Rough in the Diamonds

On January 25, 1848, a man named James W. Marshall discovered gold in Coloma, California. As news spread, as many as 300,000 people came to the greater San Francisco area in search of similar fortunes; the California Gold Rush was in full force. Quickly, the prospector culture overtook the area and had a lasting effect on the city writ large; even the local football team, established in 1946, is named the 49ers because of the impact that the gold rush had on the growth and development of the city. So in 1871, when two men came to a San Francisco bank with a bag of diamonds, curiosities were understandably piqued.

Those two diamond-bearing men were cousins from Kentucky named Philip Arnold and John Slack. Learning the lessons from the Gold Rush, the pair were quiet about their gems, and decided to clam up instead of explaining where their new-found riches came from. And that made everyone even more curious. Their reluctance to talk about their mine lent credibility to the apparent value of their claim, and only when financiers and businessmen tracked them down did the cousins agree to let anyone come and visit where they allegedly obtained the diamonds from. Even then, the only visitor allowed was a mine inspector, who was brought to the site blindfolded in order to protect its true location, and was only invited after a group of investors came aboard. (Those investors included Charles Tiffany, founder of jeweler Tiffany & Co., and Horace Greeley, who just a few months later would unsuccessfully run for President.) The expert reported back that there were diamonds to be had, and the group of investors forked over $600,000 — which, in today’s dollars, would be well north of $11 million. And for a brief moment, a diamond rush broke out in Wyoming, Colorado, and the rest of the western United States.

And, just as quickly, the rush crashed — because there were no diamonds to be found. Arnold and Slack had pulled off a year-long hoax.

During the Gold Rush, con artists used to employ something called “salting” to prime interest in could-be mines. Buy a bit of gold or silver, sprinkle the dust all over the place, and hope that the mark either doesn’t know about the scam or falls prey to it. Salting efforts at times were incredibly complex; one (likely fictional) account tells the story of some swindlers planting a dead snake just as the claim inspectors were about to take their sample, just so they could fire their weapons — which had gold dust in the chambers — at the land they were about to scoop up. By the 1870s, most everyone was aware of such scams, but the promise of riches led many down a wayward path regardless.

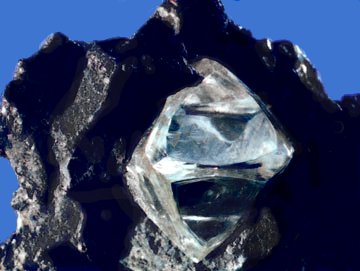

With temptation and curiosity both still very powerful, the Kentucky cousins hatched a salting plan of their own. The played the role of rubes and led “sophisticated” investors to a diamond-salted mine far away from San Francisco. Their Wyoming-area mine was salted with gems original from South Africa, obtained as cast-offs from diamond cutters in London and Amsterdam, and (according to one report) some of the diamonds even had tell-tale jewelers’ marks. It’s unclear why the investor’s expert was fooled by the scattered diamonds, but that success was short-lived. Another expert by the name of Clarence King (who later became the founding director of the U.S. Geological Survey) determined that the mine was a hoax, making headlines across the country. The swindlers by and large got away with the scam (although some former investors sued Arnold and recovered a small amount via settlement), and the brief diamond rush came to an abrupt halt.

Bonus fact: Lots of gold prospectors meant lots of people who needed stuff, so in 1853, a man named Levi Strauss and his family moved to San Francisco to open a dry goods store, known as Levi Strauss & Co., which sold combs, purses, bedding, and of course, clothes. In 1872, around when Misters Arnold and Slack were about to be uncovered as fraudsters, Strauss and business partner Jacob Davis introduced copper-riveted denim pants — what we now call blue jeans — to area workers.

While Levi’s jeans have persisted to this day, one part of them almost didn’t. The back pocket has a double arch design called. the “Arcuate,” seen here, over which the company holds a trademark. During World War II, the U.S. government ruled that the design served no practical purpose and was only decorative, and due to wartime rations involving cotton, did not allow the company to use thread in such a manner. To maintain the trademark (as the design needed to remain in use), the company painted the design onto the jeans.

From the Archives: Oil Baron: An even bigger hoax.

Related: Eight dollars and fifty cents worth of fake diamonds, numbering 800 in total, for your diamond mine-salting needs.