The Famous Symbol with the Hidden N and D

You’re probably familiar with the symbol pictured above. It’s the peace symbol, a widely-used shorthand used to object to the violence of war. It’s been around for more than sixty years, a testament to its simplicity — a circle encapsulating a vertical line and two leg-like branches. It’s iconic.

But it also wasn’t intended to be about peace, at least not generally. It’s a message advocating for nuclear disarmament. And its designer probably wishes he had turned it upside down.

Before 1958, only two of the world’s nations — the United States and the Soviet Union — had nuclear weapons. But the rest of the developed world was keen on getting in on the action. European nations joined the nuclear arms race shortly after World War II ended and as the spring of 1958 approached, the United Kingdom began its own nuclear arms testing. And not everyone was okay with that. As the Nuclear World Project explains, “a group of peace activists, clergy, and Quakers in Great Britain were organizing a rally to draw attention to the growing worldwide stockpile of nuclear weapons. The rally, which would eventually draw more than 5,000 people to Trafalgar Square in London, was to be a peaceful walk to the town of Aldermaston, the site of an atomic weapons research plant.” And like any good protest, they needed signs and flags and all that jazz.

That’s where Gerald Holtom, a graphic designer, entered the picture. He volunteered to design a logo for the movement and first came up with a design centered around a Christian cross. That proved unpopular, for many reasons. According to the UK’s Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, “various priests he had approached with the suggestion were not happy at the idea of using the cross on a protest march.” But Holtom likely would have revised it anyway; per Encyclopedia Britannica, he “disliked its association with the Crusades” and wanted something less aggressive. He decided to focus more on something directly related to nuclear disarmament.

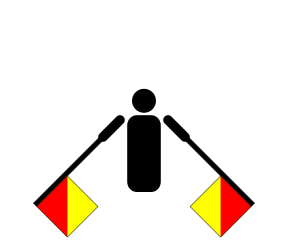

And that’s where the modern peace symbol came to life. Holtom looked toward the flag semaphore system, which, if you’re unfamiliar with it, is a way to communicate over long distances using (you guessed it!), flags. One uses the system by positioning two flags in one of 30 different positions, with each position corresponding to a letter of the alphabet or some other instruction (such as “reset” or “put a space between words here”). The signs for the letters N and D — the first two letters in “Nuclear Disarmament” — are seen, respectively, below.

The N signal involves sticking the two flags down and to either side; the D has them going up and down. If you put those two symbols together, you get the peace symbol (minus the circle). Don’t see it? Here’s a neat graphic, via CNN, that makes it clear.

The symbol has become more generalized over the decades since, which Holtom was proud of. But it was also, in his view, a missed opportunity. According to historian Ken Kolsbun, via CNN, Holtom had also “designed an upside-down version of the original, in which the letter ‘N’ was replaced by a ‘ ‘U’ to signify ‘unilateral’ disarmament, and he came to regret not using it.” (The flag semaphore position for “U,” as seen here, places the arms up and to either side, confusingly like the “Y” in the “YMCA” dance.) Whether unilateral nuclear disarmament would have actually led to peace is a question for another day and a different email newsletter than this one, but regardless, Holtman preferred that version over the one he created and helped popularize. Per Kolsbun, Holtom “wanted the inverted version to appear on his tombstone, but unfortunately, that didn’t happen.”

And it’s probably a good thing, for Holtom’s reputation at least, that an inverted peace symbol didn’t make it to his final resting spot. The origins of the peace symbol and its direct tie to nuclear disarmament has mostly been lost to history; having an upside-down one on his gravestone may have sent a message that he was anti-peace.

Bonus fact: Every year, the United States celebrates the birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. — but King’s birth nation isn’t alone in honoring him each year. As Atlas Obscura explains, the Japanese city of Hiroshima also marks his birthday — not for his legacy as an American civil rights leader, but as a global advocate for nuclear disarmament: “For decades, King spoke adamantly against the nuclear weapons that devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki, saying that further use of such bombs would transform the world into “‘an inferno that even the mind of Dante could not imagine.’”

From the Archives: The Two Soviets Who Saved the World: When the world came dangerously close to a nuclear war.