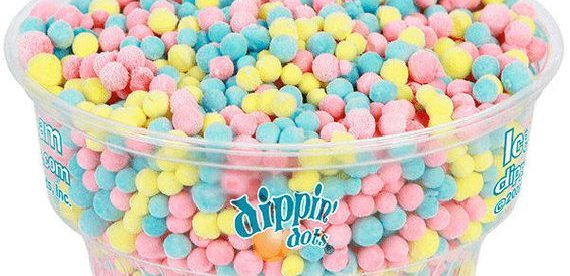

Why Dippin’ Dots Never Became the Ice Cream of the Future

Dippin’ Dots, pictured above, are a form ice cream which was invented in 1988 by an Illinois guy named Curt Jones. Jones, a microbiologist by training, was working in cryogenics — that is, the physics of freezing stuff at super-low temperatures. For the most part, cryogenics was (and is) used in industrial settings, and Jones was working on such an application; per Mental Floss, he was trying to freeze yogurt for use in animal feed. He realized he could apply the same technology to a combination of milk, cream, sugar, and flavorings and make something for us humans, too. The end result: pellets of flash-frozen ice cream which, when mixed, formed flavors like chocolate chip cookie dough, banana split, and cotton candy.

And it proved popular. One could find Dippin’ Dots at mall kiosks, amusement parks, and the like, delighting children and adults alike. The brand adopted the moniker “The Ice Cream of the Future,” promising to become a staple of dessert courses near and far. It made sense, right? Who doesn’t like futuristic ice cream? All Dippin’ Dots needed to do to fulfill on its promise was to find its way into your grocery’s freezer, allowing anyone to bring it home with them.

And yet, here we are, thirty years later. And not only isn’t there any Dippin’ Dots in our freezers, there often isn’t any in our malls either. If anything, Dippin’ Dots are even harder to find. What happened?

Blame your freezer. And the freezers at your local grocery store, too.

Your freezer — and the one at the supermarket, for that matter — probably doesn’t get any colder than 0°F (about -17.77°C). That’s by design. By and large, the food safety benefits of going below 0°F are minimal — you’ll be able to store food items at that temperature for months, and going a little bit colder isn’t going to gain you much extra time. On the other hand, the energy needs to maintain lower temperatures are significant. And really extreme temperatures — say, -40°F (-40°C) are simply out of reach given the cooling systems of most modern freezers.

But Dippin’ Dots? They need to be stored at -40°F.

In small amounts with specialty equipment, that’s easily doable — the ice cream pellets are kept frozen at temperatures of -320°F (-195.5ºC) using liquid nitrogen, and then stored in a similar fashion in that little stand at the zoo near the penguin exhibit or stroller rentals. But that hasn’t stopped the company from trying to bring Dippin’ Dots into your home. You can order big bags of 30 servings off the Dippin’ Dots website. It arrives packed in dry ice — that is, solid carbon dioxide — but Dippin’ Dots warns that you better eat the ice cream quickly because it “cannot be stored in a home freezer.” And in 2016, the company began rolling out specialized freezers for retail locations like grocery stores, but that’s generally proved unpopular. Consumers would have to pay a premium price due to the storage costs, and they’d have to eat the product right away — there aren’t many of us who have these special low-temp freezers at home. And what kind of future does a product like that have? Not much of one.

The company declared bankruptcy in 2012 due to low cash flow and while they came back under new ownership, they’re still trying to figure out how to grow. (One avenue they’re looking at? Selling cryogenic equipment to other industries.) Unless the world gets colder, Dippin’ Dots’ self-claimed desire to become the ice cream of the future will remain unfulfilled.

Bonus fact: Dippin’ Dots obtained a patent on their ice cream making process in 1992 but it isn’t worth that much. In 1996, they sued a competitor called Mini Melts, claiming that Mini Melts’ product and process were virtually identical to Dippin’ Dots. The Melts won despite the fact that their product, seen here, is very similar to the Dots (although less dot-shaped). Why? Because while we may think of Dippin’ Dots as special, the court didn’t agree. Rather, it ruled that the process of making Dippin’ Dots was “obvious” and not something that can be protected by a patent.

From the Archives: Ice Cream, You Scream: When Glasgow went to war via ice cream trucks.