The Check Republic

Checks (“cheques” in many parts of the English-speaking world) are, basically, IOUs. The person writing the check promises to pay the check’s recipient at some point in the very near future. The check writer isn’t even part of the transaction at that point — the writer’s bank is instructed, literally, to “pay” the amount specified “to the order of” the person to whom the check is made out. The bank plays a critical role in the transaction beyond the delivery of cash, too — it helps ensure that the check writer is good for the debt now owed, by imposing bad check and overdraft fees on those who write checks larger than their accounts can handle. These and other assurances help keep the financial system moving, even if checks aren’t cashed or don’t clear immediately.

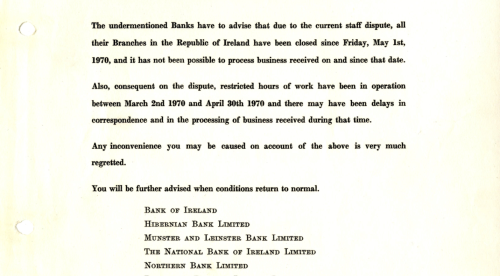

For checks to work, that level of trust is necessary — but it doesn’t need to come from the banking system. This was certainly the case in Ireland in 1970, when for much of the year, there wasn’t much of a banking system of which to speak.

From 1966 through 1976, the Irish banking system was a muddled mess. Bankers were regularly unhappy with the regulatory climate and the industry, as a whole, shut down three different times. The longest of these bankers strikes was a six-month work stoppage starting on May 1, 1970. An already weak Irish economy was poised for disaster — savings were locked up, the money supply shrunk by as much as 85%, and importantly for our purposes, check clearing disappeared. That is, if you wrote someone a check on April 30, 1970, normally they’d go and cash it the next day — but with the banks now closed, they couldn’t do that. And with no obvious end date to the strike, you could be holding that uncashable check for a long, long time.

One would expect the bank strike, therefore, to make checks basically worthless. But the exact opposite happened. Check writing increased as these IOUs became a de facto type of currency.

Part of that happened out of necessity — the massively-decreased money supply meant there simply wasn’t enough cash floating around to keep the economy moving forward, so something had to step in to fill the void. But as checks have no intrinsic value — and each one may result in an unpaid debt down the road — another factor was necessary to get this to happen. Those who received a check from another needed to have confidence that the person who originally wrote the check had the ability to pay the amount stated (or would by the time the banking industry came back to work). In short, the Irish economy needed a system which reliably measured the financial reputation of individuals.

And it had one — thanks to the relatively high number of pubs in Ireland and the relative loyalty of pub-goers.

In an academic paper titled “Money in an Economy without Banks: The Case of Ireland,” a researcher named Antoin E. Murphy examined the issue. His finding was that local stores and pubs really, really knew their customers, and as a result, saved the day:

[M]anagers of these retail outlets and public houses had a high degree of information about their customers—one does not after all serve drink to someone for years without discovering something of his liquid resources. This information enabled them to provide commodities and currency for their customers against undated trade credit. Public houses and shops emerged as a substitute banking system.

The system wasn’t as good as the normal banking system, of course — this article has a story about one publican who lost untold amounts of money when he stored his checks in the chimney, but forgot to tell his wife not to light a fire there, for example. (That article also has a great story about a guy who bought a horse using a bad check, only to have that horse earn back plenty in race winnings before the check had to clear. So for some, this alt-banking system turned into a windfall.) So when the banks reopened on November 17, 1970, everything began to return to how things were beforehand, and the parallel banking system dissipated into history.

Bonus Fact: One weird side-effect to the Irish checks-as-currency economy of 1970? A shortage of checks. Official checks had a government stamp on them, signifying that the tax on the check was paid, but also providing an air of legitimacy to the document. As official checks ran low, postage stamps acted as a suitable alternative — and could be used to turn virtually any piece of paper into a viable check. As the Financial Times reported, “in pubs, by now the principal clearing houses, the insides of cigarette packets suddenly became bills of exchange, as patrons [removed the cigarettes], scrawled a cheque, stuck on a stamp and handed it across the counter to the acquiescent publican.”

From the Archives: Feed the Pig: Where piggy banks come from.

Take the Quiz: Name these countries that aren’t Ireland (even though the clues apply to Ireland also).

Related: “Anglo Republic: Inside the bank that broke Ireland,” an account of the more recent banking woes Ireland has faced. More than 500 reviews averaging 4.5 stars.