Untying the Not

In Judeo-Christian religions, the Ten Commandments are generally regarded to be of elevated importance (or, at least, are better known than many of the other rules). For Jews, Protestants, and Catholics, the ten rules are generally the same, but there are some slight differences mostly when it comes to enumeration. For example — and you can see a breakdown of the commandments here — in both Judaism and Protestantism, the seventh commandment is “thou shalt not commit adultery,” but that’s the sixth commandment in Catholicism. So if you pick up a Bible and see that the numbering isn’t what you’re familiar with (if you’re familiar with the numbering in the first place), that’s why. But in general, the words are going to be roughly the same thing.

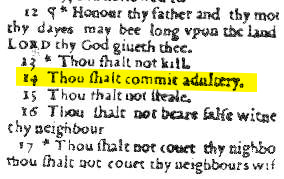

Except for this one bible printed in 1631. That one got the sixth/seventh commandment, well, wrong. Check out the picture below.

See the word “not” on the highlighted line? No? That’s because — oops! — it’s not there. The commandment reads: “Thou shalt commit adultery.” And again, that’s a commandment, not a mere suggestion.

Now, typographical errors happen, as those of us who write (and read) hastily-edited email newsletters can attest. And they’re typically not a big deal, as readers are intelligent enough to realize the error and infer the intended word or phrase. Most likely, that was the outcome in England in the 1630s as well — it’s not like this errant passage led to a surge in married men sleeping with women other than their wives. But bibles with mistakes like this in pre-Enlightment England can create atypical results, apparently. First, rumor spread that the omission was intentional, but in jest. Then, the bible was colloquially referred to as the “Wicked Bible” or “Sinners’ Bible” and was denounced by both King Charles I and the reigning Archbishop in the area at the time, as the Guardian noted:

King Charles I, apprised of the error by the Bishop of London, summoned the frightened and mortified printers to the Star Chamber, revoked their licence, and fined them £300 – some £35,000 [$50,000 or so] in today’s money. The Archbishop of Canterbury was scandalised and, in those Puritan times, unwilling or unable to conceive of the mistake as a hoax. He blamed the whole sad affair on shoddy standards in the industry: “I knew the tyme when great care was had about printing, the Bibles especially, good compositors and the best correctors were gotten being grave and learned men, the paper and the letter rare, and faire every way of the beste, but now the paper is nought, the composers boyes, and the correctors unlearned.”

(Apparently, to the Archbishop, it was worse to have unqualified bible makers than jokester ones.)

About 1,000 of the bibles were printed and they were ordered to be destroyed — burned — and those that had already been distributed were recalled as best as possible given the restraints of the era and, for that matter, the error. There are now only about a dozen of the books known to be in existence. The forced scarcity created by the recall and destruction of the bibles made the Wicked Bible into a collectors item — on which, if you happen to have one laying around somewhere — is worth in the realm of $100,000.

Bonus Fact: King Charles I was the only English monarch to be tried for treason and executed. He was beheaded on January 30, 1649. His last request? A second shirt. Wikipedia explains that the second shirt was because the forecast was for a cold day, and Charles requested the additional layer “to prevent the cold weather causing any noticeable shivers that the crowd could have mistaken for fear.”

From the Archives: The Oldest Emoticon: It may be a typo. Or it may be awesome.

Related: “Just My Typo: From ‘Sinning with the Choir’ to ‘the Untied States’” by Drummond Moir. 4 stars on 39 reviews.