Why You Can’t Steal First Base

Baseball is a simple game — well, simple enough. As a batter, you need to get on base, which isn’t all that easy, but thankfully something we don’t have to address right here. As a runner, though, it’s pretty straightforward. You go from first base to second, then to third, and then home. If you do that, your team scores a run, and the team with the most runs wins the game. So, typically, baserunners run the bases in that order.

There are some occasions in which a runner may need to run the bases in reverse order — but if you do so, you really do need to have a good reason. If you’re just trying to sow chaos, you’re going to run afoul of the rules of the game, specifically Rule 5.09(b)(10). It reads:

After he has acquired legal possession of a base, he runs the bases in reverse order for the purpose of confusing the defense or making a travesty of the game. The umpire shall immediately call “Time” and declare the runner out.

Or in other words: Once you hit second base, you can’t run back to first just for fun.

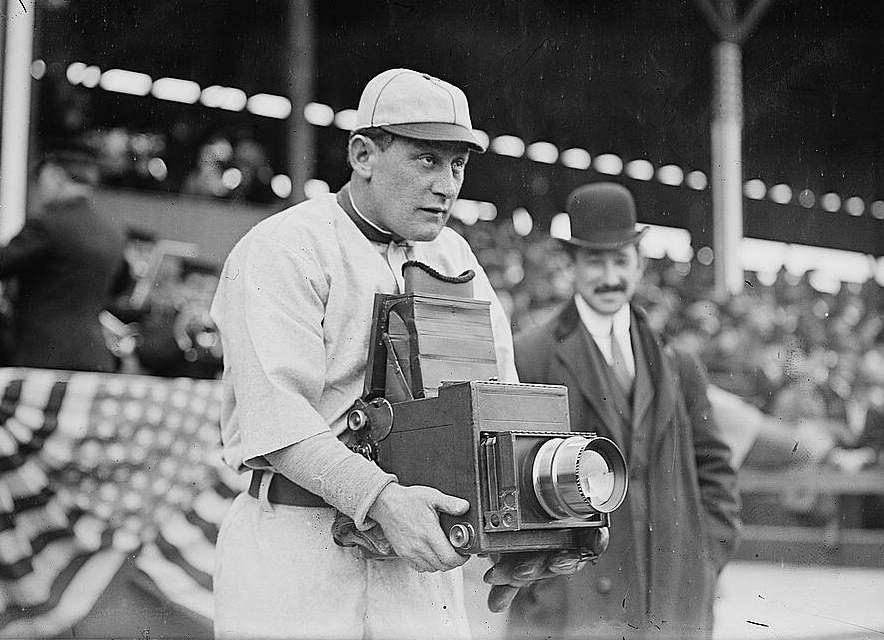

But — why would anyone do that anyway? The point is to go forward, not backward. Well, like most other weird rules, there’s some history behind this one. Credit this one to Germany Schaefer, who in 1911, was the first baseman for the Washington Senators, the predecessor of today’s Minnesota Twins. (He’s the guy pictured above, holding a camera for some reason.)

At the time, having runners on first and third and fewer than two outs was an invitation for the men on the basepaths to try some subterfuge. The runner on first would try and steal second, hoping to draw a throw. The runner on third would then seize that opportunity to steal home. (Yes, that happens every once in awhile in the modern game, too.) A century ago, when athletes didn’t have as strong or accurate arms, the trick worked more often than you’d expect.

That’s what Schaefer was thinking on the afternoon of August 4, 1911, when his Senators were hosting the White Sox. The game was scoreless in the bottom of the ninth, with Schaefer on first and his teammate, Clyde Milan, on third. With two outs, the situation was perfect. Schaefer, a meaningless runner, broke for second, in hopes that the White Sox’s catcher would take the bait and try for the inning-ending out.

The gambit failed — the catcher simply held onto the ball.

But on the next pitch, Schaefer — now on second base — was off and running again. Not to third, which was occupied by Milan, but back to first. The idea, which per one questionable report was something he had tried earlier in the season, was to again try to elicit a throw from the catcher and, if not, steal second (again) on the pitch after.

The White Sox manager, Hugh Duffy, came out to argue whether this should be allowed, causing further chaos to ensue. Schaefer decided to take off for second base, again, while Duffy argued with the umpire, and this time, the catcher tried to throw him out. (Remember, it was 1911 — the rules were still pretty poorly defined.) Schaefer got caught in a run-down, Milan ran home, and the White Sox defense woke up in time to throw Milan out at home. Had Milan scored, the Senators would have won; instead, Schaefer’s chaos-inducing back-and-forth sprints had backfired.

But he wasn’t done. Schaefer tried to argue that the out at home shouldn’t have counted — the opposing manager was on the field, and therefore, he asserted, the play was dead. The umpires disagreed and let the whole ridiculous transaction stand, declaring the inning over. Ultimately, it didn’t matter, as the Senators won the game 1-0 in extra innings anyway.

Schaefer’s base-reversing gamble apparently wasn’t tried again for the rest of the decade (or if it was, it went unreported), but just to be sure, Major League Baseball added the “don’t run backward” rule quoted above in 1920.

Bonus fact: Let’s say there’s a soft line drive hit a few feet over the shortstop’s head. Thinking quickly, the shortstop throws either his cap or glove at the ball, knocking it down in an attempt to either catch it or, at least, keep the ball on the infield. The trick works, and the ball gently falls back to Earth where the shortstop makes the highlight-reel catch.

Is it an out? Nope. It’s going to turn the soft liner into a triple. According to the official Major League Baseball rulebook, if “a fielder deliberately touches a fair ball with his cap, mask or any part of his uniform detached from its proper place on his person” or “if a fielder deliberately throws his glove at and touches a fair ball,” the runner is awarded three bases.

From the Archives: One Spud, You’re Out: What if the catcher in the Schaefer story didn’t throw a ball, but instead threw something else?