The First Female Senator (For a Day)

On June 4, 1919, the United States Senate passed what would become the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote. As the amendment had already passed the House of Representatives that May, it then went to the states for ratification. A total of 36 of the then-48 states had to vote in favor; that happened on August 18, 1920, when Tennessee — barely — became the 36th state to ratify the Amendment. As the year-plus gap suggests, the battle over ratification was a long and difficult one. And in a weird, backward way, it gave America its first female U.S. Senator.

But only for a day.

The proposed 19th Amendment wasn’t popular in the southern states — eight such states explicitly voted to reject it, at least at first. Georgia was the first to do so. On July 24, 1919, the Georgia House of Representatives overwhelmingly torpedoed the effort by a vote of 118 against and only 29 in favor. From a big picture perspective, that didn’t matter much; the Amendment ultimately made its way into the Constitution anyway. But for Thomas W. Hardwick, it proved to be a strange hurdle.

In 1919, Hardwick was between jobs. That March, he finished up a term as a U.S. Senator from Georgia, having been defeated in the Democratic primary the previous year. A return to public service was in the near future, though. In June of 1921, Hardwick was elected the 63rd Governor of Georgia. But the Senate was where Hardwick really wished to be. And when Senator Thomas E. Watson died on September 26, 1922, a seat opened up. Hardwick began his candidacy for the seat nearly immediately, with a special election to fill it scheduled for that November.

In general in the U.S., when a death or resignation in the Senate results in an open Senate seat, the governor of that state appoints a person to fill that seat until the special election. The death of Senator Watson was not an exception; Governor Hardwick had the power to appoint someone to fill Watson’s now-empty seat. But there was little need to do so — the Senate was in recess when Watson died, and wouldn’t reconvene until November 21st, after Georgia’s special election. Whomever Hardwick appointed would never actually serve in the Senate — and this provided him with an unusual opportunity.

In the debates around women’s suffrage, Hardwick came out against the 19th Amendment. By the time that 1922 Senate election were to come around, though, the Amendment had become part of the Constitution. Women, therefore, were eligible to vote — and Hardwick understandably feared that many wouldn’t take kindly to his anti-suffragist efforts. But one well-known suffragist, an 87-year-old named Rebecca Latimer Felton, gave him a way out. Felton, the widow of a former House member from Georgia, had endorsed Hardwick for governor in the 1920 campaign “despite his hostility to woman suffrage and prohibition after he announced his opposition to the League of Nations,” according to the Senate’s website. While entirely ceremonial — no one expected Felton to actually serve as a Senator — Hardwick appointed her to Watson’s open seat.

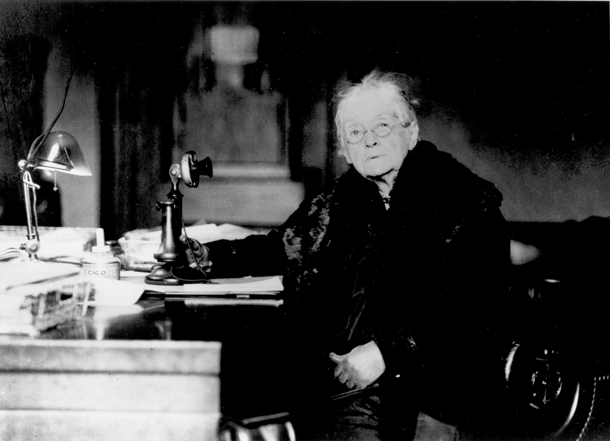

Hardwick’s ploy to win over women voters and pro-suffrage men, though, didn’t work. He lost the election to Walter F. George, who would end up serving in the Senate for more than three decades. But Felton convinced Geroge to not start his new role right away. Instead of obtaining his Senate credentials on November 21, as he was entitled, George did so the next day. Felton, as seen above at her Senate desk, took the seat for most of the November 22nd as George waited to be sworn in. In her one and only Senate address, available here (pdf), she extolled the impact women of the future would have on Congress: “you will get ability, you will get integrity of purpose, you will get exalted patriotism, and you will get unstinted usefulness.”

Bonus fact: Felton was a historic first and a historic last. Felton was 30 years old in 1865, which is when the 13th Amendment — the one that outlawed slavery — was ratified. Felton and her husband owned slaves prior to the Civil War; she was the last member of Congress to have also been a slave owner. And slave ownership was consistent with many of Felton’s other beliefs. Per her Senate biography, Felton was “an outspoken white supremacist and advocate of segregation” — and violently so. As the Lily (a publication of the Washington Post) notes, “in what was arguably her most famous speech in 1897, Felton advocated for the lynching of black men. ‘”If it needs lynching to protect women’s dearest possession from the ravening human beasts — then I say lynch, a thousand a week, if necessary,'”

From the Archives: Fighting for the Right to Vote: The bonus fact is one of the most surprising things I’ve seen.