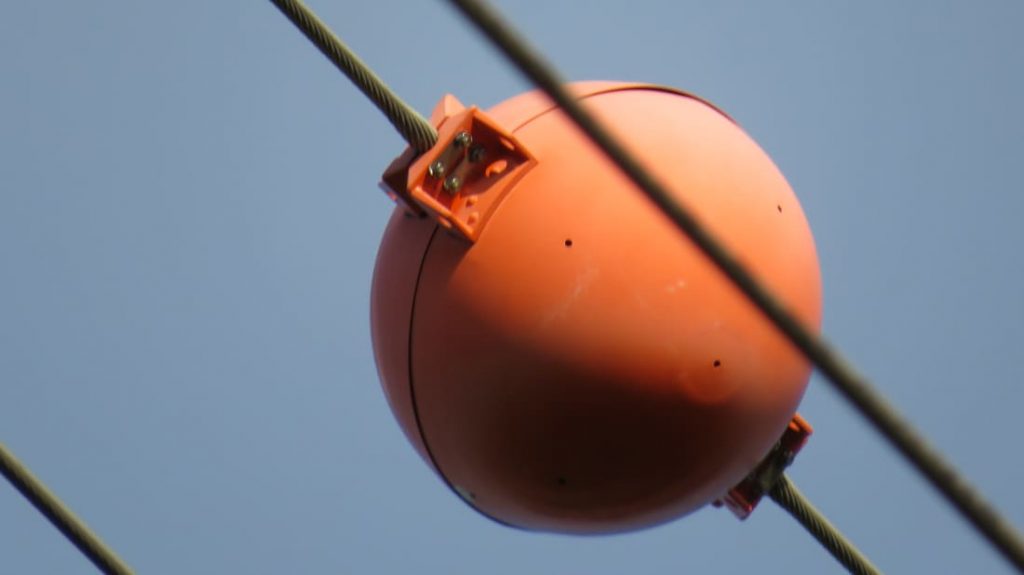

The Balloon Shields

Pictured above is a bright orange ball attached to an electrical wire. You’ve almost certainly seen them or something similar; they’re very common in many parts of the United States. And they have a simple and unsurprising purpose: they keep planes away. As Mental Floss delightfully explains, “though we sort of wish they were rogue holiday decorations local governments forgot to take down, the truth is that they’re actually used for aircraft safety.” The basic idea: you don’t want planes flying into power lines, but those power lines are hard to see. If you adorn them with bright orange balls, the pilots have something they can notice from a distance and adjust their altitude accordingly.

These have been around since the 1970s, but they’re not a new idea. We did something similar a century ago — before we even had power lines running through most of our cities — as seen below.

That picture (via here) was taken in London at some point in 1915. It features three balloons, each of which is holding up what appears to be some sort of cable. Between these three main cables are two sets of even more cables, forming what looks a lot like a net. And that’s exactly what it’s supposed to be.

Air warfare made its first emergence on the world stage during World War I, but by and large, fighting during the first World War was ground-based — each side dug trenches and, under the cover of artillery fire, would hope to advance forward from those trenches. Balloons helped in that effort; as Mashable explains, “observation balloon[s] would typically be floated to a great height behind the front lines, where an observer could locate distant enemy targets and relay their positions to artillery on the ground.” Seeing your enemy’s balloon go up meant a shelling was eminent, and so a typical response meant that you’d put your planes in the air to shoot down the balloons. Mashable continues: “these balloons were a tempting target for fighter planes, and so were heavily defended by ground-based anti-aircraft emplacements. If a balloon came under attack, its occupant would bail out, with a parachute automatically deploying upon leaving the basket.”

But the trenches weren’t near London, so the picture above isn’t showing observation balloons. Those are called “balloon aprons” or “barrage balloons” — basically, a balloon shield to keep the bombers away.

During the back-and-forth in the trenches, military tacticians noticed that while enemy planes were more than happy to shoot down the balloons — that was, after all, the pilots’ jobs — they weren’t flying too close. The artillery fire likely had a lot to do with that, but something else was happening, too: if the plane came in contact with the cable tethering the balloon to the ground, bad things would happen to the plane. In London, far away from the ground fighting, these balloon-and-cable combinations acted as a shield against enemy planes. The Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum explains:

Floating barrage balloons over a specific area prevented enemy aircraft from flying close enough to target the area from directly overhead with bombs or strafing fire. If an enemy aircraft was determined to attack, the balloons forced them to fly at higher altitudes (to fly over the balloons) making them more susceptible to larger caliber anti-aircraft gunfire. The balloons themselves could also destroy enemy aircraft, especially at night: the cables that anchored the balloons to the ground were very difficult to see and posed a risk to any aircraft that flew into them. An aircraft caught in a cable could be slowed down enough to stall or have a wing torn off.

The application for such use didn’t end in World War I, either. In 1942, after being subjected to German bombing raids, London installed new balloons to protect the city. And per the above Smithsonian article, barrage balloons were used in World War II, and you can see them in photos of the D-Day landing on that page.

Bonus fact: It’s not an accident that the balls on the power lines are often orange. “International orange” is a color (actually, a few different but similar-looking colors) commonly used to differentiate something from its surroundings so that nothing crashes into it. That’s why the Golden Gate Bridge is the color it is. Fearing that ships would crash into it during periods of heavy smog or otherwise low visibility, the government wanted to paint it a color that would stand out. Per PBS, the U.S. Navy wanted it to be pained with “highly visible yellow and black stripes,” but one of the bridge’s architects, Irving Morrow, convinced them to go with its now-distinctive hue.

From the Archives: Balloonacy: A bad idea involving a lot of balloons. A lot of balloons.