I, Zombie

Sometime in 2004 or thereabouts, a man only identified as Graham was suffering from severe depression. He decided to take his own life. He ran a bath, got in, and brought in some sort of electrical appliance with him.

Eight months later, Graham informed his doctor that the suicide attempt was a success, and that Graham was dead.

If that sounds impossible to you, that’s because it is. But Graham didn’t agree. He was convinced that his brain stopped functioning on that day, in that bath tub — and he even sat down with New Scientist to discuss his “death” after he began on the road to recovery. As he told the reporter covering his story, he somehow convinced himself he no longer had a functioning brain. The sound of his own voice frustrated him because he believed he couldn’t speak, given that he was brain dead. He stopped brushing his teeth because dead people don’t need them. He also stopped taking his medication — given that it was for a mental disorder and that he believed he had no brain, that actually made some sense, in a perverse way. His life was a living nightmare — he told New Scientist that he “had no other choice than to accept the fact that [he] had no way to actually die.” After all, he was already dead, except for the inconvenient (to him) fact that he happened to not be.

Graham likely suffered from something called Cotard Delusion, also known as “Walking Corpse Syndrome,” a rare disorder first described in 1880. A French neurologist named Julian Cotard (hence the name) had a patient, only known as Mademoiselle X, who denied the existence of much of her body and, perhaps more importantly, of her need to eat. The negation of reality was something Mademoiselle X truly believed, and it ultimately led to her death. She died of starvation.

Per Dr. Cotard, this extreme rejection of one’s corporeal reality as the defining characteristic of the syndrome and, in the rarest of cases, may even mean that the patient believes him or herself to be dead. The syndrome, in modern times, isn’t considered a distinct diagnosis but rather a part of other, “underlying disorders” (per the linked-to study). As such, there have been some successful attempts to treat the condition — with Graham being one such success.

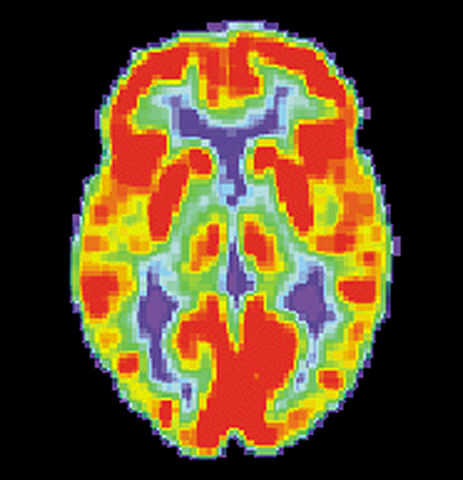

But don’t think that the delusion is something consciously controlled. As Graham’s case demonstrates, the subconscious “believes” the same things that the conscious self articulates. Graham claimed that his leg hair fell out in clumps, with no obvious or external cause. He also claimed that his desire to smoke cigarettes waned, as they no longer seemed to have an effect. But perhaps most striking was the one oddity which wasn’t based on Graham’s assertions. A neurologist who performed a PET scan (a normal one is above) on Graham’s brain noticed that the results were remarkably similar to that of someone who was asleep or under anesthesia, even though Graham was very much awake — he was walking around, interacting with others during the brain scan.

The good news for Graham is that he’s no longer dead, or even mostly dead. Through treatment, he tells the New Scientist, “I don’t feel that brain-dead any more.”

Bonus Fact: The words “mostly dead,” above, link to a YouTube clip from the 1987 movie The Princess Bride. That’s the only scene in which comedian Billy Crystal (as “Miracle Max”) makes an appearance. But that was enough to cause some damage. Mandy Patinkin, who played the vengeance-seeking swordsman Inigo Montoya, suffered one significant injury during the course of the filming. It wasn’t due to the sword fights, though; it was because of Crystal’s jokes. Patinkin told NPR that “[he] bruised the muscles on the side of [his] ribs because [he] was so tight trying not to laugh.”

From the Archives: Get Ready for the Zombie Apocalypse: Why the U.S. government has a guide, advising people how to prepare for an influx of zombies.

Related: A zombie.