Swing Vote

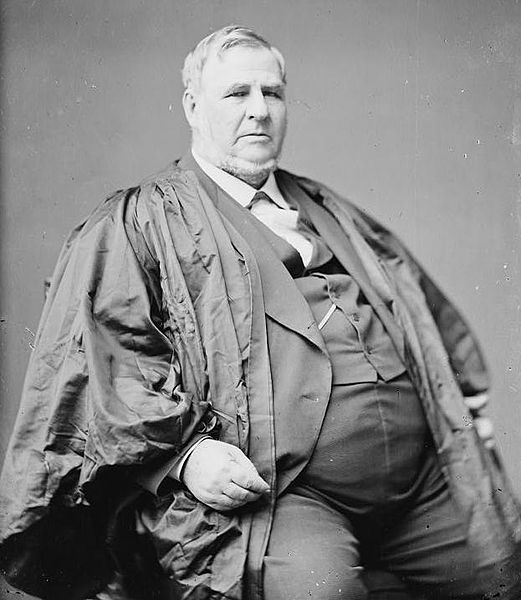

In 2008, Kevin Costner produced and starred in a movie titled Swing Vote. In the movie, Costner plays a New Mexico guy who, improbably and implausibly, ends up having the opportunity to cast the deciding ballot in the U.S. Presidential election. It’s a work of fiction, clearly, but over a century earlier, a man named David Davis (pictured above) was cast in a similar, non-fiction, role.

The 1876 U.S. Presidential election was one of the nation’s strangest. New York Governor Samuel Tilden, the Democratic candidate, received nearly 4.3 million votes nationwide, good enough for 51% of the popular vote. Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republican, received a hair over 4 million, accounting for just under 48%. (A handful of third party candidates made up the other one percent.) Tilden also looked like he’d win the Electoral College vote — the vote which, ultimately, is the one which matters in American Presidential elections — 196 to 173 — by virtue of the fact that he swept the southern states other than South Carolina . . . maybe.

In three southern states — South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida — both sides started to allege that the other engaged in voter intimidation and fraud. At the time, it was customary for parties to provide ballots with the preferred candidates’ names already written in. This was done, in part, because not all voters were literate, especially in the South. (One Wikipedia entry states that about 25% of whites in South Carolina were illiterate, as were 70% of blacks across the South.) The parties would put some sort of symbol on the ballots to express which party had issued them.

As recounted by the BBC, Hayes’s supporters alleged that Democrats in these three states had placed pictures of Abraham Lincoln on these pre-written ballots. Lincoln’s image, being an icon of the Republican Party, suggested to illiterate voters that they were voting Republican when they were, in fact, voting Democratic. Regardless of whether this concern was valid, the political realities took hold. The Republicans controlled the state government in all three states and discarded a number of ballots for Democratic candidates, including votes for Tilden. Suddenly, 19 Electoral votes were up for grabs. A 20th vote, from Oregon, would also join the controversy when one Hayes elector was deemed ineligible by the state’s Democratic governor, and was replaced by a Tilden supporter. With these 20 votes now unassigned, the nation had a major problem. Tilden had 184 votes to Hayes’ 165, but the Electoral College requires that a successful candidate receive a majority of the votes — or 185.< In order to solve the problem, the House of Representatives created an "Electoral Commission" -- five Representatives, five Senators, and five Supreme Court justices -- to decide how to allot the 20 outstanding votes. Originally, the Commission was to be comprised of seven Republicans, who were certain to support Hayes; seven Democrats, who similarly were certain to support Tilden; and one independent. That independent was Supreme Court Justice David Davis from Illinois, who, per one historian (as quoted by Wikipedia), was truly unaffiliated: “No one, perhaps not even Davis himself, knew which presidential candidate he preferred.” With little doubt, Davis was in the unique position of being able to decide, effectively on his own, who would be the next President of the United States.

But Davis’ apparent independence did not preclude the parties from continuing with politicking. Democrats controlled the Illinois state government, and, in an attempt to curry favor with Davis, elected him to the U.S. Senate. (Before the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913, Senators were not elected by voters directly, but rather by the state governments.) Davis, instead, used this election as a way to avoid being the swing vote to end all swing votes. He accepted the Senate seat and resigned from the Supreme Court, and, therefore, was ineligible to serve on the Commission.

With few choices remaining, the House placed Justice Joseph Philo Bradley — a Massachusetts Republican — on the Commission. Bradley, unsurprisingly, joined his fellow Republicans in awarding Hayes all 20 Electoral votes. Hayes became President, Davis became a one-term Senator, and Bradley received death threats. Tilden himself did not contest the outcome further. Per Wikipedia, he left politics altogether, stating: “I can retire to public life with the consciousness that I shall receive from posterity the credit of having been elected to the highest position in the gift of the people, without any of the cares and responsibilities of the office.”

Bonus fact: Tilden made a fortune for himself as a lawyer and investor, and died in 1886 with $7 million to his name — over $170 million in today’s dollars. He bequeathed the lion’s share of that to a trust, called the Tilden Trust, to create and maintain a library in New York City. The Tilden Trust helped fund the founding of the New York Public Library, whose landmark main branch has Tilden’s name engraved above its main entrance.

From the Archives: Vice President . . . Who?: Hayes’ victory resulted in William Wheeler becoming Vice President, and Hayes figuring out who Wheeler was.

Related: “Fraud of the Century: Rutherford B. Hayes, Samuel Tilden, and the Stolen Election of 1876” by Roy Morris, Jr. Originally published in 2004, it is one of the few books on the controversial election. 3.6 stars on 25 reviews, with a handful of negative ones concerned that the author is one-sided.

Leave a comment