Cresap’s War

In the early 1800s, it was clear that the issue of slavery was going to be a divisive one in the United States. In 1820, Congress came to a compact called the Missouri Compromise, making slavery legal in the South and illegal in the North. On the east coast, the shared border between Pennsylvania and Maryland divided the North from South. That line, known as the Mason-Dixon Line, has kept this traditional North/South distinction, culturally, even since slavery was abolished.

But the Mason-Dixon Line doesn’t hail from the Missouri Compromise. It predates it by nearly a century, when the then-colonies of Pennsylvania and Maryland could not figure out how to play nicely with one another.

In the early 1720s, Pennsylvania and Maryland were in the midst of a border dispute. Pennsylvania’s charter established its southern boundary “by a Circle drawne at twelve miles distance from New Castle Northward and Westward unto the beginning of the fortieth degree of Northern Latitude, and then by a streight Line Westward to the Limitt of Longitude above-mentioned.” The problem was that North Castle was about 25 miles south of the 40th Parallel, and, therefore, the 12 mile arc designated by the charter would never intersect with the rest of the border thereby established. This created a question as to where the true border should lie.

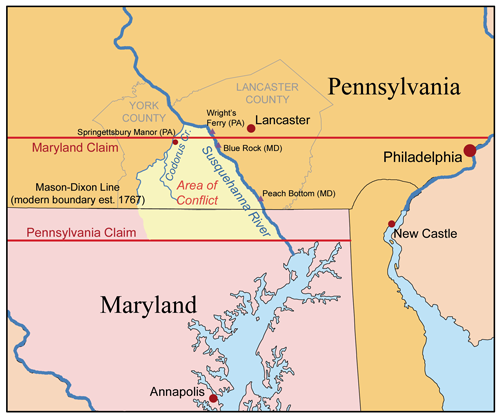

Maryland opted to ignore the reference to the circle altogether, and claimed that Pennsylvania’s southern border (and therefore Maryland’s northern one) extended eastward across the 40th Parallel to the Delaware River, as seen in the map above. Pennsylvania, on the other hand, argued that the Crown’s intent was clearly to put the border further south, and therefore placed the border at about 39 degrees and 36 minutes north, also noted above. Britain, via a royal proclamation in 1724, instructed the two to come to a compromise.

But a compromise was not going to come easily. Philadelphia, then the capital of the colony of Pennsylvania, was situated south of the 40th Parallel, and both colonies wanted that city within its borders. Despite the Crown’s mandate, Pennsylvania created Lancaster County, clearly extending south of the border as claimed by Maryland. Maryland responded in May of 1730. The colony authorized a frontiersman named Thomas Cresap to start a settlement where the 40th Parallel intersected with the Susquehanna River; Cresap did so with a “band of armed followers” per the Lancaster Country Historical Society (LCHS). According to Wikipedia, Cresap began selling land to Pennsylvania Dutch settlers and collecting fees from them, which he remitted to Maryland as a tax paid by these settlers.

But not all Pennsylvanians were so welcoming to Cresap and his gang — nor was Cresap so nice to his other-colony neighbors. In October of 1730, two Pennsylvanians raided Cresap and a workman on his ferry, casting both into the water. And while warrants ordering the assailants’ arrests were, eventually, issued, at first, the PA judge refused to do so, citing Cresap’s loyalties to Maryland. And Cresap and his men, for their part, were no better. Per the LCHS, Cresap’s gang “menaced their Pennsylvania neighbors,” destroying fences and even killing a horse which entered Cresap’s property. What would later become known as “Cresap’s War” had begun.

In 1732, leaders of both colonies agreed to a border roughly where the current Mason-Dixon Line is, but in 1734, the Governor of Maryland reneged on the agreement, claiming that some agreed-upon terms were omitted. And with that, all of Cresap’s malicious activities resumed. Hostilities escalated, and over the course of the next two years, both colonies sent their militias into the disputed areas to quell uprisings or, perhaps, start them. And Cresap kept raiding farms, now often burning them. On November 25, 1736, the sheriff of Lancaster County formed a posse and set out to arrest Cresap. Wikipedia describes this ordeal:

Unable to get him to surrender, they set his cabin on fire, and when he made a run for the river, they were upon him before he could launch a boat. He shoved one of his captors overboard, and cried, “Cresap’s getting away”, and the other deputies pummeled their peer with oars until the ruse was discovered. Removed to Lancaster, a blacksmith was fetched to put him in steel manacles, but Cresap knocked the blacksmith down in one blow. Once constrained in steel, he was hauled off to Philadelphia, and paraded through the streets before being imprisoned. His spirit unbroken, he announced, “Damn it, this is one of the prettiest towns in Maryland!”

And then, finally, the Crown interceded. In the summer of 1737, King George II issued a proclamation demanding that the conflict between the two colonies end; by and large, this was held to outside of some sporadic violence. The two colonies sent negotiators to London to work with royal mediators, and on May 25, 1738, they came to a peace accord which set a temporary border 15 miles south of Philadelphia, until the British courts could determine where the permanent border would be. And, under this agreement, the two colonies swapped prisoners, thereby freeing Cresap.

Eventually — in 1750 — the courts ruled that the agreement reached in 1732 was binding, and set the border at roughly 39 degrees and 40 minutes north. In 1767, two surveyors — Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon — drew the official line which now carries meaning well beyond its original history.

Bonus fact: Over the years, Pennsylvania and Maryland warmed up to one another, and even agreed upon a few things. One of the issues in which they are in agreement? That “ladies’ night” promotions run afoul of gender anti-discrimination laws. The only other states to do so are California and Wisconsin.

From the Archives: No Man’s Land: How a border dispute between Egypt and Sudan left part of the world unclaimed by any nation.

Related: “Drawing the Line : How Mason and Dixon Surveyed the Most Famous Border in America” by Edwin Danson. 18 reviews, 4.3 stars, available on Kindle.

Leave a comment