The Speed Trap That Trapped Itself

“To Protect and to Serve” is the motto of the Los Angeles Police Department, and it nicely sums up what a police department aspires to be. But for the small town of Stringtown, Oklahoma, there’s another step the police have to accomplish before they can be protectors of the community they serve:

They need to obtain to exist in the first place.

Stringtown is a tiny municipality in the middle of sparsely populated Atoka County, located toward the southeast of Oklahoma. Atoka County, as whole, is about 1,000 square miles (about 2,600 km2). Stringtown itself has only about 400 residents and yet, is somehow the second-largest town in Atoka (by population). It doesn’t have a lot of crime — an outsider would really, really have to go out of his or her way to rob whatever stores are there. And even then, the malfeasor would be in for a surprise — Stringtown’s largest employer is the Mack Alford Correctional Center, a medium-security state prison near the town. In short, Stringtown is a hamlet of correctional officers in the middle of nowhere — it’s not the place one goes to pull off the crime of the century. Rather, it’s the place you drive through on your way to somewhere else.

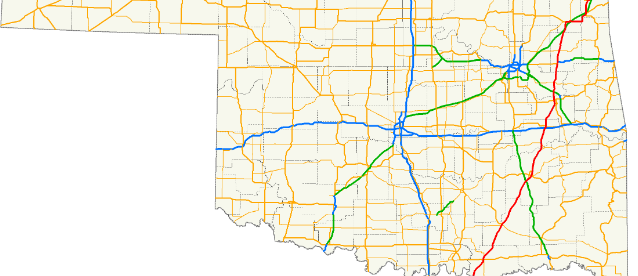

And yes, people do drive through Stringtown — or the surrounding area, at least — rather often. U.S. Route 69 in Oklahoma cuts through the state, running north to south, intersecting State Highway 43 in Stringtown. (Wikipedia has a map and route list, here.) And that proved too tempting for the Stringtown police department to resist.

Until 2014, the Stringtown PD was in charge of policing a five-mile stretch of Route 69, according to local news reports. And if you drove through that area of highway, there was a good chance you’d get a speeding ticket. The police were enforcing the speed limit strictly; according to the local news investigation, “most drivers who got speeding tickets were moving 10 to 15 miles over the speed limit,” which probably wasn’t a big public safety issue given the rather minor infraction and how little traffic runs through the area.

But for Stringtown, the tickets were important — not for safety, but for revenue. Stringtown doesn’t have much in the way of commercial activity; businesses have trouble staying in business. As such, it’s not so easy for the town to generate tax revenue. Stringtown, though, got to keep the money from the speeding tickets. So they wrote lots of them. According to the Oklahoman, “the town generated $483,646 in fines during fiscal year 2013, [representing] 76 percent of all Stringtown revenue. The year before, traffic fines accounted for about the same amount of cash, or 73 percent of all revenue in fiscal year 2012.”

That proved to be a few tickets too many. Under state law, towns can only generate no more than 50 percent of their municipal revenue through speed enforcement; Stringtown was way, way over that line. And the penalty for their own infraction was severe. Per CBS News, “state investigation found excessive speed trapping, and the police department was disbanded.” That’s right: Stringtown, Oklahoma isn’t allowed to have a police department.

If you’re one of the 400 residents, though, don’t worry — the county sheriff’s office still responds to 9-1-1 calls and other needs. As for Route 69, that five-mile stretch is now monitored by the Oklahoma Highway Patrol.

Bonus fact: If you’re looking to avoid speed traps, you may want to stay out of the eastern Virginian city of Hopewell. Interstate 295 runs through it for about two miles, and the stretch has a dubious nickname: the Million Dollar Mile. It gets that name from the aggressive ticket-writing from local law enforcement; per the above-linked CBS article, in 2014, the town “wrote more than 1,000 tickets per month.” Those citations added up: “Hopewell collected $1.8 million from tickets. The AAA said it’s one of the worst speed traps in the nation, despite the fact that traffic experts say there no safety concerns along that stretch of I-295.”

From the Archives: Life in the Fast Lane: Why speeding in Finland is worse than speeding in Oklahoma (or Virginia), at least if you’re rich.