Do You See What I See?

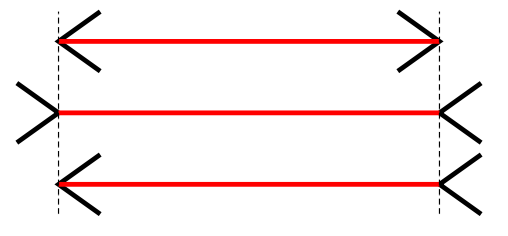

The image above — yes, an arrow — is actually, in this case, an optical illusion. In 1889, German sociologist Franz Carl Muller-Lyer devised the following test: Look at the arrow above and put a mark on the midpoint of the horizontal line. Without exception, his test subjects believed that the midpoint was further to the right side than it should be. The stylized arrowheads, Muller-Lyer believed, caused the illusion that the line extended further to the right than it actually did.

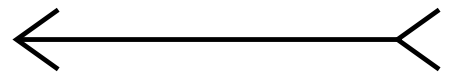

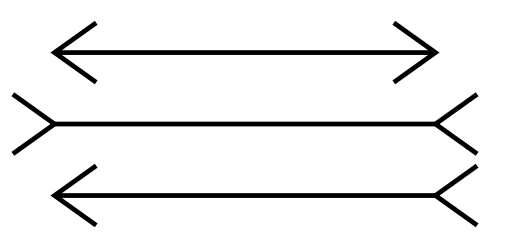

Over the years, the most common version of the illusion has been modified to appear as it does above. Two additional sets of lines are bound by arrows, one with the arrows pointing out, the other with the arrows pointing in. The former should appear shorter than the latter. But as seen below, all three lines are actually the same size.

We don’t know what causes this. The most common explanation is that our brains perceive a third dimension — depth, as seen in this image — and accounts for that dimension in its measurement estimation. Regardless, chances are that if you’re reading these words, you will “see” the illusion and require the red-lined image above to be convinced that the lines are, in fact, of equal length. But not everyone is susceptible to the visual trick.

Some cultures don’t fall prey to it at all.

In 1963, a team of researchers decided to test the Muller-Lyer illusion among people in sub-Saharan Africa. While the illusion worked, without fail, among the Americans and Europeans (and South Africans of European descent) that were tested, they wondered if the same would apply to people of less developed societies. It didn’t. As reported by Smithsonian Magazine, the researchers showed similar images to bushmen from various tribes in Angola and the Ivory Coast. Many of them did not see the illusion at all, and were able to correctly “see” that the lines were of the same size.

Why this happens is unknown, but it throws a wrench into the generally favored theory as to why the illusion occurs in the first place. Redoubling that doubt? A recent study focused on a computational model which modeled the visual behavior of those fooled by the Muller-Lyer illusion, and found that the computer was, also, fooled. However, the computer was not exposed to any three-dimensional models, suggesting that the common explanation referenced above is incorrect.

Bonus fact: In the year 756, China’s Tang and Yan Dynasties fought at the Battle of Yongqiu. The Tang Dynasty won the battle (and, while suffering large losses, would also win the war, known as the An Shi Rebellion), and resoundingly, with losses of only about 500 to the Yan’s 20,000. One of the tactics the Tang Dynasty used in this triumph involved mannequins, which were lowered down from castles. The Yan archers would fire at the mannequins, unsure whether the human-shaped targets were real or fake. In doing so, the Yan forces not only were depleting themselves of ammunition, but also replenishing the supply of arrows for the Tang soldiers.

From the Archives: Leaning Out: Another illusion.

Related: “The Ultimate Book of Optical Illusions” by Al Seckel. 47 reviews, 4.6 stars.