A City Fit For a King

Unfortunately, Atlanta was still racially segregated, and while King had many fans, he also had many enemies. Many whites were upset that King had been honored by the Nobel committee; one of the state’s senators, Herman Talmadge, expressed his dissatisfaction with the honor, wondering aloud why the committee gave a peace prize to a person who promoted lawbreaking. Invitations to the highly exclusive event came back with many more declinations than one would expect. A New York Times report claimed that a well-known (but unidentified) banker in the Atlanta area took to the phones, hoping to convince other whites to abstain from attending the banquet, and certainly, there were others preaching the same message.

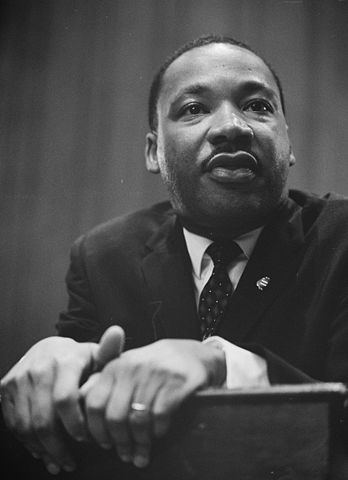

As the days ticked by, it looked more and more likely that the Dinkler Plaza Hotel — the site of the gala — was going to be rather empty on the evening of the event. Mayor Ivan Allen realized that such a result would be a stain on the city’s reputation, both immediately and forevermore, and also realized that it could set back the clock on racial relations in Atlanta significantly. He struggled to find a solution, but then, an unlikely hero stepped in.

Mayor Allen and J. Paul Austin, the chairman and CEO of the Coca-Cola Company, called together a meeting of the Atlanta’s business leaders, and Austin threw down the gauntlet. According to the Atlanta Constitution-Journal, Austin told those assembled that “it is embarrassing for Coca-Cola to be located in a city that refuses to honor its Nobel Prize winner. We are an international business. The Coca-Cola Company does not need Atlanta. You all need to decide whether Atlanta needs the Coca-Cola Company.”

They decided. Within two hours, all of the tickets were sold, and interest in the event skyrocketed so much that Martin Luther King, Sr. (yes, the honoree’s father) had trouble getting enough tickets for his own use. The Dinkler Plaza was stuffed to the brim with over 1,500 partygoers, and, perhaps most importantly, the police detail outside had nothing to do. The police were there to combat the hordes of protesters expected to descend upon and disrupt the party — but the threat never materialized.

Bonus fact: MLK’s birthday became a holiday in 1986, but some states were slow to adopt it. It would not be celebrated in all 50 states until 2000, and two states — Mississippi and Alabama — celebrate it in conjunction with the birthday of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, born January 19, 1807.

From the Archives: Dissolving Medals: When the Nazis came for gold, a scientist hid some Nobels — using science.

Related: “A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr.“

Leave a comment