When the U.S. Air Force Bombed Montana

If you were serving in the U.S. Armed Forces in the early part of 1944, there’s a pretty good chance you were doing so abroad. World War II was in full swing, and America was fighting in both the Pacific and in Europe. But on March 21st of that year, the military had another target: America itself.

Specifically, it bombed the town of Miles City, Montana.

Miles City is located in the southeastern part of the state and, based on the 1940 and 1950 census, had between 7,500 and 9,000 over the course of that decade. It’s located just a few miles north of the Yellowstone River, a major waterway in the area. The proximity to the river made it a good location for a military base on the American frontier in the late 1800s. Over time, the need for a fort waned, but the people remained. Miles City later became a hub for ranchers in the area — it had a lot of open land nearby and the river provided a source of water for the herds.

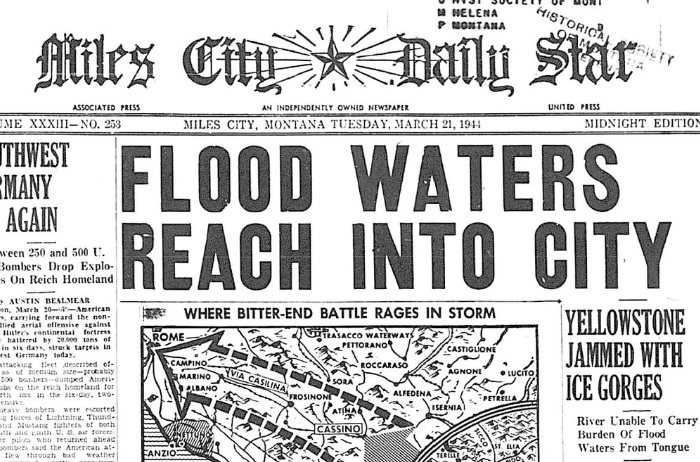

But the proximity to the Yellowstone River came with a complication. During particularly cold winters, parts of the river would freeze over. Big chunks of floating ice, collectively called ice jams, formed on the river’s surface, effectively clogging it up. In March of 1944, the front page of the local paper, as seen below, rang out a warning: the ice, acting as a dam, was making the river flood, and Miles City was getting the brunt of it. It was a disaster.

The problem would be solved once the ice jams cleared, but the people of Miles City couldn’t wait for the spring thaw. Approximately 300 families were rendered homeless within hours of the freeze and more were likely to suffer the same fate. So town officials did the only thing they could think of: they asked the military for help.

Specifically, they wanted the Air Force to bomb the river.

As the Associated Press reported, the Air Force (then part of the Army) sent in a bomber — a B-17 Flying Fortress — to assist the people of Miles City. The bomber had a payload of sixteen 250-pound bombs (which are, relatively speaking, small bombs, but they’re bombs nonetheless) and had the go-ahead to use them. After a couple of test flights, the flight crew dropped all sixteen, targeting the masses of ice in the river. What the resulting explosion looked like is unclear, but it may have been grand. For example, one source of questionable authority noted that “seconds later a huge plume of ice, mud and water exploded skyward from the frozen Yellowstone River.”

Regardless, one thing is for sure: the plan worked. Per the AP, “water and bomb-shattered chunks of ice surged down the Yellowstone River [. . .] just a few moments [after the bombing run}.” The ice jam cleared, the river receded, and Miles City was safe again.

Bonus fact: Ice jams aren’t made of icebergs — the ice jam ice is too small — but the basic idea is the same. But what happens when the air-exposed part of an iceberg melts and the part underwater doesn’t? The iceberg flips over. And as a result, it may turn blue, as seen here. (Those little black dots are penguins.) As Planet SEED explains, “the ice in glaciers has been under enormous pressure for eons. The compression eliminates air and reflective surfaces within the ice.” As a result, “when light hits the iceberg, it no longer bounces off. Instead, the light is absorbed. As in water, the longer (red or green) visible wavelengths of light are absorbed, so the light leaving the ice will be blue or blue-green.”

From the Archives: How to Land a Plane By Leaving It: Another story of airplanes, Montana, and how they shouldn’t have come together (but did).