When Astronauts Smuggled Mail into Space

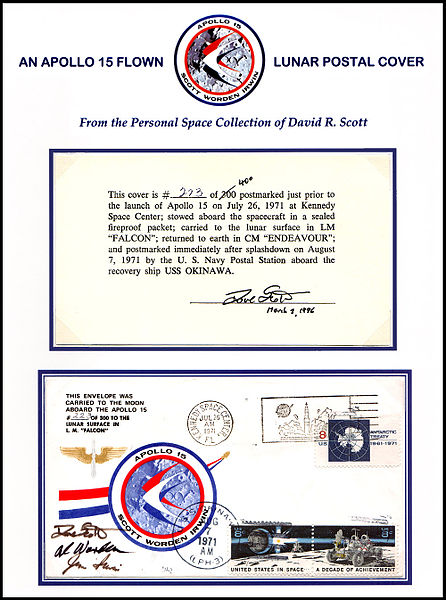

The image above (much larger version here) doesn’t look like much, but the item has been somewhere you haven’t — the moon. And there’s a very good chance that it shouldn’t have gone to the moon in the first place, and the fact that it did may have cost a couple of astronauts their jobs.

Apollo 15 launched from Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 26, 1971. Its lunar module landed on the moon’s surface four days later. The spacecraft carried three astronauts — Commander David Scott, Lunar Module Pilot James Irwin, and Command Module Pilot Alfred Worden — and 641 postage stamp covers, like the one seen above. Of those 641, 243 were authorized by NASA, a common practice for space missions at the time. (Most likely, 250 were authorized, but miscounting or damage to some covers reduced the authorized amount actually brought into space to 243.) The other 398 — 400, minus two which were damaged and therefore discarded — were smuggled aboard.

Where’d those extras come from? Before the Apollo 15 mission launch, a German stamp collector named Herman Sieger found out about the 243 NASA-authorized stamp covers and saw an opportunity. He connected with a German man (and naturalized American citizen) named Walter Eiermann, who was well-known in the area around Kennedy Space Center and had many contacts within NASA. Eiermann convinced the three astronauts to bring the extra 398 stamp covers aboard the flight with them, offering them $7,000 for their troubles, and gave them an extra 100 covers for their own purposes. Scott, who was traveling with an authorized cancellation stamp (for the 243 pre-approved covers), was to cancel the 398 contraband covers upon the mission’s return to Earth.

That part of the plan went without fail. The stamp covers made the trip without issue and were returned to Sieger, who had originally agreed to not sell any of the stamp covers until after the final Apollo mission came to a close (which, as it turns out, would be another year and a half or so). But Sieger failed to keep up that part of the bargain. As reported by the Spokesman-Review, he started to sell them almost immediately after, receiving $1,500 for each. In total, he earned roughly $300,000 (about $1.6 million in today’s dollars, accounting for inflation) — which, of course, caught the eye of critics far and wide. Even though what the astronauts did was not illegal, many observers objected, seeing the noble heroes become nothing more than profiteering opportunists. (Irwin, per some reports, would later say that he was simply trying to earn enough money to pay for his children’s college educations.) Congress ordered NASA to take action. NASA re-assigned the astronauts to non-flight roles, prompting their resignations, and confiscated their 100 remaining covers.

A few years later, in 1983, NASA and the U.S. Postal Service partnered to put 260,000 commemorative stamp covers on the STS-8 Challenger shuttle mission, hoping to raise money in the process. Noting that what they did was not very different, the Apollo 15 crew took legal action to regain their own stamp covers. According to Worden’s autobiography, they settled with NASA and the covers were returned. As recently as 2011, one of the covers (listed but not shown as item number 391 here) sold at auction for $15,000.

Bonus fact: Worden has two claims to fame due to the Apollo 15 mission. On August 5, 1971, he made the first walk in deep space, 196,000 miles from Earth; from that vantage point, he was able to see both the moon and Earth, as he told CNN. Second, Worden holds the record for the most isolated known person in human history. While Scott and Irwin were on the moon’s surface, Worden was in orbit above the moon, alone, and at one point was 2,235 miles away from the two men on the surface below. (That’s roughly the distance from Barcelona to Moscow.)

From the Archives: Lunar Art: Another thing the Apollo 15 crew smuggled aboard their spacecraft — but in this case, it’s something they left behind on the moon.

Related: “Falling to Earth,” Alfred Worden’s autobiography. 4.7 stars on nearly 50 reviews. Available on Kindle.