Leopards and Tigers and Corbetts

In the late 1800s, a Bengal tiger known as the Champawat Tiger was terrorizing Nepal. While tigers, typically, do not attack people unprovoked, the Champawat Tiger was the grand exception to this rule of thumb. Before the century was out, this particular tiger would kill at least 200 people. The Nepalese army drove it out of the country and into what is present-day India, where it continued on its rampage, killing at least another 200. Together, the Champawat Tiger was responsible for 430 known deaths.

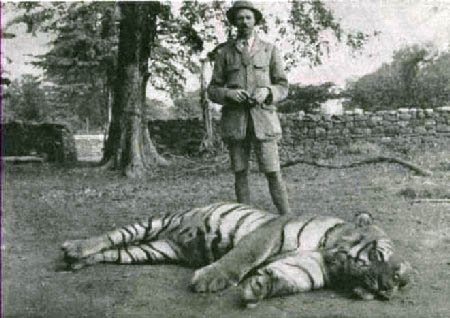

In the end, the Champawat Tiger met its match — a man named Jim Corbett, pictured above, standing over the aforementioned tiger. Corbett was not simply lucky, though. Corbett was a specialist — the guy you called when you needed to kill a man-eating tiger or leopard.

The Nepal/India region of the late-1800s/early-1900s was fertile ground for man-eating cats. The Champawat Tiger was the most successful in that regard — her 430 kills is regarded as a record. But she was not alone. Take, for example, the Leopard of Panar. After feasting for years on the corpses of people struck by various epidemics, the Panar Leopard found its food supply wane as those epidemics passed. So it began to hunt — for people. It is credited with killing roughly 400 people in the early 20th century in Northern India. Similarly, the Rudraprayag Leopard menaced a roughly 25 mile (40 km) path between the Indian villages of Kedarnath and Badrinath, each a home to holy shrines to Hindus. And similarly, he is believed to have developed the taste for human flesh due to the prevalance of corpses in and around his habitat.

Like the Champawat Tiger, these two leopards met their fate at the hands of Corbett. Add a couple dozen other man-eaters to his count, and Corbett is credited with eliminating 33 tigers and leopards who, combined, killed over 1,200 people over the course of 30 or so years.

Corbett’s methods were robust, a biproduct of his unique mix of skills. He was familiar with navigating the jungles of India and Nepal from a young age, being born and coming of age in the region. He had decades of experience hunting tigers — he worked with an illegal poacher as a teen. And he was a marksman to boot. As Damn Interesting describes, these skills, combined, allowed him to succeed where all others failed:

After months of stalking, Corbett marked one of the leopard’s favorite trails, set a goat as bait, and climbed into a mango tree. There Corbett spent ten nights, with only the anxious murmurs of the landscape hinting at the leopard’s proximity. Just before midnight on the eleventh evening, he heard the distinct clamor of the goat’s bell, and snapped on his weak flashlight. The beam caught a flash of pale fur, and a single shot rang out from the mango tree. The leopard disappeared into the gloom. Five hours later, when the clouds broke, Corbett left the safety of his tree to investigate. There in the silver light of the moon, he found the man-eating Rudraprayag Leopard dead.

Corbett believed that the tigers and leopards only attacked people as a last resort. The animals he killed all had one thing in common — they were significantly injured, and likely unable hunt their typical prey. The Champawat Tiger, for example, had two broken canine teeth. The Rudraprayag Leopard exhibited similar problems, as old age and gum disease had robbed it of a few teeth as well. Another tiger, known as the Chowgarh Tigress, had many undissolved porcupine quills in her leg, causing muscle and bone decay. In each case, these felines had to go after easier targets — and people, without any natural defense from tigers, were as good of a target as any.

To his credit, Corbett acted on this belief in later years. He devoted the end of his life to documenting the lives of the animals he previously hunted — the non-man-eating ones, at least — via photography, and helped establish a nature preserve in the region. He passed away in 1955 and, two years later, the nature preserve whose creation he spearheaded was renamed after him.

Bonus fact: According to the World Wildlife Fund, there are only about 3,200 tigers in the wild today, worldwide. As noted by National Geographic, as recently as 2005, there may be as many as 5,000 tigers living in captivity in the U.S., and most are kept as pets — “by private individuals, not zoos.” Note that in many cases, private ownership of tigers is not illegal. More than half of the U.S states — 31 of them — allow private citizens to keep wild animals as pets (and only 15 of those require that the tiger owner obtain license to do so).

From the Archives: The Apartment Not Too Far From 88th Street: The tale of one of the 5,000 pet tigers, formerly, and his similarly wild roommate.

Related: “Man Eaters of Kumaon” by Jim Corbett. His autobiography discussing his hunt of the man-eating tigers. 86 reviews averaging 4.8 stars.

Leave a comment