The Writing Was on the Wall

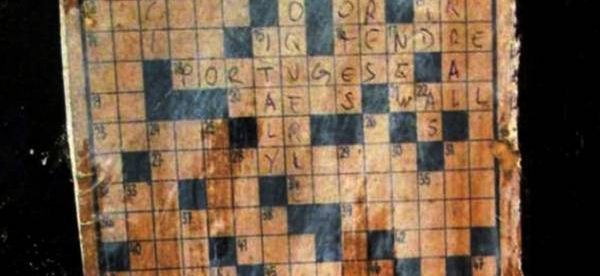

Crossword puzzles are, at least in theory, pretty simple. There’s a grid with some blank spaces in which you can write words, one letter per space. Of course, there’s usually a wrinkle – the words you write should match the clues provided. But the crossword pictured above? It’s a little different.

It’s incomplete – lots of empty squares. And it looks old and faded, right? You’d think that, by the time the puzzle began to yellow like that, it would have been solved. And in the summer of 2016, it finally was – kind of – courtesy of a 91-year-old German woman named Hannelore K. whose surname has gone unreported due to the country’s privacy laws.

Why keep her identity a secret? Because by “solving” this problem, our unnamed hero was – accidentally! – committing a crime.

At the time, the crossword pictured above hung on the wall at the Neues Museum in Nuremberg, Germany. Our nonagenarian of the moment was at the museum as part of a field trip of sorts; a group of senior citizens traveled together to take in some culture. Per the BBC, “Gerlinde Knopp, who was leading the excursion, said the museum was also full of interactive art, making it easy to lose sight of what one could and could not do there.” And a sign next to the crossword — in English — shared the work’s title: “Insert words.” Taking “insert words” as an instruction, she dutifully went to work — she took out a ballpoint pen and began to write some words into the blanks provided.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t one of the museum’s interactive pieces. It was a work by an artist named Arthur Köpcke, a German artist who died in 1977. The piece was appraised — before the accidental vandalism — at a value of about $90,000. And Hannelore K. had just written all over it. Oops.

The museum filed a police report in the matter, but don’t worry, they didn’t send any 91-year-olds to prison. Eva Kraus, the museum’s director, told the Telegraph that “we do realize that the old lady didn’t mean any harm; nevertheless, as a state museum couldn’t avoid making a criminal complaint. Also for insurance reasons we had to report the incident to the police.” And even better, the harm done to the canvas was minimal — restoration only cost a few hundred Euro, a cost the museum was able to shoulder.

But the matter didn’t end there. Because the museum was forced to report the “crime,” the police felt compelled to investigate further. So Hannelore K.’s lawyer fought fire with fire. The argument? Per ArsTechnica, “[her lawyer] says that far from harming the work in question, his client has increased its value by bringing the relatively-unknown Köpcke to the attention of a wider public.” And because her additions added value to Köpcke’s original piece, the attorney further argued that Ms. K. “now held the copyright of the combined artwork—and that, in theory, the private collector might sue the museum for destroying that new collaboration by restoring it to its original state.” Her accidental vandalism was, they argued, art itself.

The English-language press hasn’t followed up on the outcome of the matter, but it’s safe to say that the original work, once restored, was returned to the museum wall for the remainder of the exhibition (and that the accidental vandal was never jailed nor compensated for her “creation”). One thing is certain, regardless: the sign next to Köpcke’s work no longer reads “insert words.” Reported the Telegraph: “the museum said that in future it would alter the label for the work to make it clear visitors were not permitted to fill in the blanks.”

Bonus fact: The study of puzzles — academically speaking, that is — is called enigmatology. There’s only one person known to have a degree in it, a guy named Will Shortz. Indiana University has something called the Individualized Major Program, or IMP, in which undergrads can “forge [their] own educational path ” by designing a courseload and coursework which, upon completion, earns the student a bachelors in their chosen field. Shortz, an IMP student, graduated with the world’s only enigmatology degree in 1974. But before you write his self-made degree off as a joke, check out Shortz’s bio — he’s put it to good use. Not only the editor of the New York Times crossword (since 1993), but he also serves a similar role with NPR and has written or contributed to more than 100 puzzle books.

From the Archives: Cross Words: The crossword puzzle which (accidentally?) predicted D-Day.