The Spring That Prematurely Ended a Magical Summer

If you’re in the business of selling cool, refreshing drinks, summer is an important season. And if you were to take a look at the Coca-Cola Company’s annual revenue on a seasonal basis, you’d probably not be surprised to see spikes when the warm months approach. Coke certainly knows this, too; in recent years, their “Share a Coke” campaign (the one with random first names on bottles) has become a harbinger of summer. In 2018, a Coke executive said as much in a press release (and yes, it’s overstated, but what do you expect from a press release?): “‘Share a Coke’ has become a rite of summer for our fans. The campaign’s annual return is a social marker on the calendar, as we welcome new adventures, new friendships and new memories.”

But not all of Coke’s summer marketing campaigns have been so successful. In fact, one was so bad, it didn’t even make it to summer.

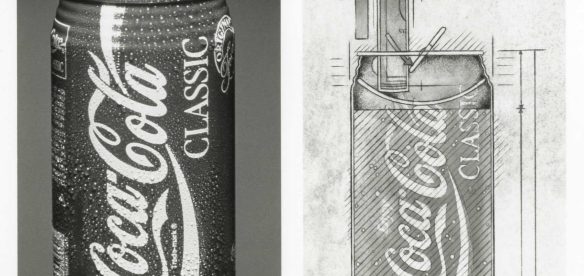

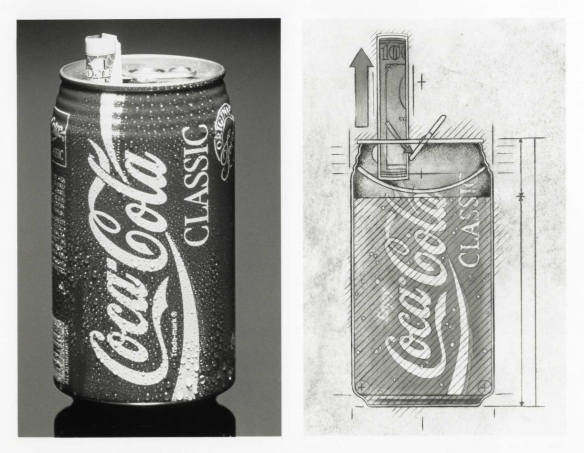

In the spring of 1990, Coke announced something called “MagiCans” — you can see a (grainy) ad from the campaign here. The stunt, the centerpiece to their $100 million “Magic Summer” marketing push, was simple. Some cans of Coca-Cola Classic were loaded with coupons, gift certificates, and most importantly, cash — up to $500. The prize cans were spring-loaded, as seen above; if the mechanism worked properly, the prize would pop up once the can was popped open. Those cans didn’t contain Coke, though; as the ad warned, “If you see anything other than Coca-Cola Classic in that can, don’t drink from it,” as prize cans were “winners” but, alas, didn’t contain any actual soda. Instead, they contained a sealed chamber of chlorinated water with a foul odor, intending to mask the weight of the prize while also stopping winners from taking a sip in case it somehow leaked.

Cans first hit shelves on May 7, 1990, and as Coke hoped, the promotion was initially a success — sales of Coke spikes as fans of the drink (and those who wanted to gamble a bit) literally bought in on the hype. Unfortunately for Coke, a small percentage of the prize cans malfunctioned — and some people ended up drinking the chlorinated water. The most notable example, according to the Chicago Tribune, took place in Massachusetts, when “a child reportedly opened a MagiCan that ‘exploded’. There was liquid in the can. The child tasted it, then spit it out; it tasted horrible. His parents called the police, who contacted the Coca-Cola Co. and state health officials.” (Despite some rumors to the contrary, the boy wasn’t harmed and most certainly did not die from tasting the foul water.)

That story and rumors of others began to spread. Coca-Cola tested the cans on the shelves, finding that only about 1% of the prize cans would fail, and told the press that in the first few weeks of the campaign, they received fewer than two dozen consumer complaints. But the bad press around the promotion was too much for the soft drink giant to overcome. Coke intended to distribute about 750,000 prize cans (out of about 20 million total) from May through the summer, but on May 31st — just weeks into a months-long initiative — Coke capitulated. The company announced that the MagiCans promotion was going to end prematurely and no new prize cans would be distributed. In total, only 200,000 of the prize cans made it to shelves, and the “Magic Summer” ended before summer even came.

Bonus fact: In 1993, Coke introduced an off-brand cola in hopes of attracting disaffected Gen X drinkers. Coming up with a name, though, was tricky, because as Wikipedia summarizes, “international market research done by The Coca-Cola Company in the late 1980s revealed that ‘Coke’ was the second most recognizable word across all languages in the world.” The only more recognizable word was “OK,” so the off-brand cola was named “OK Soda.” The branding didn’t matter, though; OK Soda tested poorly and didn’t sell well. It was gone from shelves before 1995 was out.

From the Archives: Where Coke and Pepsi Compete for Burps: An odd tale from the cola wars.