Unmixed

On the fourth of July, 2010, a man named Kent Smith was on a cruise in the Gulf of Alaska. He started watching the water, as many cruise-goers are bound to do, and, in his words, noticed something strange: “I had been on the deck for quite some time when I noticed what appeared to be a shadow cast by clouds over the ocean about 5 miles in front of the ship. As we approached the shadow I realized it was something different.” That something different turned into the picture seen above (larger version here).

In the middle of the gulf, there were two bodies of ocean water, unmixed.

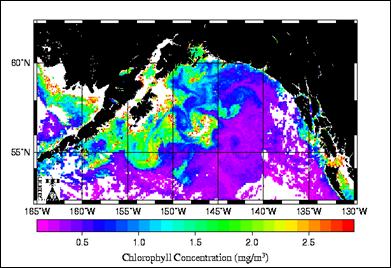

What’s going on there? The lighter water (left) are coastal waters while the darker waters are much typically further out in the gulf. They’re kept mostly separate due to the formation of large eddies — swirling water caused by currents collide into each other. The lighter water is made up of glacial runoff which is carried by the Alaska Stream. The Alaska Stream runs, roughly, from Kodiak Island down the Alaskan Peninsula (from A to B on this map). The darker water comes up to the gulf via the Alaska Current, which starts in the Pacific and then turns up the coast of British Columbia and into the gulf. The Alaska Current causes water in the Gulf of Alaska to run counter-clockwise, but when it hits the Alaska Stream, clockwise flowing eddies form. Ken Bruland, a researcher at the University of California at Santa Cruz, created an image of sea surface chlorophyll in the region, below (originally from here), which helps map out the eddies. (The light green region is where the eddies are.)

But eddies, while not terribly common, also are not so obvious to the naked eye. For that, Bruland and researchers associated with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) have an easy answer: iron. The coastal waters have a high amount of iron in it while the darker water has very little. The iron encourages plankton growth, which is most likely why there is a clear, visible difference between the two sides.

Bonus fact: What happens when two rivers come together? They mix — but not right away. In 2006, astronauts above the International Space Station took this photograph of the Ohio River (right, and brown) merging into the Mississippi at Cairo, Illinois. Per NASA, the photo shows an area about three to four miles downstream after the rivers converge, and as you can see, they are not yet mixed.

From the Archives: Assorted and Sorted: Why mixed nuts unmix.

Related: An ecosphere — a closed aquatic ecosystem. From the description, it is an “enclosed world [which] contains marine shrimp, algae and micro-organisms” and lasts, on average, two to three years.

Leave a comment