of the movie, it’s likely that many had already seen the whole film — they would know that this “quite realistic” hacker didn’t stop by changing his grades. He accidentally connects up with a government war games simulator run by NORAD (that’s short for “North American Aerospace Defense Command”) and put humanity at risk as a result — only to miraculously save it. Through a series of impossible events, not only did Broderick’s character accidentally almost launches a series of nuclear warheads at the Soviet Union, but he also somehow manages to avert the disaster by teaching a computer how to teach itself about higher-level philosophical concepts. To say WarGames is unrealistic is a vast understatement.

Nevertheless, Congress and then-President Ronald Reagan were sufficiently spooked, as CNET recounts:

“WarGames,” the first movie to profile hacking so prominently, spilled over into unrelated discussions about national security: a biography of Ronald Reagan recounts how the president asked a group of Democratic congressmen meeting at the White House to discuss arms reduction if they had watched the movie. Rep. Vic Fazio, a California Democrat, recalled Reagan saying: “I don’t understand these computers very well, but this young man obviously did. He had tied into NORAD!”

And as a result, Congress drafted the CFAA. The law was originally intended “to criminalize ‘only important federal-interest computer crimes,’” per George Washington law professor Orin Kerr (via Business Insider), but as laws often do, CFAA became more and more stringent over time. There have recently been a spate of cases where, as the Electronic Frontier Foundation notes, prosecutors argue “that violating a private agreement or corporate policy,” including, perhaps, violating those billion-words terms of service agreements no one ever reads, “amounts to a CFAA violation.” (Here is a list of notable CFAA cases if you’d like to explore further; the Swartz, Drew, and Drake cases are particularly interesting although some take tragic turns.) If that seems like something not based in reality, that may be because it’s based in part on a 1983 sci-fi movie.

Bonus Fact: Another effect WarGames had on the government: it improved NORAD itself. When WarGames came out, the real NORAD didn’t have anywhere near the gadgets and gizmos that the fake NORAD had in the film. In 2008, Wired put together an oral history of the movie and spoke to a guy named William Lord, then a commander in the Air Force Cyberspace Command. “A few years [after the movie came out],” said Lord,”I was an executive officer with the Air Force Space Command stationed at Norad near Cheyenne Mountain. And I’m wondering, ‘Gee, where can we get such cool-looking displays?’ It was a good forcing function. It required us to all of a sudden say, ‘If it really can look like this, why doesn’t it?'”

From the Archives: Thermonuclear War and Taxes: Had WarGames been real and played out differently, the world may have come to an end — but the few survivors would still have to pay taxes.

Take the Quiz: Name all the games that Joshua, the WarGames computer, can play.

Related: WarGames.