Off the Hook

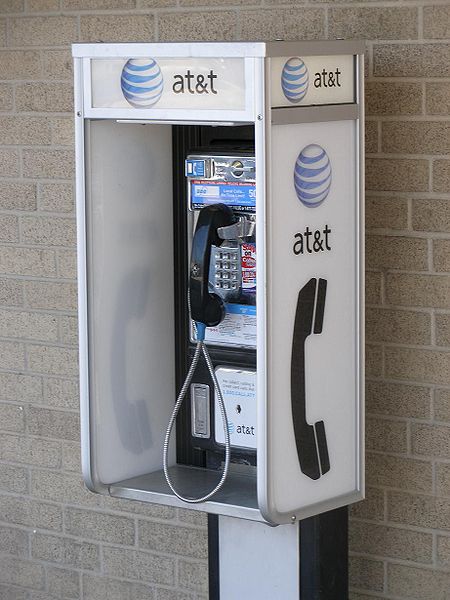

Over the last decade or so, cell phones have become as important to our everyday lives as any other object. And as one thing thrives, another wanes — in this case, the street-side pay phone. Once a staple of urban (and even suburban) life, coming across a pay phone now seems like a rare occurrence.

But in the mid-1990s — well before cell phones were common, let alone ubiquitous — the Malaysian state of Sabah on the island of Borneo found pay phones disappearing for another reason: someone was stealing them. Before long, 900 of the pay phones went missing, totaling about a quarter of those provided in the area by the local phone company, Telekom Malaysia.

The mystery of the stolen pay phones was strange to say the least, baffling authorities. Detached from their bases, the phones could not longer be used to place a call, and, therefore, were not obviously useful. And with no clear motive, Telekom Malaysia could not take decisive action in hopes of stemming the tide of thefts.

But in time, the culprit turned up — and the fishing industry was to blame. Some fish have been known to be lured in by sound as much as, say, chum or worms. According to the Independent, Malaysians sometimes bang bamboo sticks together underwater as a method for attracting a catch, and in the UK for example, the sound of a fly hitting the water has been known to attract fish, not scare them away.

For the Borneo fishermen, it turned out that the pay phones’ handsets made for good sonic fish bait as well. The fishermen were detaching the handsets, connecting a high-powered battery, and placing the handset near (or in?) the water. Also according to the same Independent article, the resulting sound attracted tilapia, grouper, and snapper to the phone, where the fishermen’s nets awaited them. (How the fishermen figured this out in the first place is anyone’s guess.) The bait worked better than worms or any other food.

How Telekom Malaysia prevented the theft of further phones — if at all — was left unreported.

Bonus fact: In 1990 — again, an era before cell phone ubiquity, and also, before the real-time information-on-demand we’re accustomed to today — finding out what happened at a baseball game (or any sporting event) outside of your local media market required waiting for the evening news broadcast or the next day’s newspaper. Pay phones helped change that, becoming a key ingredient in a scheme to get up-to-the-minute baseball scores, as recounted by Baseball Prospectus. In June of that year, Beckett Baseball Card Monthly magazine asked its readers to mail them with the phone numbers of pay phones at stadiums, ideally with a view of the scoreboard. In October, just in time for the playoff races, the magazine printed its findings. The idea? Fans at home could call the pay phones hoping that a fan in the stadium would pick up and read the scoreboard to them.

From the Archives: The 411 on Area Codes: New York City has 212. Across the country is 213, in Los Angeles. How did this come to be?

Related: A replica 1950’s pay phone, in red, with working coin slot. No idea whether it can attract fish, but it can probably be used to call someone to find out the score in a baseball game.>

Thank you to technology and culture historian Edward Tenner, author of “Why Things Bite Back” and “Our Own Devices,” for helping me track down a source for this story.

Leave a comment