When Candy Land was the Game of Life

If you’ve ever played a board game, chances are, you’ve played Candy Land. Good for ages three and up, it’s the gateway to the board gaming world for almost everyone, selling north of a million copies a year. It’s a super-simple game with virtually no nuance; Candy Land requires no reading skills, almost no counting skills, and has no strategy whatsoever. In fact, the outcome is predetermined; the pre-shuffled deck of cards one draws from dictates the outcome entirely. (As a parent of formerly-young children, this had the added advantage of ensuring that the child in question would be certain to win the game, and quickly, but that is another story.)

As a result, once children are old enough for virtually any other activity, Candy Land becomes very boring. There’s little reason to play it unless you are very little or very, very bored.

Like a kid in a polio ward.

Until Jonas Salk developed a polio vaccine in 1955, the disease ravaged communities in the U.S. and around the world. In 1952 alone, as previously noted in these pages, “roughly 58,000 new cases of polio were reported across the United States. Over 3,000 of those people died and another 20,000 — mostly children — were left with some degree of paralysis.” Many hospitals set up polio wards to help those afflicted, and in many of those wards, children were instructed to stay in bed (or in iron lungs, as seen here) for most of the day. Boredom was not just a way of life, but also seen as a key element to their survival and long-term health.

In 1948, a teacher named Eleanor Abbott was one of the many who fell ill with polio. While recuperating at a hospital in San Diego, California, Abbott decided to engage with the children in the ward. Per the National Toy Hall of Fame, Abbott “sought to invent pastimes for children who were recuperating,” developing all sorts of games and activities for them during their hour or two of free time.

One of those games was nothing more than a winding path sketched out on butcher paper, which is to say the precursor to Candy Land. The children seemed to enjoy this game — in the very least, it was a nice reprieve from hours of doing nothing. As the Atlantic put it, “in theme and execution, the game functions as a mobility fantasy. It simulates a leisurely stroll instead of the studied rigor of therapeutic exercise. And unlike the challenges of physical therapy, movement in Candy Land is so effortless, it’s literally all one can do.” And the game proved popular in Abbott’s ward. Friends encouraged her to shop the design to game manufacturers, and Milton Bradley ended up purchasing the rights.

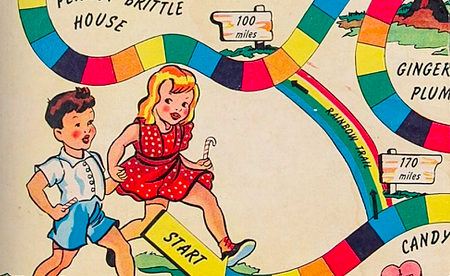

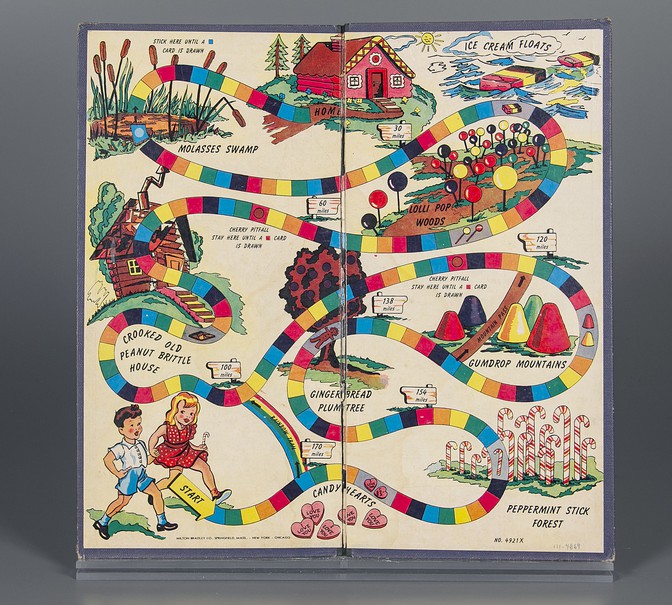

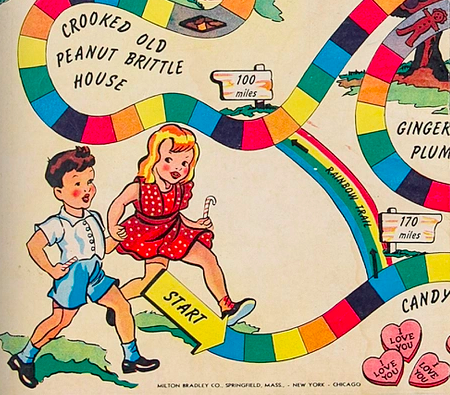

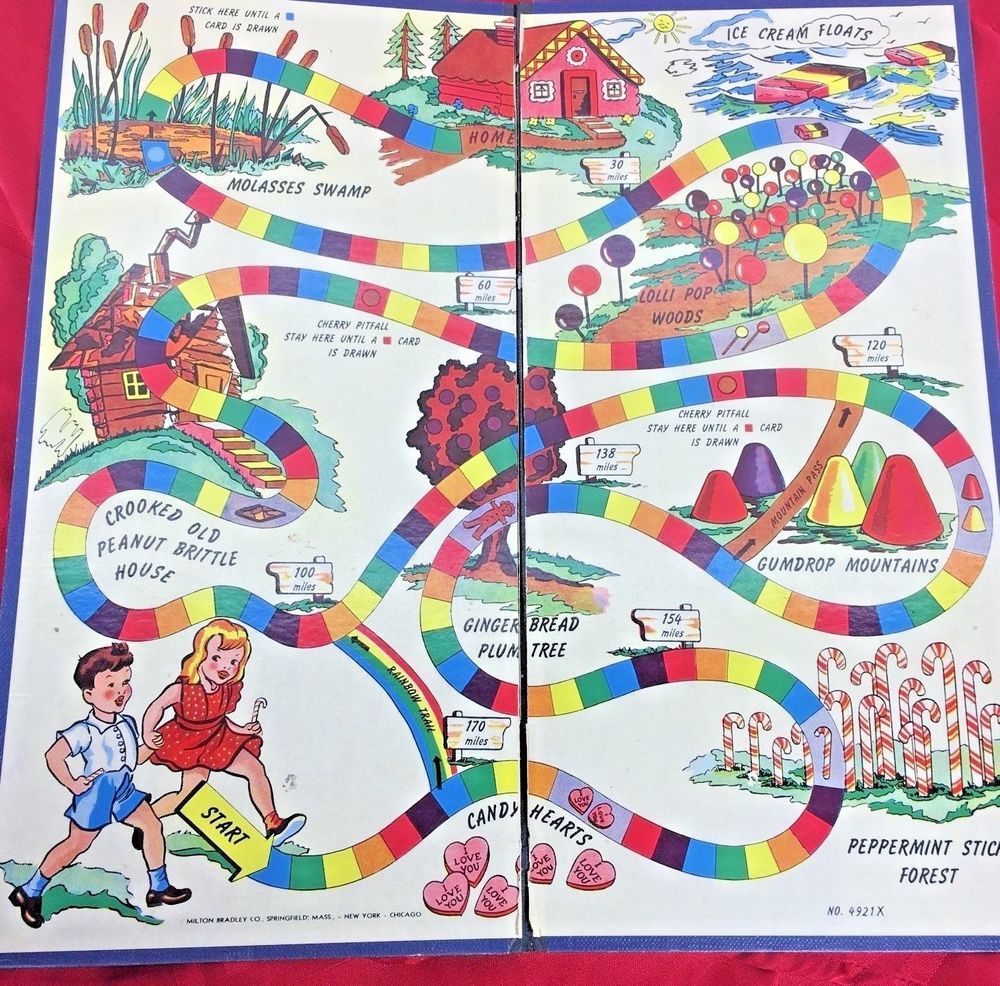

The first commercial version of the game came out the next year; you can see the game board above (via the National Toy Hall of Fame). And if you look closely at the boy pictured, there’s a line running down the outside of his right leg. A closer look is below.

That line? Most likely, it’s intended to depict a brace used by those kids by polio.

And while most children — and therefore, most customers — weren’t in polio wards, the fear of the disease was still probably responsible for Candy Land’s initial success. In an article in the Journal of Play (pdf here), candy historian Samira Kawash argued that parents didn’t want their kids playing outdoors or interacting with too many other kids. As a result, Kawash outlines, Candy Land became a good way to pass the time:

But among all the possible reasons parents purchased Candy Land, one particular appeal was directly related to the historical context of anxieties and fears surrounding polio: Candy Land offered parents a reassuring alternative to the dangers lurking outside the house. As historians have observed, the fear of polio in the late 1940s and early 1950s curtailed children’s free play. A combination of popular superstitions and a lack of medical knowledge about the means of transmission led to the suspicion that polio might lurk anywhere, from the water in public swimming pools to the sweet creaminess of ice cream cones bought at the corner shop. The fear, however unfounded, was that polio germs contaminated the traditional outdoor and public play spaces of childhood. But there was a safe alternative. Children could stay home and play inside. Candy Land was, in this context, something to do in the house. Advertisements for the game like one published by Rogers Toy Store in Washington, D.C., promised parents that “this indoor game . . . will keep your youngsters happy for hours.”

As the 1950s came to a close, the polio vaccine came into use and the epidemic faded, but Candy Land maintained its popularity. Milton Bradley (and now, Hasbro) has updated the game many times since. And one of the first changes? As seen below, they removed the boy’s leg brace.

Bonus fact: Candy Land has a small part in polio’s history and also a small part in the history of the internet. In 1996, when the consumer web was still in its nascent stages, the laws of the information superhighway were unclear at best. In all the chaos, and adult website (yes, that kind of “adult”) registered the Candyland.com domain name. If you had clicked that link, you would not have been sent to anything even remotely kid-appropriate, and that was a problem for the game’s owner, Hasbro. So they ran to court. In one of the first-ever court cases over trademarks and domain names, Hasbro successfully prevented the website from operating at that address.

From the Archives: Before Salk: The story of the polio vaccine pre-Salk’s.