The History of Fondue and the Cheese Cartel that Popularized It

Take a mix of cheeses — gruyere as one, if you’re going authentic — and toss it into an earthenware pot. Add in some wine and garlic if you’d like, and place the pot over some Sterno or other portable heat source. While the cheese melts, find yourself some stale bread and some long forks or skewers. Once the pot of cheese begins to bubble, place some bread on the end of that fork, dip the bread into the cheese mix, and let it cool just a bit. Then pop the cheese-covered bread into your mouth, grab another piece of bread, and repeat until the cheese (or bread if you’re doing it wrong) is all gone.

Congratulations, you’ve just eaten fondue. If you liked it, you can thank a century-old cheese cartel.

Fondue has a long and opaque history, at least until the mid-1900s. As noted by the BBC, Homer — the Greek poet — made reference to “a mixture of goat’s cheese, wine and flour” in the Iliad nearly 3,000 years ago. The first modern recipe emerged in a 1699 in a cookbook from Zurich which, according to Wikipedia, “call[ed] for grated or cut-up cheese to be melted with wine, and for bread to be dipped in it” but never used the word “fondue.” Other than that, though, mentions of the recipe were intermittent. Up until about 1930, the dish remained regional, even inside of Switzerland.

That changed, in part, due to World War I. The First World War ravaged the European countryside and, in particular, France and Germany. But Switzerland, which remained neutral throughout the war, was left relatively unscathed — and so did its cows. During and after the war, Switzerland had the ability to produce a lot more cheese than Europe could purchase, and pre-World War II tariffs and trade restrictions made the problem even worse. So a group of Swiss cheese makers came together to create something called Schweizer Käseunion AG, or the Swiss Cheese Union. Starting in 1914, the cartel — with the government’s blessing and support — controlled everything relating to cheese in the country: how much could be produced, what prices cheese makers could charge, and even restricting the types of cheeses that could be made. Understandably, these actions made them unpopular. In a recent (April 2015) NPR story, a reporter asked restaurant managers about the Swiss Cheese Union only to find that the managers disavowed any knowledge of the Schweizer Käseunion at all. One expert the reporter spoke to said that was because the people interviewed likely saw themselves as “survivors” of the cartel.

The abuse of power by the Union was mostly successful, though. But industries have to grow to survive, and Swiss cheeses aren’t immune to this need. By the 1930s, there was still a lot of cheese making capacity and a lot of upset cheese makers who were being told to stop producing it. So the Swiss Cheese Union found a way to do more without asking the cheese makers to do even less: the cartel went into marketing.

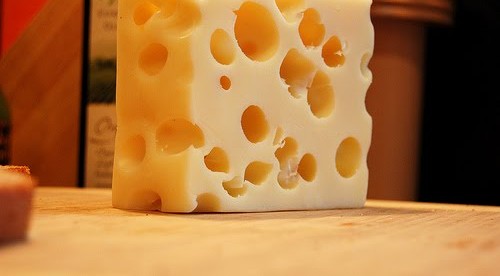

Having already limited the supply of Swiss cheeses, the Union looked at ways of increasing demand. One of the reasons that Americans refer to Emmental — the hard cheese with holes, as seen here — as “swiss cheese” is because the Union focused many of its early marketing efforts on popularizing that variety. But its biggest success came from the 1930s to the 1970s, when the cartel popularized fondue. Before the Union got in the mix, fondue wasn’t well known in most of Switzerland and, for that matter, was unheard of internationally. It was, however, common in some parts of the Swiss Alps, perhaps because the people there happened to have a lot of cheese and had a hard time keeping their bread fresh due to the climate conditions.

The Swiss Cheese Union decided that this was the product they had been looking for — think about the extraordinary amount of cheese that goes into a fondue pot. According to a Wall Street Journal report, the Union began mailing fondue recipes to households across Switzerland. An advertising blitz, per NPR’s Planet Money, featured attractive Swiss partygoers gathered around the fondue pot while touting the vat of melted fat as a healthy choice for a snack. Over the decades, fondue became increasingly popular — the Union’s ploy had worked. The dish’s popularity has waned since, but not before much of the world tried it. Fondue is still very common in restaurants throughout Switzerland, and one can still find fondue sets in most cooking stories around the globe.

As for the Swiss Cheese Union, it did not last the century. In part due to corruption among its officials (with some ending up in prison), the Schweizer Käseunion folded in 1999.

Bonus Fact: The holes in Emmental cheese is caused by a gas emitted by a bacteria — gas which doesn’t escape during the cheese making process. Wikipedia explains: “In the late stage of cheese production, P. freudenreichii consumes the lactic acid excreted by the other bacteria, and releases carbon dioxide gas, which slowly forms the bubbles that make holes. Failure to remove CO2 bubbles during production, due to inconsistent pressing, results in the large holes (‘eyes’) characteristic of this cheese.”

Bonus Fact: The holes in Emmental cheese is caused by a gas emitted by a bacteria — gas which doesn’t escape during the cheese making process. Wikipedia explains: “In the late stage of cheese production, P. freudenreichii consumes the lactic acid excreted by the other bacteria, and releases carbon dioxide gas, which slowly forms the bubbles that make holes. Failure to remove CO2 bubbles during production, due to inconsistent pressing, results in the large holes (‘eyes’) characteristic of this cheese.”

Take the Quiz: Cheese or Crackers: There are 23 items listed below. Twenty are types of cheese. The other three are types of crackers. Can you pick the 20 cheeses with choosing a cracker first?

From the Archives: This Cheese Stands Alone: The very rare, very expensive moose cheese.

Related: A pretty nice fondue set. Cheese, bread, Sterno, and overbearing cartel boss not included.