The Masterpiece Hidden in Plain Sight

You can be forgiven if you’ve never played the board game “Masterpiece,” pictured above. Originally published in 1970 by Parker Brothers, the game never reached the popularity of other mainstream Parker Brothers games like Boggle, Risk, Sorry!, or Trivial Pursuit, and as niche games go, it gets mediocre reviews from dedicated board gamers.

But Masterpiece was successful enough to warrant three printings — in 1970, 1976, and most recently in 1996 — and led to the discovery a million dollar masterpiece.

The board game Masterpiece is centered around famous works of art. Players bid on and trade pictures of masterpieces (hence the name) by Renoir, Van Gogh, and others, representing either the actual works of art or, perhaps, forgeries thereof. The player to amass the most valuable portfolio of cash and “real” art wins. The actual game mechanics aren’t all that important, though, at least not for those of us not playing the game right now. What’s important is that Masterpiece, the game, uses images of real masterpieces. If you play the game often enough, you’re likely to develop a mental catalog of the works depicted.

Or, maybe you just get lucky.

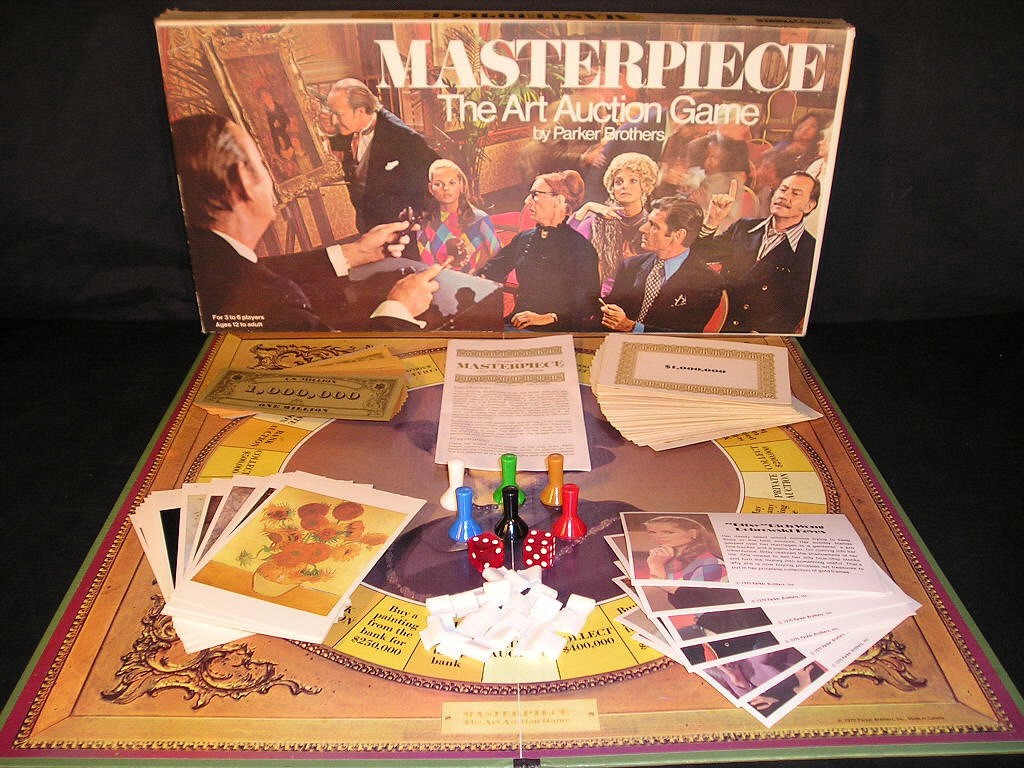

In January of 1999, a 30-something Indiana man was playing the game at home. During the game, a work by 19th-century American painter Martin Johnson Heade came across the board. It was one of Heade’s later works — a painting of magnolia like the one seen above. And the magnolia painting wasn’t the only one in the Indiana man’s home that evening. As the New York Times reported, there was another just a room away, covering a hole in the wall.

The similarities between the game piece and the actual painting piqued the owner’s curiosity, so he did a little research and learned that Heade’s later works included a number of magnolias-on-velvet paintings. In hopes that the one hanging on his wall was a Heade original, the Indiana man — who has done a great job of remaining otherwise anonymous — contacted a gallery that had a deep familiarity with Heade’s work. His instincts were confirmed. The man found out that his impulse buy which he got for “next to nothing” was, in fact, worth a lot more than “nothing.” That June, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston bought it for $1.25 million.

This isn’t the only one of Heade’s magnolias floating around out there, either. Heade wasn’t very parochial about where they ended up — he wasn’t only offering them for sale at high-end galleries. As a result, one Harvard University curator explains (via Wikipedia), “[Meade’s] paintings continue to turn up in garage sales and other unlikely places all over the country.” So you, too, may find some benefit in picking up a copy of Masterpiece — it may help you spot a million dollar prize in the future.

Bonus fact: In 1972, Parker Brothers came out with the dice game Boggle, which if you’re unfamiliar with involves a 4×4 grid of letter-laden dice, shaken to randomize what’s showing on top. The object is to identify words spelled out by those dice. (Wikipedia has more, here, if you’ve never seen the game, but it’s pretty common so I’m assuming you’ve played it.) In 1986, Boggle underwent a minor redesign; as part of the change, the letter K only appeared on one cube, down from two cubes previously. But more interestingly, the game designers also changed on which die that letter K appeared. In this new version, the one die with the K now also had an A, two Fs, a P, and an S on those other five sides. Why bother? Parker Brothers’ never admitted to it, but this was probably a creative way of making the game family-friendly. Those Fs were the only two Fs in the game; this new AFFKPS die made it impossible for an F and a K to appear in the same word.

From the Archives: The Time Championship Scrabble Almost Led to a Strip Search: Board games gone wild. Or, at least, gone controversial.

Related: If you own a copy of the 1970 version of Masterpiece, great news! It’s out of print and is therefore pretty expensive.