Why You Should Whistle While You Work

For most of us, idly whistling while at work isn’t such a great idea. Not only does it potentially distract your co-workers, but it also may indicate to your boss that you’re tuned out and unfocused on the task at hand. But very few of us — none of us, really (well, maybe one of us) — is actor Bryan Cranston.

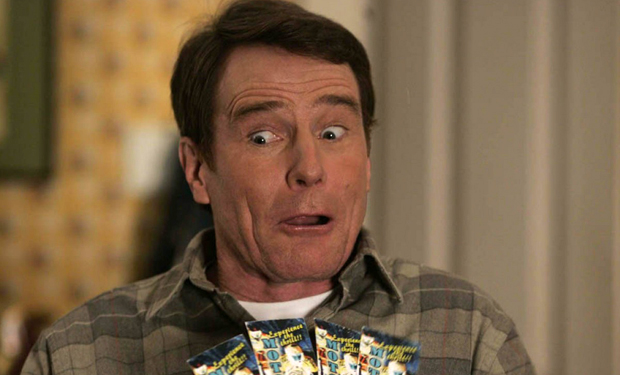

Cranston is probably best known for playing Walter White in “Breaking Bad,” and if White were to whistle aimlessly, that would have probably been out of character. But before Cranston played White, he was Hal Wilkerson, the dad in the sitcom “Malcolm in the Middle” (as above). As Hal, Cranston portrayed a dad of four boys who, himself, vacillated between being an adult and a really big kid. And as a respite from the stress of life with four often troublesome boys, Hal would, occasionally, take a mental vacation and whistle or hum an unfamiliar tune — the notes were whatever would come to mind

The whistles weren’t scripted, though. It was Cranston’s addition — the actor’s take on what his character would do. The writers, directors, and other members of the cast and crew didn’t think much of it, either; why would they? It was just an actor, acting, and doing so in a true-to-character way. Almost no one gave Cranston’s whistles a second thought.

But someone did. TV shows, movies, etc. often have songs or the like, and the performance, composition, lyrics, and other components of the music are typically under copyright. Someone working on the film has to “clear rights” to the music, which is to say that he or she has to figure out who owns the copyrights and then pay them for the use. To streamline this, assuming the musician is in the relevant guild, there are typically industry-standard fees associated with each use. (Especially for very small uses, it doesn’t make a lot of sense for either side to haggle over the price anyway.)

Cranston’s whistling caught the ear of the Malcolm in the Middle music rights clearance coordinator. Cranston was whistling a tune and someone, the coordinator noted, owned the rights to whatever he had whistled. The rights-clearance lead had to figure out what the song was, who owned what rights, and to cut a check — otherwise, the show producers would have to remove the whistle from the show. As this was a relatively small amount of money — perhaps a few hundred dollars tops — the preferred route would be to pay the music’s composer. But there was a problem: Cranston was improvising.

As Cranston told late night talk show host Seth Meyer (watch it here, including an impromptu whistling solo), the music rights management coordinator realized that Cranston was the copyright holder of the music he made up — and was, therefore, entitled to the royalty checks — if he joined the guild. So Cranston did just that, and, thereafter, received a small payment every three months.

His co-workers weren’t jealous, either — in fact, the opposite was true. As Esquire noted, he “used [the proceeds] to fund cast parties,” endearing himself to the crew. And the crew, unsurprisingly, encouraged him to whistle and hum on camera more often.

Bonus fact: Bryan Cranston isn’t the only thing Breaking Bad and Malcolm in the Middle share. If you paid attention to the minutia of each series, you may have noticed a few characters with cigarettes. (In Breaking Bad, which aired on cable TV station AMC, someone is smoking the cigarettes, but on the network TV show Malcolm in the Middle, they’re not.) And in both series, one of the brands of cigarettes on screen is called “Morley.” You can’t buy Morleys at the local gas station, though; it’s a made-up brand and they only exist as props — a very common prop. They look like Marlboros (see here) and were first used in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960s thriller Psycho. Since then, Morleys have made an appearance in nearly two dozen movies and more than 50 TV shows. There’s no rhyme nor reason why Hollywood adopted such a tradition.

From the Archives: Give a Little Whistle: Meet the people who communicate via a whistling-centric language.