The Balloon Expedition to the North Pole That Was a Bust

The North Pole isn’t a good place to visit — it’s cold, hard to get to, and there’s not much there. But the challenge of reaching the northernmost point on the planet, well, for some, that’s reason enough to venture there — or, at least to try. It’s not entirely clear who was the first to reach the North Pole — being there isn’t the easiest thing to prove — but credit is generally given to American explorer Robert Peary, who claimed to reach the Pole on April 6, 1909. Whether he actually made it there is often debated., but what isn’t debated is whether he was the first to try. He wasn’t, and some explorers were very creative.

In one case, maybe it was a bit too creative.

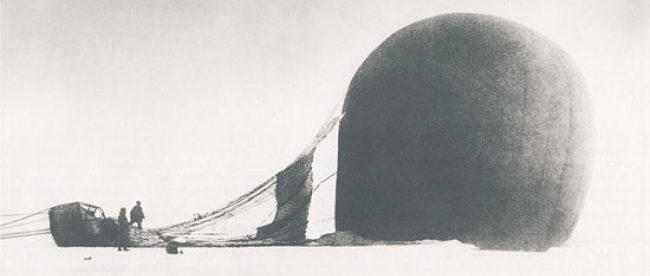

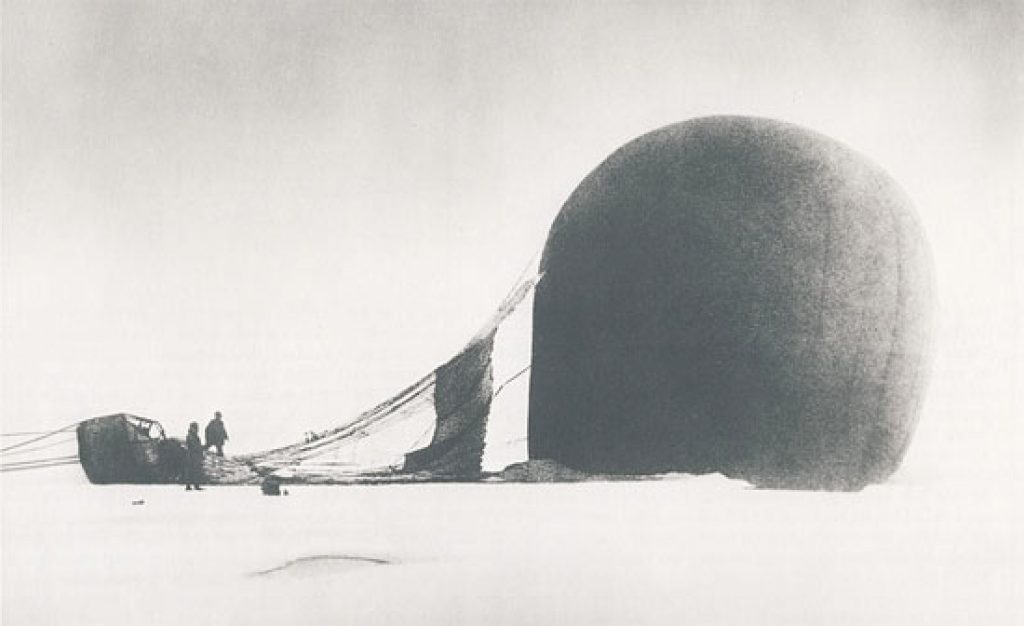

That, above, was the brainchild of a Swedish explorer named Salomon August (S.A.) Andrée. As the 1800s approached a close, many adventurers headed north, hoping to be the first one to go as north as one can go. Andrée was among them, but he wasn’t keen on taking a ship to the north — everyone else had failed using that strategy. So he — more scientist than outdoorsman — found another way: a hydrogen balloon.

The idea was simple: Fly to the top of the Earth. Or, more correctly, float. Why go through the ice when you can go above it?

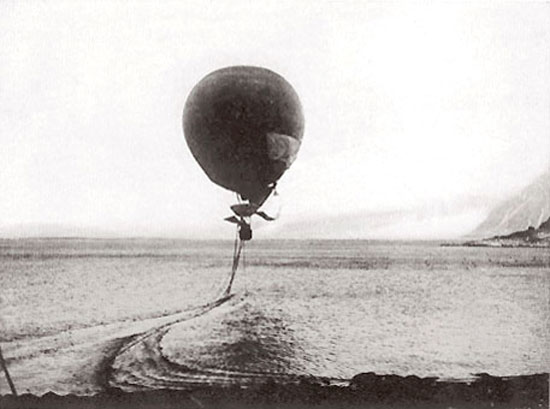

That sounds like a solid plan, but there was a problem: steering. Ballooning tech at the time simply didn’t have a way to guide your balloon in the direction you wanted to go. Andrée’s solution to this detail, as seen above, was to float not too far above the ground and drag some ropes to the surface below. The ropes, in theory, would act as a steering system — he could pull ropes or drop new ones to take advantage of the friction at the contact point (or the water currents when over water), guiding his balloon this way and that. In 1897, with the backing of the King of Sweden, Andrée and team christened their balloon “the Eagle” and made their way skyward.

It didn’t work. Mental Floss explains:

Astute readers have probably realized that they’ve never seen a balloon that is steered via drag ropes. There’s a good reason why you haven’t; the method is wildly ineffective. The three drag ropes on the Eagle didn’t even work long enough for the balloon to fully clear its launch area. The balloon drifted into a downward draft almost immediately after taking off and nearly dipped into the icy water. Andree and the crew had to dump sand overboard just to keep the balloon afloat.

The balloon crashed, as seen below, only about 65 hours after it departed. Without the ropes to guide it — and to weigh it down — the aircraft floated to higher than intended altitudes and ultimately, sprung a leak. They landed safely but no one knew where they were, nor to look for them; they survived for about two or three months until finally succumbing to the elements.

How do we know? While Andrée and his team drifted over into the Arctic and were never seen again, their memories survived. Thirty-three years after the balloon expedition went bust, a group of seal hunters and geologists made their way to Kvitoya, an island in the Arctic, but not all that close to the North Pole. (Here’s a map.) What they found there was more than what they bargained for. There, they discovered the remains of Andrée’s expedition within the ruins of their final camp — and, as the New York Times reported, “diaries and tins of film” which recounted their final days. From this, we learned the fate of the expedition, and get to see some of the aftermath with our own eyes (through their camera’s lens).

More photos from the recovered tins can be found at Atlas Obscura.

From the Archives: Here Comes Santa Claus: Why the U.S. military tracks Santa’s movements every Christmas Eve.