The Crime Witness Who Missed the Point

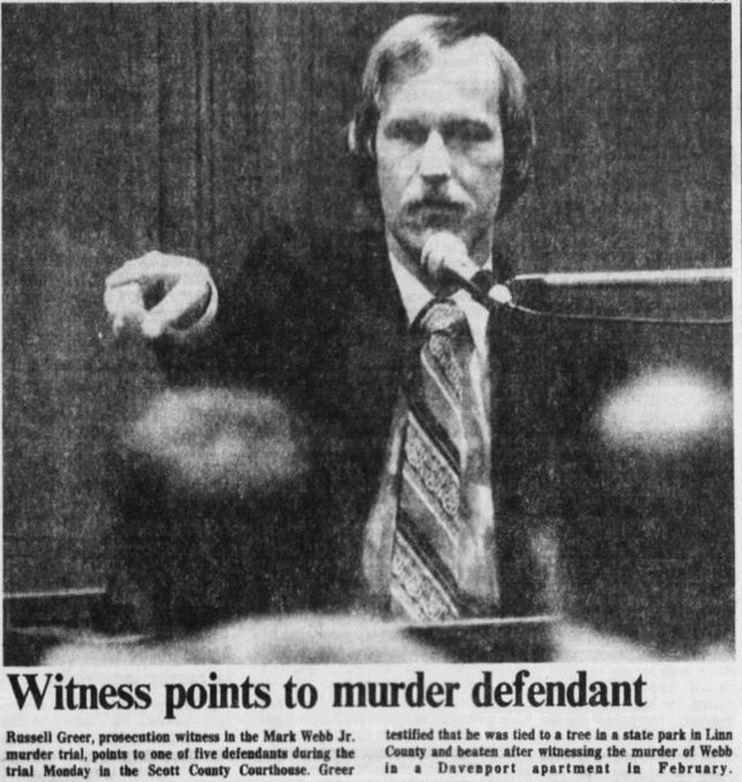

The image above, well, it’s something I just pulled off the Internet. It tells a very familiar story, though — familiar enough to those of us who have watched legal dramas on TV, anyway. Typically, the defendant is sitting next to his or her lawyer. A witness to a crime is asked to identify the person he or she saw committing the alleged crime, and the witness replies by pointing to the defendant. It’s a very basic way for the prosecution to establish that the person being accused of a crime is the person that the witness saw. And yes, it really happens in real life, just like it does on TV (but minus any background music).

The whole maneuver seems foolish, though; the defendant is typically the person sitting at the defense table; it’s not like the witness is picking the person out of a crowd. Sometimes, though, things go wrong. In 1987, for example, a witness in an arson trial was asked to point to the man she saw running from a burning building. She obliged by pointing to one of the two men seated at the defense table — but she picked the wrong one. As the Chicago Tribune reported, “The woman pointed confidently and identified the defendant`s attorney, Stephen Knorr, who was sitting next to the defendant.”

But mistakes like that aside, it’s generally rather predictable what is going to happen: the witness is going to point to the right person seated at that table. And that gave a lawyer named David Sotomayor (no relation to the Supreme Court justice) an idea.

The year was 1994. Sotomayor was representing a man named Christopher Simac, who was charged with driving with a revoked license. It was an open-and-shut case. Simac was, allegedly, involved in a traffic accident, and when a local police officer named Ronald LaMorte arrived on the scene. LaMorte demanded that Simac hand over his license. Simac couldn’t comply because the license had been revoked. At trial, all LaMorte had to do was tell that story and then identify Simac. And that’s what he did — or tried to do, at least. When on the witness stand, LaMorte recounted the facts of the day without a problem. Then the officer was asked to point to the man he saw on the day of the accident, and he did what almost anyone would do — he pointed to the guy sitting next to the defense attorney, Sotomayor.

Sotomayor responded by calling that man to the witness stand and asking him what his name was. And the man didn’t say “Christopher Simac.” He said, under oath, that his name was “David P. Armanentos.”

In that courtroom, at least, there was no requirement that the defendant sit in the chair that defendants typically occupy. In a last-minute effort to get his client acquitted, Sotomayor decided to use this to his advantage. Simac, it turned out, looked a lot like Armanentos, and was a temporary law clerk who was working for Sotomayor. So he had them dress somewhat similarly — they both donned striped shirts and wore glasses — but switch positions. Armanentos sat where the defendant typically would while Simac remained in the gallery, in view of the witness stand but not where the officer would normally focus his attention.

The ruse worked; as the New York Times reported, “the good news for the defense was that Associate Judge Donald J. Hennessy gave a directed verdict of not guilty.” as the prosecution failed to establish that Simac was the culprit. But Sotomayor’s victory came at a price. Judge Hennessy held Sotomayor in criminal contempt for “conduct calculated to embarrass, hinder or obstruct a court in its administration of justice or to derogate from its authority or dignity” and smacked him with a $500 fine.

Sotomayor appealed the fine — an appeal which made its way to the state Supreme Court. An appellate court reduced the fine to $100 but, by a 4-3 vote, the Supremes upheld the criminal contempt order. Sotomayor was, however, allowed to keep his law license.

Bonus fact: Another strategy to win your case? Show up in costume. In 1978, a Disneyland performer playing Winnie the Pooh was accused of slapping a child so hard that he caused her recurring headaches and possible brain damage. When the defendant was called to the stand, per Wikipedia, he did in his Pooh costume, “responded to questions while on the witness stand as Pooh would, including dancing a jig.” In doing so, it became clear that “the costume’s arms were too low to the ground to slap a girl of the victim’s height,” making it impossible for him to have caused the damage he allegedly inflicted. The jury found in his favor in under a half-hour.

From the Archives: What to Call Witnesses, According to the Supreme Court: Not really related to the above, but it’s about witnesses in court cases, so close enough.