Konged

In 1981, Nintendo released the video game Donkey Kong. According to the book “Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life,” the game was originally intended to be a snippet from the Popeye universe, with the protagonist Popeye charged with saving his girlfriend, Olive Oyl, from a brutish and less intelligent Bluto. But Nintendo failed to obtain a license for the game, and instead, the game’s lead designer changed the characters. Popeye became Jumpman, named for his one skill (jumping). Olive Oyl became Lady. And Bluto became Donkey Kong.

Donkey Kong wasn’t, directly, named after the cinema sensation King Kong, although the character was certainly inspired by the movie monkey. While no canonical explanation behind the name “Donkey Kong” is widely agreed upon, one story has the word “Kong” coming from the Japanese word for “ape,” while “Donkey” stems from the fact that the animal of the same name is stubborn, making the video game antagonist a “stubborn ape” (or worse). Regardless, the seemingly obvious association between Donkey Kong and King Kong was enough for Universal Studios, company behind the King Kong movies. Universal was looking to break into the video game business, and saw this potential intellectual rights infringement as a quick way to gain entry.

While some of Nintendo’s partners settled with Universal or scuttled their plans to produce the game, Nintendo itself refused. On June 29, 1982, Universal sued Nintendo, aiming to stop production of the game and/or collect the profit of the game’s sale. Nintendo put up the typical defense, arguing that typical consumers would not see the oafish Donkey Kong as being confusingly similar to the menacing King Kong. But in case that didn’t work, Nintendo had another ace up their sleeve — Universal’s own arguments.

Universal’s King Kong movie debuted in 1976, but it wasn’t an original story. Rather, the movie was a remake of a movie with the same title made in 1933 by RKO General. The 1976 remake came with its own round of litigation, with many parties claiming to have at least partial rights over the name, characters, and plot of the movie. Universal, however, argued that no one did, and that the characters and plot were in the public domain. In the subsequent litigation with Nintendo, the court noted this inconsistency, using it as part of the basis for finding that Nintendo’s Donkey Kong game did not infringe upon Universal’s rights (if any) over King Kong. Nintendo prevailed, and, when Universal appealed, the next court admonished Universal for its inconsistent legal logic:

Universal’s conduct amounted to an abuse of judicial processes, and in that sense caused a larger harm to the public as a whole. Depending on the commercial results, Universal alternatively argued to the courts, first, that King Kong was part of the public domain, and then second, that King Kong was not part of the public domain, and that Universal possessed exclusive trademark rights in it. Universal’s assertions in court were based not on any good faith belief in their truth, but on the mistaken belief that it could use the courts to turn a profit.

Victory in hand, Nintendo was able to continue selling and marketing the Donkey Kong franchise. The fledgling video game capitalized on the success of this early triumph and became a gaming giant for decades to follow.

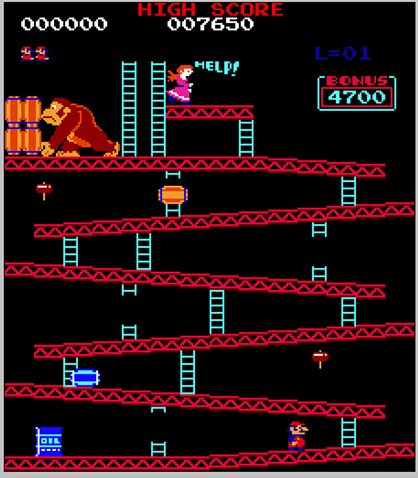

Bonus fact: The Jumpman character in Donkey Kong, seen above at the bottom right approaching a ladder, is now known as Mario, and easily recognizable as the main character of the Mario Bros. series of games. According to the book “Game Over,” which chronicles Nintendo’s emergence in the video game space, the character was named after Nintendo of America’s landlord at the time, Mario Segale. Segale, as the story goes, stormed into their offices one day demanding the overdue rent, and although Nintendo of America assuaged his fears, the outburst struck a chord with Donkey Kong’s game designers. Mario — Segale, that is — entered video game lore forevermore.

From the Archives: Cards, Love, and Mario: Nintendo’s non-video game origins.

Related: The two books mentioned above, “Power Up” (4.1 stars on 12 reviews) and “Game Over” (4.4 stars on 29 reviews).