I Can’t Believe It’s All Butter

That — that is butter. But you knew that already. If you’re living in the United States and are east of the Rocky Mountains — well, east of the Mississippi, for sure, but it’s still likely true if you’re east of the Rockies — that’s what a stick of butter typically looks like. They come, typically, four to a box, stacked two by two.

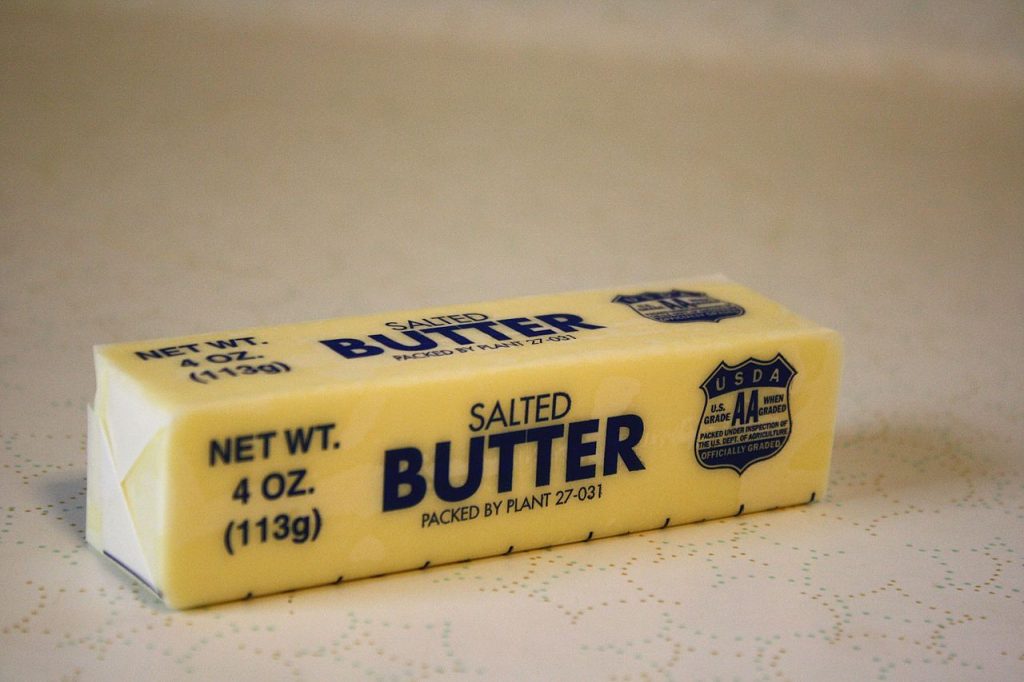

If you’re an American on the west coast, though, something’s amiss — that’s not what butter looks like. (If you’re outside the United States, well, sorry. But the story is still pretty interesting.) For all you Californians, Utahns (yes, that’s how it’s spelled), Idahoans, etc., butter comes in a more squat, fat bar like the one below, packaged four in a box, but lined up vertically in a row.

That’s right: east coast butter looks different than west coast butter. And, by and large, the two populations aren’t aware of the butter-buying habits of the other. But regardless, why does America country need two different sized sticks of butter?

We don’t. But we’re stuck with it.

Butter is a milk byproduct — dairy farmers take excess milk and churn it to separate the butterfat from the buttermilk. The butterfat, once cleared of as much of the buttermilk as possible, is combined with water (at about a 4:1 butterfat to water ratio) and then shaped for packaging. That’s basically it. The important part, for our purposes: If a region’s milk production isn’t enough to meet the demands of the milk-drinking public, there won’t be any left over to turn into butter.

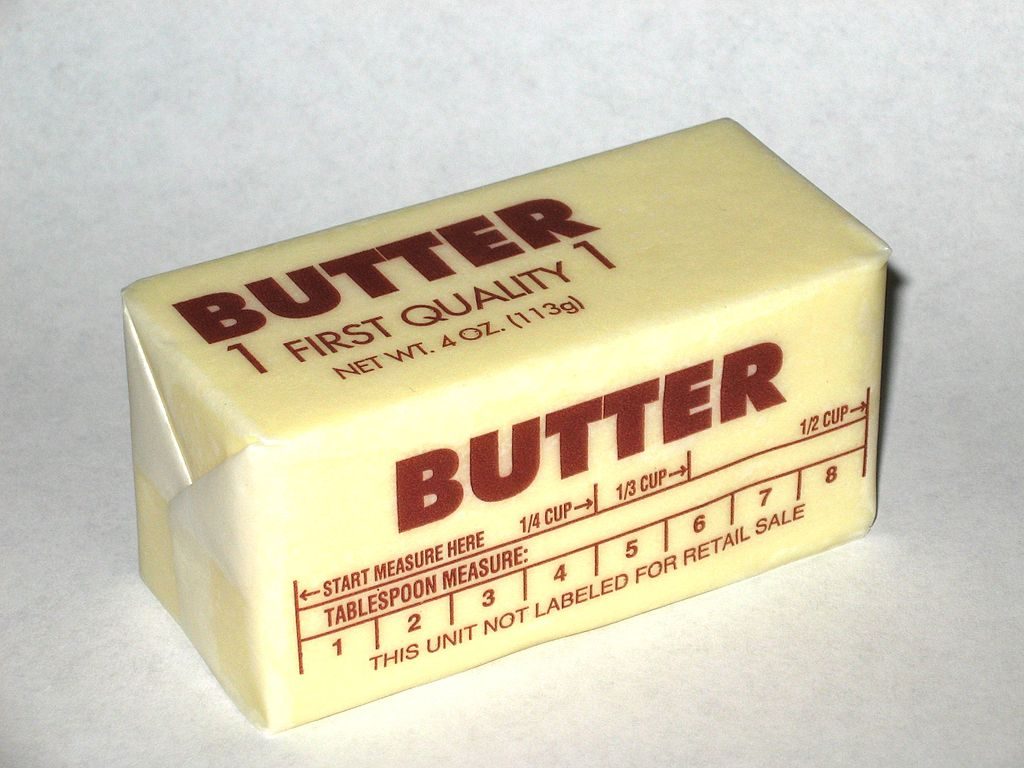

If you were in Elgin, Illinois in the early part of the 20th century, that wasn’t a problem — the Midwest had more than enough milk to meet the region’s needs. An Elgin company turned the area’s leftovers into sticks of butter using machines called butter printers — kind of like early 3D printers, but they were only used to shape butter and could only make one shape of it. The end result was the butter stick shown at the top and those sticks of butter spread (sorry) throughout the country. As more and more dairies had access capacity, more and more companies made and shaped butter, and they used the same machines as the ones in Elgin — and therefore made the same sized sticks. In fact, these longer, thinner sticks are now known as “the Elgin.”

But on the west coast, they weren’t making Elgins — they weren’t making butter at all. American Public Media radio show Marketplace caught up with John Bruhn, formerly a professor at the Dairy Research and Information Center of the University of California Davis, an expert on the dairy industry. Per Bruhn, “in the 1960s, the West Coast was [deficient] in terms of milk production to make dairy bi-products like cheeses and butter. All our milk went to fluid needs. Whole milks, low fat milks and non-fat milks, for example.” So, almost no butter was made west of the Rockies.

By the time western dairy production ramped up, there weren’t a lot of Elgin-making butter printers left. New technology in the butter-making world led to new machines, ones which created fatter, shorter sticks (now called Western Stubbies). The California dairies ended up buying these new machines, making different-sized sticks. But in the east, tradition won out — instead of upgrading to the new machines, companies just kept repairing their old butter printers. Today, one can get either type of butter printer.

And both are needed because tradition dictates it — the custom of bifurcated butter has become a fact of life in the dairy world. As The Kitchn notes, “today, companies like Land O’ Lakes continue to produce butter of both sizes to satisfy the stick preferences of the respective coasts.” Western butter is short and squat; eastern butter long and thin. Putting shape aside, though, it’s the same product — butter is butter.

But there’s one arena in which east coast butter wins the battle: butter dishes, even those in the west, are almost always designed for the Elgin. Sorry, Utahns.

Bonus fact: In Iowa, it is illegal to advertise one’s margarine as butter (regardless of the size of the stick). In Wisconsin schools, prisons, or state-run hospitals, the law is even more stringent: “the serving of oleomargarine or margarine to students, patients or inmates of any state institutions as a substitute for table butter is prohibited” (with an exception for specific health concerns.)

From the Archives: Dye It: How butter turned margarine pink.