The Radio Reporter Who Found a New Voice, Literally

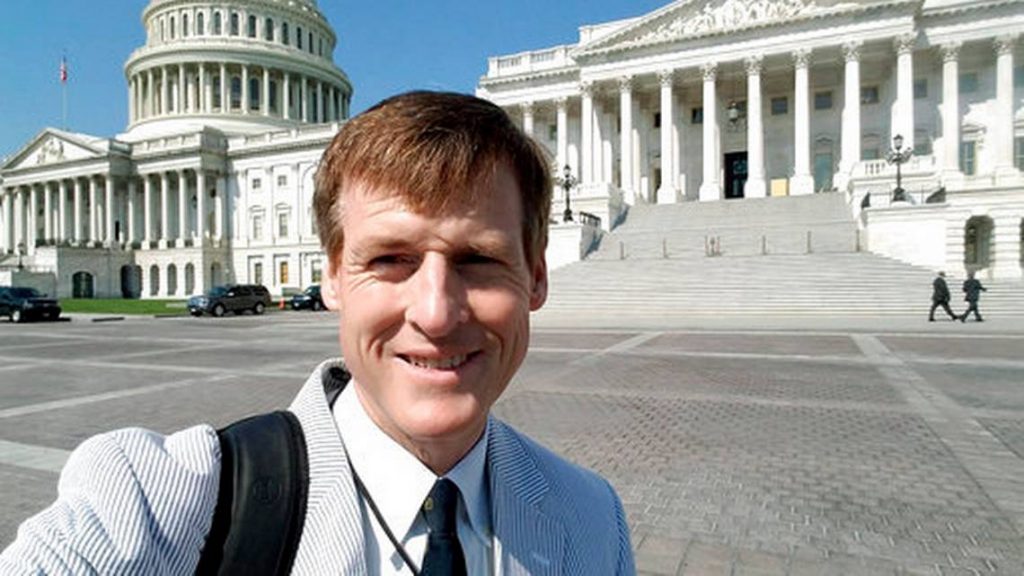

Jamie Dupree, pictured above is a political reporter. He got his start in the 1980s and by 1992 was covering presidential campaigns. For the most part, Dupree worked in radio — he worked for Atlanta-based Cox Media Group, which operates a few dozen stations across the country. That was true throughout most of the 2016 presidential campaign, but something changed. Dupree lost his voice.

It wasn’t laryngitis, though. And it wasn’t temporary.

In March of 2016, while the election was in full swing, Dupree and family went on vacation to London — think of it as a pre-convention reprieve — and he intended to resume reporting upon his return. But the vacation turned into a medical nightmare. As CNN reported, “he was struck down by a stomach bug” which got worse as he returned home; his symptoms expanded to include “constant diarrhea, a racing pulse, and general malaise.” And then, it hit his meal ticket — his voice. it “had suddenly become breathy, squeaky, unreliable,” and talking made it worse — “when Dupree opened his mouth to talk, his tongue would thrust out against his will. The more he tried to talk, the more it protruded, making it impossible to express himself.” That’s a big problem for a radio reporter — and doctors were stumped.

When he finally found out what was wrong with him in 2017, it wasn’t good news. Doctors at the Cleveland Clinic diagnosed him with focal dystonia, and specifically, tongue displacement dystonia. Focal dystonia, generally, is a neurological condition which results in involuntary muscle contractions, in effect causing the afflicted to lose some control over the associated body part. In the case of Dupree, the malfunctioning muscle was his tongue, making speaking difficult. (It’s not a coincidence that Dupree’s dystonia hit him where it mattered professionally; that’s often the case with dystonia, as seen in this list.) With a pen in his mouth to help keep his tongue back, Dupree can slowly muddle his way through sentences, but they come out slurred and difficult to understand, as seen in this video. Suffice it to say that he couldn’t take that voice onto the radio. Without a solution, his radio career seemed over.

But today — June 18, 2018 — Dupree is back on the air. He’ll just have a slightly different voice.

A Scottish company named CereProc caught wind of Dupree’s situation and offered to help. CereProc’s core product is a text-to-speech technology. They collect a large set of voice recordings from individuals and use that database to create a soundboard of sorts — you type in whatever you want it to say and, using those voice recordings, CereProc outputs those words as sounds. Most of those voices are generic ones like you’d expect from Siri and similar services, but CereProc can also replicate some celebrity ones. (You can play with those on their website, here, toward the bottom.)

In Dupree’s case, the dystonia meant he couldn’t sit down with CereProc to make a full recordings database. But that proved unnecessary. His decades of radio reports, CereProc believed, would be more than enough to populate the needed sounds. His new voice is a somewhat-robotic version of his old. But that’s OK — Dupree, in a blog post (which contains some clips of his new voice), proclaimed that “Jamie Dupree 2.0 is here – and I couldn’t be more excited about it!”

Bonus fact: The tone of one’s voice can be so powerful, marketers can use it to make subtle inferences which, they hope, only register on a subconscious level. One notable example: drug companies. Per STAT, a website focused on the news of the medical world, drug ads almost always have two narrators — a steady, confident one which tells about the affliction the drug treats, and a calm, soothing one which prattles off an extraordinarily long list of potential side effects. The goal — and a typically effective one — is to get consumers to not worry about the side effects which the manufacturers are legally mandated to disclose.

From the Archives: The Sound of Silence: The room where you hear nothing at all. Except maybe for your heart.