These Shoes Are Made for Talking

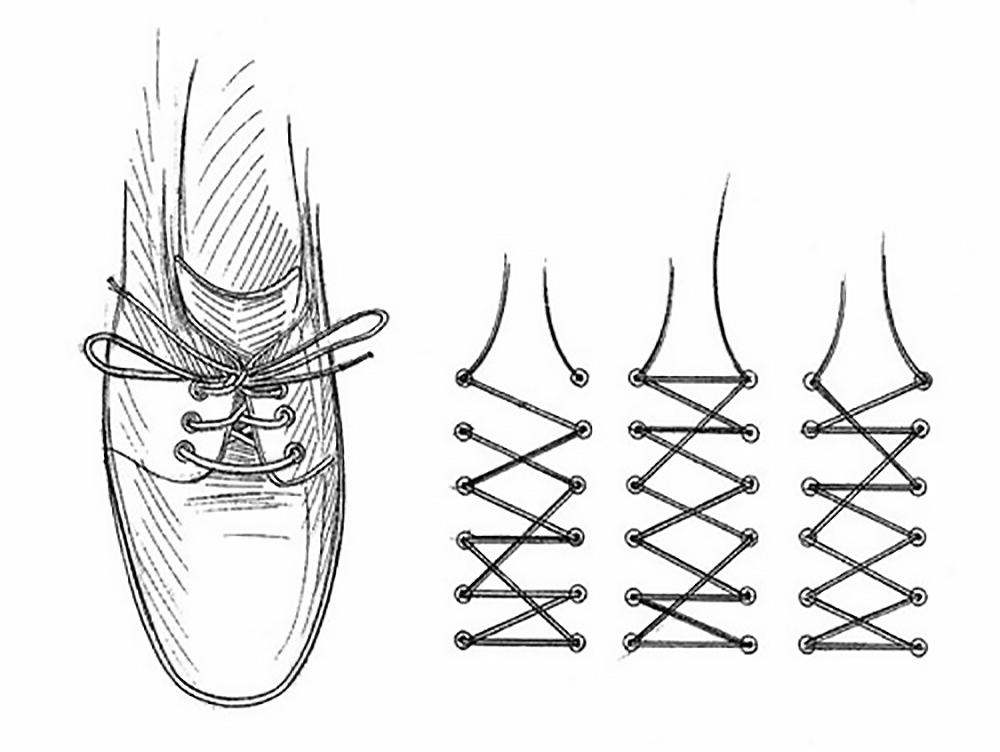

Pictured above is a photo showing three different ways to lace your sneakers. (The image comes from this video tutorial for how to lace your shoes, if you’re so interested, but it has little to do with today’s newsletter.) Most of us won’t bother to do anything like this — it takes a good deal of work, and a standard shoe lacing is good enough to ensure that your sneakers stay comfortably on your feet. But if you’re looking for a creative way to express yourself, shoelace designs are definitely an option.

And if you were a CIA agent during the early stages of the Cold War, you probably already knew that. Because it could have saved your life.

The Cold War was one of the scarier periods in geopolitical history; two nations, at odds with each other, each with an arsenal of weapons capable of killing tens if not hundreds of millions of people at the flip of a switch. Neither the United States nor the Soviet Union wanted to bring that doomsday scenario to bear, but each still needed to protect themselves from the other. Covert operations and espionage generally were a good way to do that — you get information and maybe even prevent your enemy from doing something contrary to your interests, and you do so in a way where it couldn’t be easily pinned on you.

But spy missions aren’t easy. First, you need to somehow embed your agent within an enemy institution — a task hard enough to begin with. From there, it doesn’t get any easier. While the operative can be given an initial task and instructions, you can’t communicate with them through regular channels without putting their cover at risk. Spies need a way to give and receive information without their targets discovering the ruse. And that’s tricky, to say the least — and the CIA and other spy organizations needed to be very, very creative.

So in 1953, according to the BBC, the CIA hired a man named John Mulholland to help, paying him $3,000 (the equivalent of $35,000 today) to write the first-ever “CIA Manual of Trickery and Deception.” Mulholland, though, wasn’t a spy — he was a magician. The manual outlined lots of different ways CIA agents could use the principles of illusionists to help them survive in the field and advance their goals. For example, as the BBC reported, the Manual “shows operatives how to conceal a doping pill in a matchbook, then covertly drop it into a person’s drink while distracting them by lighting their cigarette.”

And then it went further. Mulholland didn’t just teach them sleight of hand. He also gave them a way to communicate in silence — and in secret: via shoelaces. Here’s an image from a reproduced and edited version of the Manual, demonstrating what Mulholland suggested the spies do.

The idea was simple. Before embarking on a spy mission, the spy would connect with their handlers and agree on a series of messages that could be told via creative shoelacing. For example, the one on the left could mean “I’m in trouble,” while the second and third could mean “Mission complete” and “Come with me if you want to live.” It’s not likely that a Soviet would notice the shoelaces; I mean, seriously, how often do you really look at a man’s shoes? But even if they did, it wouldn’t matter, because according to a website dedicated to shoelaces (yes, that’s a thing, apparently), “each technique is only a slight variation of Straight European Lacing, which was likely the “standard” way of lacing agents’ shoes.” And in any event, the code was uncrackable: the secret message was specific to the spy-handler partnership.

It’s unclear if any spies used encoded shoelaces — if they did, the CIA hasn’t said (and may not even know, given the spy-specific nature of the trick). The CIA didn’t even want the Manual discovered. Per the BBC, the agency ordered all of the Manuals destroyed in the 1970s. One somehow survived and the content was ultimately turned into a consumer-purchasable book for about ten bucks.

Shoelaces are not included.

Bonus fact: Until recently, there wasn’t a formal study to help us understand why shoelaces become untied. That changed when mechanical engineers at the University of California Berkeley addressed the question in 2017. Per the school’s news site, “Using a slow-motion camera and a series of experiments, the study shows that shoelace knot failure happens in a matter of seconds, triggered by a complex interaction of forces. [ . . . ] When running, your foot strikes the ground at seven times the force of gravity. The knot stretches and then relaxes in response to that force. As the knot loosens, the swinging leg applies an inertial force on the free ends of the laces, which rapidly leads to a failure of the knot in as few as two strides after inertia acts on the laces.”

From the Archives: Why Pelé Tied His Shoes Before a 1970 World Cup Match: Advertising!