The Queen’s Flesh and Blood Insurance Policy

Every May or June — depending on whether the United Kingdom is holding Parliamentary elections that year — both houses of Parliament assemble to be addressed by the reigning monarch. The event is rife with pomp and circumstance, as one would expect from a regal tradition which dates back to the 1500s. The royal regalia — the crown — arrives at Parliament under guard. Then, the monarch (currently Queen Elizabeth II) travels from Buckingham Palace to Westminster by horse-drawn carriage, and members of the armed services stand along the route of that processional. Shortly thereafter, the members of the House of Commons are invited into the House of Lords. The Queen addresses both houses, the members of which are expected to remain silent throughout, neither applauding nor jeering.

Oh, and before all that happens, the Queen takes herself a hostage — some collateral in case Parliament doesn’t let her leave.

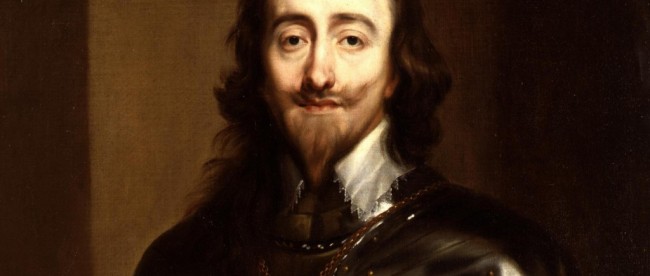

That precaution seems unnecessary today, as the Queen and Parliament get along nicely (and when the two disagree, it doesn’t get that bad). But not all British monarchs had a such peaceful relationships with their legislative bodies. Specifically, there was King Charles I, who ascended to the throne in 1625. Charles’ time as king was marred by on-going arguments with Parliament over the bounds of his power, and ultimately, Parliament won — Charles I’s reign ended in early 1649 when the executioner’s blade removed his head from the rest of him. The acrimony between Charles I and Parliament — and the end result — is something that the current Queen is reminded of every year during the State Open; her robing room has a copy of Charles I’s death warrant prominently displayed, as a warning for what happens when a monarch visits a hostile Parliament without a proper insurance policy.

So to ensure the monarch’s safety whenever he or she visits Parliament, there’s a hostage situation built into the traditions of the day. Specifically, before the Queen leaves Buckingham Palace for Westminster, three members of Parliament come to the Palace — the Treasurer, Comptroller, and a government whip titled the Vice-Chamberlain of the Household — to bring honorary white staves to Her Majesty. And typically, the Treasurer and Comptroller are free to go. But, as Parliament’s official website notes, the Vice-Chamberlain remains behind, his or her fate tied to that of the Queen’s.

Yes, this is all for tradition’s sake nowadays, but as Wikipedia notes, while “the Vice-Chamberlain’s imprisonment is now purely ceremonial [. . .] he does remain under guard” until the Queen is safely returned. And so far, none of the Vice-Chamberlains are still under lock and key, and more importantly, none have met their demise during the State Opening.

Bonus Fact: Every year, the President of the United States addresses both houses of Congress in what is known as the “State of the Union” address. It’s customary for the Vice President and the members of the Cabinet to also attend, which means that collectively, every member in the presidential order of succession is invited and, therefore, may all be in the same place at the same time. From a national security perspective, that’s an awful idea, so one President-eligible cabinet member at random is selected to not attend. Instead, this person, dubbed the “designated survivor,” is given a security detail equal to that of the President and transported off to a secure, undisclosed location until the end of the event. (The “designated survivor” program is also used for similar events where many if not all of those in the order to succession are present.)

From the Archives: Wine and Cheese with the Queen: An uninvited guest in Buckingham Palace.

Take the Quiz: Identify the famous Charles.

Related: “Charles I: A Life of Religion, War and Treason.” 4.5 stars on 8 reviews.