When You’re Glad The Bank Isn’t Trustworthy

In the fall of 2010, Markus Persson, creator of the hit video game Minecraft found himself in a bit of a financial mess. At the time, fans of the fledgling-but-popular game purchased it through PayPal — and PayPal wasn’t used to seeing huge sums of money flow through its platform. When Persson went to withdraw the $750,000 he had amassed in his account, PayPal said no — they needed to verify that he wasn’t up to something illegal. But there are plenty of situations where funds are held indefinitely. Banks, in general, keep an eye out for criminals who are using the institution as a way to get ill-gotten gains into the normal, above-board economy. In those cases, law enforcement is contacted instead.

And then there was RHS Trust, which did the exact opposite.

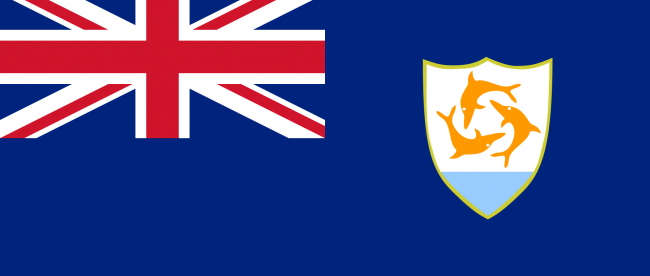

RHS Trust was a bank on the small Caribbean island of Anguilla. A British overseas territory, Anguilla is home to roughly 15,000 people but still has a robust banking system; due to its very favorable tax laws, it is a great place for the very rich out there to park cash. And similarly, the government there asks few questions about where the money comes from, which is in part why RHS Trust decided to start its operations there back in 1992. Colombian drug lords were awash in cash but needed a way to launder the money — it’s hard to clean millions of dollars each week — and the people behind RHS Trust saw an opportunity. By starting a bank in Anguilla, they believed they could be the beneficiaries of these drug cartel’s laundering woes.

By 1994, the RHS Trust was up and running, taking deposits from these illicit clients. It was, as NPR reported, an intricate process: “the big Colombian cartels would send a fax saying they had cash in New York City or wherever. Someone would arrange a pickup, and the cash would be deposited in an account. [ . . . ] The money laundering world was surprisingly vast and sophisticated, with money hidden in the normal flow of international trade, in payments for things like tractor parts.” In total, the bank took in cash deposits of more than $40 million (worth about $68.5 million in today’s dollars) as well three high-end paintings (including a Picasso). If RHS Trust had shareholders, they would have considered the unscrupulous bank a financial success.

But the bank wasn’t backed by investors. In fact, it wasn’t really a bank. It was a Drug Enforcement Agency sting operation.

The ruse, called Operation Dinero, exposed previously unknown details about the underworld of the international drug trade. And it was extensive — and successful. Reported the New York Times, “undercover drug agents began promoting [the fake bank’s] services to criminal contacts in Colombia and elsewhere. Then through transactions involving loans, cashiers’ checks, wire transfers and currency exchange, officials said they were able to trace the money from Colombia and then to sources the brokers were using around in the United States, Europe and South America.”

In total, per the DEA, Operation Dinero “resulted in 88 arrests, the seizure of approximately 9 tons of cocaine, and the confiscation of well over $50 million in cash and other property.” And perhaps more importantly, as NPR further noted, it made it more difficult for the drug trade to operate in the future — it “made drug dealers wary of using banks to launder their money,” leaving cartels with fewer options to do so.

Bonus fact: Perhaps, instead of setting up a fake bank, the government should have just sent a subpoena to a real one? In 2012, according to Rolling Stone, international banking giant HSBC “admitted to laundering billions of dollars for Colombian and Mexican drug cartels.” The methods, per the magazine, were “brazen” — citing a government official, “drug dealers would sometimes come to HSBC’s Mexican branches and ‘deposit hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash, in a single day, into a single account, using boxes designed to fit the precise dimensions of the teller windows.'” HSBC was fined just under $2 billion for the crime, which sounds like a lot, but the bank could afford it: in 2012, HSBC had a net annual income of more than $13.4 billion.

From the Archives: Why the U.S. Government Really Wants Some People To Take Vacations: Vacations — they’re not just fun. They’re a fraud-detection technique.