Taking “One Person, One Vote” Literally — and Accidentally

Maintaining and improving on infrastructure can be expensive. Paving roads, cleaning sidewalks, and the like all come at a cost, and in many areas, we expect everyone to pitch in. There are lots of different ways to collect the money for these activities, the pros and cons of which won’t be debated here. But let’s highlight one, called a business or community improvement district (commonly abbreviated to BID or CID). These areas are, often, subsections of existing cities and towns which pool their resources for the collective good. Manhattan’s Times Square, for example, has the Times Square Alliance, a BID which not only keeps the area somewhat clean, but also actively markets the neighborhood to tourists. Most of the Times Square Alliance’s money comes from local businesses, who are the major beneficiary of the Alliance’s work.

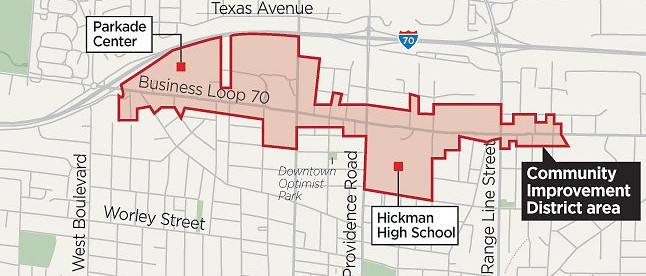

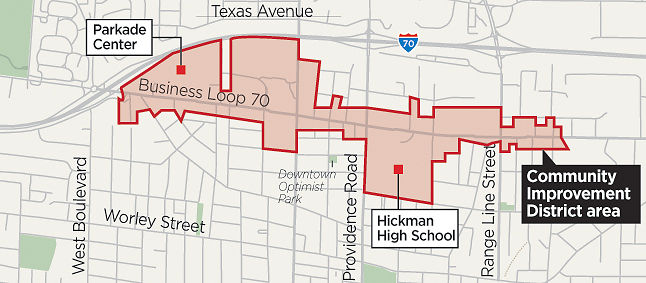

In April of 2015, the city council of Columbia, Missouri, decided that part of its downtown area needed a similar program. The council voted to create the “Business Loop 70 Community Improvement District,” which is comprised of a commercial area just to the south of where Interstate 70 bisects the town. But the CID map is, well, a little weird looking — it juts out in some places and carves out others. Let’s take a look:

The reason for the odd shape is simple. Missouri law empowers CIDs to impose taxes and assessments as needed to fund their improvements — the money has to come from somewhere, after all. And all the CID needs to get a tax in place is the permission of the voters who live within the CID. Given that these are, by definition, commercially zoned, that may mean there are very few voters in the area — and, in some cases, none at all. Missouri law accounts for that “no voters” possibility by adding a fall-back plan: if there are no residents in the CID, property owners get to vote instead. Columbia saw this fallback as an opportunity. The CID borders were drawn to ensure that no one lived within its boundaries, thereby allowing the commercial landlords the right to vote. The plan was to enact a 0.5% sales tax on all purchases made in the CID, which would have raised nearly $250,000 annually for the neighborhood’s upkeep and to pay down some debt incurred by the CID as drawn previously.

But Columbia made a mistake — they drew the lines wrong.

Initially, the only person to notice was a college student named Jen Henderson. That wouldn’t be a big deal except for the fact that Henderson lived within the CID, and she was a registered voter. Oh, and she didn’t believe the sales tax was a good way for the CID to raise money for its needs. As she explained to the Columbia Daily Tribune, the local residents who shopped at the CID were often rather poor, and “taxing their food is kind of sad, especially when [the CEO of the CID] is going to be making like $70,000 a year off of this whole deal. These people make a quarter of that.” And as the only registered voter in the area, she was the one person whose vote would matter.

But she was never able to exercise that supreme power, even momentarily. Whether Henderson’s take on economic policy is sensible can be left for another day. But the CID didn’t like it, that’s for sure. They tried to get her to unregister to vote, but she didn’t, and the ballot measure was doomed to fail. But the CID wasn’t done. In August of 2015, just days before the vote was to occur, the CID — which, by law, was not allowed to campaign for Henderson’s support — decided to postpone the ballot measure altogether.

That turned out to be an effective solution; those who designed the CID realized that they drew the lines even worse than they thought, and Henderson wasn’t alone — as many as 14 other people also lived within the CID’s boundaries. That December, the CID rescheduled the vote and sent ballots to all 15 people. Seven voters returned ballots and the CID’s tax passed, 4-3. Henderson filed suit, hoping to vitiate the election results, but she ultimately lost.

Bonus fact: In 1994, the Ku Klux Klan tried to get its name on a stretch of a Missouri highway — Interstate 55 — in the state’s “adopt a highway” program. Missouri refused but the Klan sued and, ultimately, won. (It took a few years.) The state, though, had another solution: it named the highway after civil rights icon Rosa Parks. As a state spokesperson told the Chicago Tribune, this brought some poetic justice to the situation, noting that “the governor appreciates the irony of the KKK picking up trash along the Rosa Parks Highway.”

From the Archives: Swing Vote: The one person who controlled a Presidential election.

Related: An electronic voting system for you and 50 friends. Good for corporate events more than anything else.