The Genie’s Art

In 1992, Disney released Aladdin, an animated adaptation (to use the term “adaptation” very loosely) of the Arabian Nights folk tale of the same name. The movie was a huge success, garnering two Academy Awards among dozens of honors and accolades — and making bucket loads of money. The film earned more than $500 million at the box office on a $26 million budget, and a lot of the success had to do with the genius of the voice of the genie, Robin Williams. Williams’s performance thrilled audiences and critics alike. Two decades later, after Williams’ untimely death, the Los Angeles Times recounted the impact Williams had on the film:

Reviewing the film in 1992, [Los Angeles] Times critic Kenneth Turan wrote of Williams’ Genie that, “animation has never had a human partner who so pushed it to its comic limits,” while the New York Times’ Janet Maslin called him a “dizzying, elastic miracle.”

And to Disney’s credit, they wanted Williams from day one — and made an extraordinary effort to recruit him into the role. Per that same Times article, the studio instructed animator Eric Goldberg to watch Williams’ standup routines and animate the genie character performing them. Goldberg delivered, the studio showed it to Williams, and the comic signed on to play the role. And he did it at a discount, too — he received only $75,000 for the role.

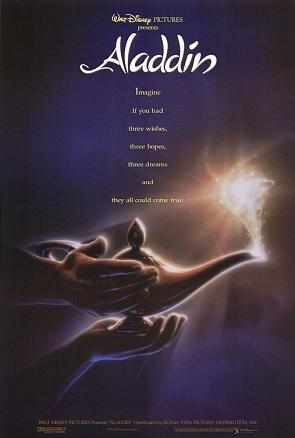

That amount came with some conditions, though. Williams had another movie coming out that season,Toys, and wanted to do what he could to ensure Toys‘ success. So he insisted that Disney not use his name in marketing materials and that his character, the Genie, not be used prominently in posters (taking up no more than 25%) and other promotional material. Further, Williams insisted that his voice not be used to market toys and the like, as he wanted to make movies, not merchandise. The image above shows an example of how Disney delivered on those promises — that’s the original promotional poster.

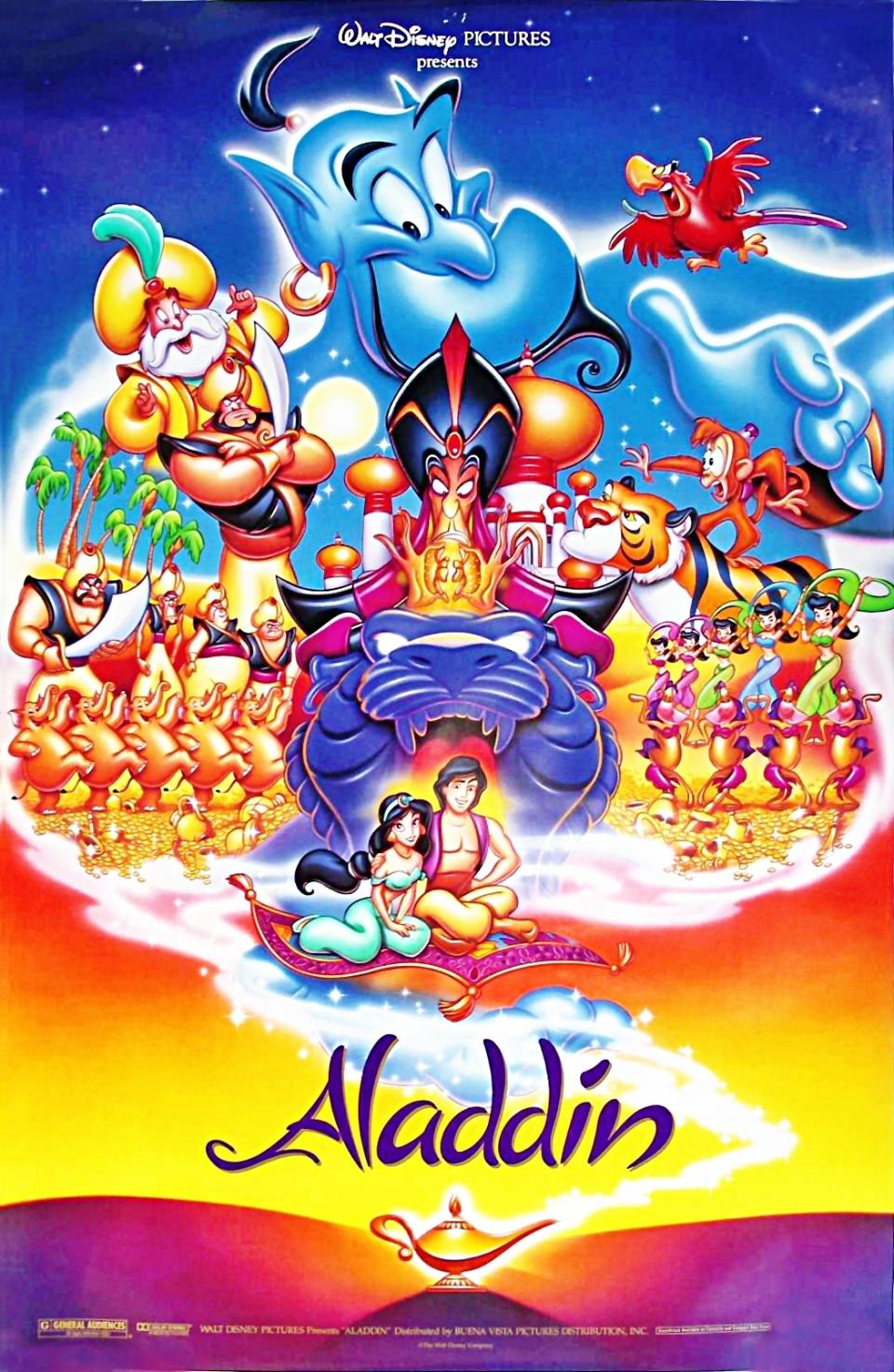

And then this happened.

That’s a pretty big Genie. Much bigger than Williams had agreed to.

The agreement was a handshake one, not put to paper or otherwise created in any legally-binding way. Disney went back on its word, using the Genie as a central point to its marketing efforts. To make matters worse, Disney used Williams’ voice in toy promos as well. In another Los Angeles Times article, the paper reported that Williams wasn’t too happy about it:

“You realize now when you work for Disney why the mouse has only four fingers–because he can’t pick up a check,” Williams told interviewer Gene Shalit [on NBC’s the Today Show]. Williams makes a similar comment in the Nov. 22 issue of New York magazine.”We had a deal,” the actor said on the NBC show. “The one thing I said was I will do the voice. I’m doing it basically because I want to be part of this animation tradition. I want something for my children. One deal is, I just don’t want to sell anything–as in Burger King, as in toys, as in stuff.”

Williams said Disney executives agreed to honor his wishes, “Then all of a sudden, they release an advertisement–one part was the movie, the second part was where they used the movie to sell stuff. Not only did they use my voice, they took a character I did and overdubbed it to sell stuff. That was the one thing I said: ‘I don’t do that.’ That was the one thing where they crossed the line.”

Williams vowed to never work for Disney again. Disney, in 1993, sent Williams a Picasso — valued at $1 million at the time — in hopes of buying back his love. It didn’t work, and over the next few years, Disney would continue with the Aladdin franchise without Williams’ voice. There was an animated TV series in 1994-1995 and the first direct-to-video Aladdin sequel, The Return of Jafar, in 1994. Dan Castellaneta, who is best known for voicing Homer Simpson, performed the Genie for the both of those. Castellaneta was also tabbed to do the Genie’s voice as well as for another direct-to-video movie in the Aladdin series, Aladdin and the King of Thieves, which was scheduled for a 1996 release.

But Williams eventually relented. Jeffrey Katzenberg, who ran Walt Disney Studios during the kerfuffle, left on bad terms in 1994. He was replaced by Joe Roth, who was in charge of 20th Century Fox previously. Williams and Roth were on excellent terms because the latter greenlit Mrs. Doubtfire toward the end of this tenure at Fox. Roth had Disney issue a public apology to Williams who, in turn, accepted it. The relationship now mended, Williams ending up recording the voice of the Genie for the Aladdin and the King of Thieves sequel.

And he kept the Picasso.

Bonus Fact: In the original Aladdin story — the Arabian Nights folk tale version — Aladdin isn’t from the Middle East. He’s Chinese.

From the Archives: And the Oscar Doesn’t Go To: What may happen when you really don’t like the movie you made.

Related: Aladdin and the King of Thieves. While often panned by critics, it seems to do the job: 4.4 stars on nearly 100 reviews.