The Race to Determine the Fastest Man Alive

The informal title of “World’s Fastest Man” is typically given to the person who wins the men’s 100-meter dash in the Olympics. In 2016, that went to Usain Bolt, who won gold not only in that event but also in the 200-meter dash (and the 4x100m relay). While Bolt is an exception: it’s actually pretty rare for someone to be the world’s best at both the 100m and 200m races. And in one case, those two winners both laid claim to the “World’s Fastest Man” title.

So, they raced.

The 1996 Olympic Games in held in Atlanta, Georgia. Canadian sprinter Donovan Bailey won gold in the 100m race, setting a world record of 9.84 seconds and establishing himself as the fastest man alive, given the criteria above. American runner Michael Johnson took gold in the 200m, setting a world record of his own, at 19.32 seconds. The story should have ended there, but television got in the way. NBC’s long-time Olympic host/commentator Bob Costas made a seemingly innocuous observation on-air, noting that Johnson’s time, divided by two (that is, pro-rated to 100 meters), came out to 9.66 seconds — 0.18 seconds better than Bailey’s. If Johnson can run faster for a longer distance, shouldn’t he be the World’s Fastest Man?

The short answer is no, he shouldn’t. The top prorated 200-meter time is almost always faster than the 100-meter time because for the second hundred meters, the racers aren’t starting from a stop — there’s no need to accelerate and you don’t have to double the tiny but significant reaction time from when the starting sound plays. A faster 200m has long been the norm. As Wikipedia notes, “each 200 metre gold medalist from 1968, when fully electronic timing was introduced, to 1996 had a ‘faster” average speed at the Olympics, save one, yet there had been no controversy over the title of ‘world’s fastest man’ previously, until Bob Costas’ remarks during the 1996 Olympics.” That’s even true when the same runner wins both races. Take the 2016 Games, for example — Bolt’s gold-medal winning 100-meter race took him 9.81 seconds, but his gold-medal winning 200-meter race took him only 19.32 seconds, or 9.66 seconds per 100 meters.

And yet, the controversy simmered — and then boiled over. Costas and other NBC commentators kept making the point. The American sports press didn’t let the made-up controversy go, with Sports Illustrated writing about the disputed made-up-anyway title. Race organizers, looking to capitalize on the attention this North American feud had stirred, began pitching the runners on a showdown.

Ultimately, that’s exactly what they agreed to. After months of boxing-like promotions, on June 1, 1997, the two runners met in Toronto for a unique 150-meter race, splitting the difference between their two favored formats. Bailey and Johnson, alone, would take to the track, starting on a curve and ending on a straight-away. Each racer earned $500,000 simply for showing up; the winner was to take an addition $1 million home. Johnson even offered to put the $500k appearance fees in the pot, making it a $2 million winner-take-all, but Bailey declined, saying “Why would I do it? This is my job, remember?”

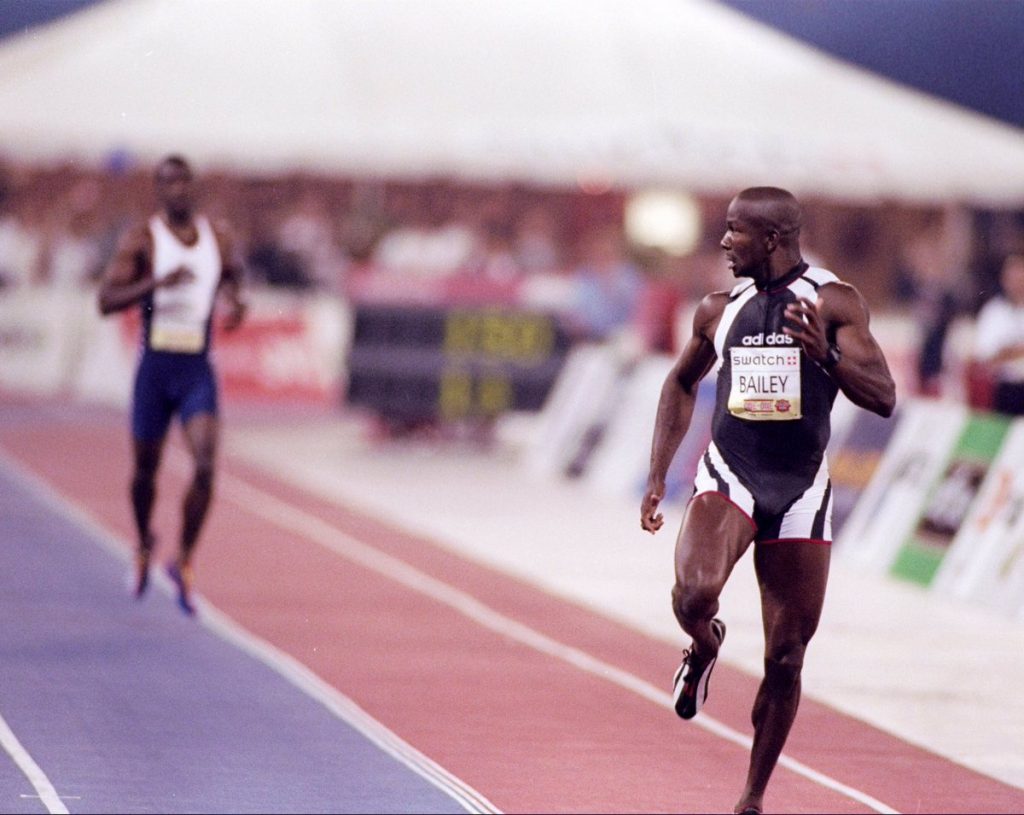

And Johnson is lucky that he did. You can watch a video of the race here and you’ll see, it wasn’t much of a contest. Bailey overtook Johnson out of the turn into the straightaway, giving the Canadian a lead for the part which should have been Bailey’s strength. But it didn’t matter. With about forty meters to go, Johnson pulled up, came to a stop, and fell to one knee, and Bailey glanced back (as seen above), winning easily. Right after the race, in the heat of the moment, Bailey reacted angrily, telling a CBC reporter that Johnson “didn’t pull up at all — he’s just a chicken. He’s afraid to lose. I think what he should do, we should run this race over again, so I can kick his ass one more time.”

They never did. Track’s sanctioning body, the IAAF, disapproved of the race beforehand; they were downright scornful of it after, calling it circus-like, and refused to authorize a rematch. But even if they had, Johnson was legitimately injured; he had pulled a quad muscle and ended up missing the U.S. Outdoor Track and Field Championships later that year. He also declined to defend his 200 meters title in the 1997 World Championships (although he did successfully defend in 400 meters title). Bailey competed in the 100 meters at Worlds but finished in second. As such, there hasn’t been a similar 150-meter race since.

Bonus fact: Usain Bolt’s running stride isn’t as smooth as you’d expect. In fact, it’s not smooth at all. His right leg is a half-inch shorter than his left; as a result, per the New York Times, “his right leg appears to strike the track with about 13 percent more peak force than his left leg. And with each stride, his left leg remains on the ground about 14 percent longer than his right leg. ” But does that slow him down, or help make him as fast as he is? As of 2017, researchers at Southern Methodist University who were studying Bolt’s gait were undecided, having come up with explanations in both directions.

From the Archives: A Nugget of Speed: Usain Bolt’s secret weapon?