Why The $1 Bill Doesn’t Change

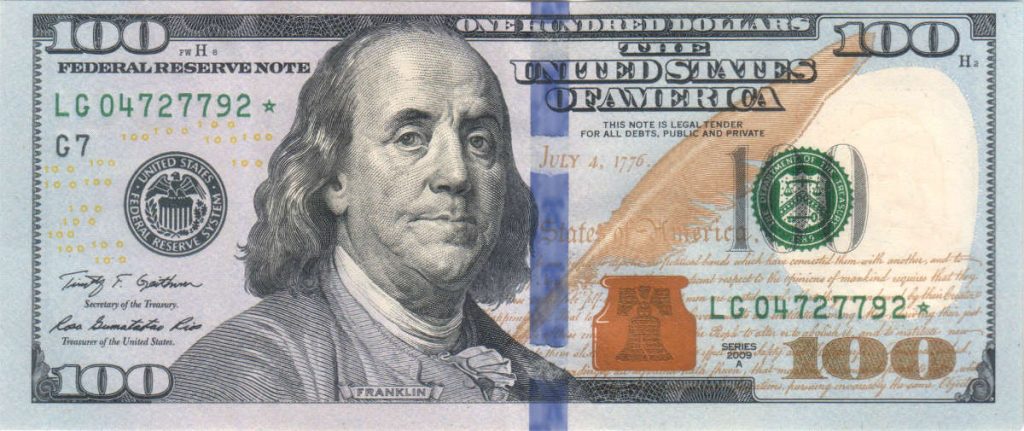

If you look in your wallet right now, hopefully, you’ll see some money in there. If you’re an American, you may see some mix of $1, $5, $10, $20, $50, and $100 bills. (There may also be a rogue $2 bill in there, but let’s not worry about that.) Most of those denominations have huge portraits of past American leaders on them — take note of the size of Ben Franklin’s head on the image above — but there’s one exception. The one-dollar bill, pictured below, has a relatively smaller picture of George Washington adorning its center.

And that’s hardly the only difference, either. The $100 bill is more colorful, has a watermark, and all sorts of design doodads throughout. It’s not alone among bills that way, either. The $20 bill, as of 2003, “features subtle background colors of green and peach,” “an embedded security thread that glows green when illuminated by UV light,” a watermark, and “a color-shifting numeral 20 in the lower right corner of the note,” according to USCurrency.gov. The $5, $10, and $50 all now have similar features. Over the past decade or two, each has gone under a significant redesign.

But the $1 bill has gone mostly unchanged since 1929. Why hasn’t George gotten an upgrade?

The decision to redesign paper currency stems not from the dreams of an idle artist but, primarily, from the security needs of a nation. Specifically, the issue here is counterfeiting: it’s bad for everyone (except the counterfeiter) if fake money is circulating, so the government takes steps to make that difficult. Older bills lack the security features of their newer counterparts and are therefore easier to fake. For larger-denomination bills, that’s a big problem, but it’s questionable if that problem spreads to smaller denominations like the $1. Making fakes takes money and comes with considerable risk — and besides, think about how awkward it would be to buy a big-ticket item (like, say, a new television) in cash using a huge wad of singles. (A stack of one hundred $1 bills is nearly a half-inch thick; $500 in singles would be a stack more than 2” tall.)

As counterfeiting of $1 bills isn’t a huge problem, the government hasn’t made updating the currency a priority. But, every few years, the issue comes up again, perhaps just for consistency’s sake. And just as suddenly, it goes away — once Big Snack enters the picture.

Okay, there’s no such thing as “Big Snack.” But there are a lot of vending machines in the United States, and those vending machines take $1 bills. And the $1 bill readers on those machines are built for the currency pictured above. And the owners of those machines formed an industry group called the National Automatic Merchandising Association, a trade organization and lobbying arm. Whenever the Treasury floats some ideas for a new George, the vending lobby fights back — successfully, to date.

For example, rumors of a new $1 bill swirled in late 2015 — but went nowhere. That’s because Congress acted. That December, Congress passed an omnibus spending bill, funding the government for much of the upcoming year. Buried in the 2,200+ page document was a rule explicitly preventing the Treasury Department from redesigning the $1 bill. The reason? As Politico explains, it was “the vending lobby.” This group of businesses “doesn’t want to spend money having to update its machines to recognize a redesigned $1 bill. Since few people try to counterfeit the $1 bill—the reason that Treasury normally redesigns currency—the lobby argues there’s no good reason for a redesign.”

That’s nothing new for the vending lobby, either; NAMA has strived to block such redesigns over and over again. According to the Atlantic, in 2006, a vice president of NAMA stated, quite transparently, that “as long as the $1 bill is around, NAMA will work to preserve the current design of the bill, the same design we’ve had since 1929. Redesign would be very costly to our operator members.”

So as long as people like potato chips, sodas, and candy bars, expect the bills to remain as-is — unless someone figures out a profitable way to counterfeit George Washingtons.

Bonus fact: NAMA also lobbies the government to replace old bills regularly — a well-worn dollar bill can’t be used in a vending machine, after all. The government generally agrees, recalling, shredding, and replacing these bills often. But what do they do with the old, shredded bills? According to the History Channel, you may be living in them: “in some cases, the federal government has sold the shredded currency to companies that can recycle it and use it for the production of building materials such as roofing shingles or insulation.”

From the Archives: The Moneymaker: Okay, so someone did, in fact, try to make a living out of fake $1 bills after all.