Something Old, Something Blue

The Battle of Gettysburg is generally considered to be a symbolic turning point of the American Civil War. Seeing the opportunity to greatly weaken Northern resistance to Southern independence, Confederate General Robert E. Lee brought more than 70,000 soldiers — perhaps as much as 10% of the total number of men who would serve under the flag of the South — northward toward Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in the late spring of 1863. Capturing Gettysburg, Lee surmised, would give the Confederacy a central point from which they could attack Philadelphia, Washington, or Baltimore; further, a successful encroachment into the area would provide the Confederate Army with supplies and farmland which would replace those lost from battles in Virginia. Further, many — Northerners and Southerners alike — believed that a Southern victory that far north would embolden peace advocates in the North, who were beginning to form a critical mass. But as we all know, the South lost the battle, and was unable to obtain these strategic gains. To the contrary, repelling the Southern attack gave the North confidence that they could successfully triumph over their erstwhile country-mates, and created a narrative of Northern resilience.

And it helped that there was a 69 year-old man who wouldn’t take no for an answer.

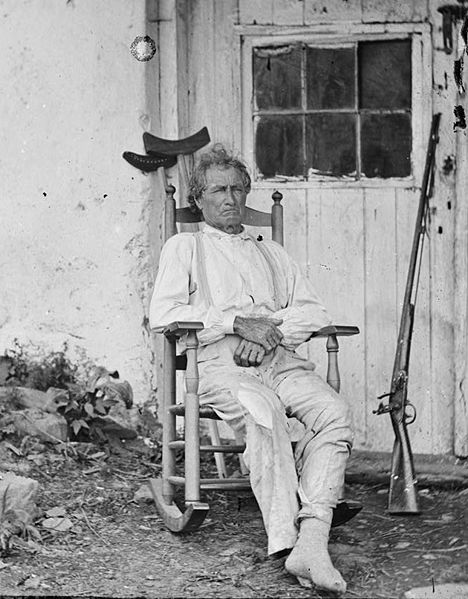

Earlier in the war, a man named John Burns tried to join the cause of the Northern army. But he was turned away by Union enlistment officers, who said he — then in his late sixties — was simply too old to be of any use. Instead, he was sent to Gettysburg to act as a local constable, a peace officer. As the South advanced northward, many in service to the North deserted and others, not yet enlisted, forcibly refused to be drafted. But when the war came to Gettysburg, Burns, then age 69, did the opposite. He grabbed his gun — a flintlock musket, a weapon long surpassed by advancements in military technology — and went to the field of battle.

He was almost turned away again, but needing any support they could muster, the Northern military leadership found a role for him. And that turned out to be a lucky gamble, as Burns wasn’t just a random retiree with a decrepit weapon. Unbeknownst to Union leadership, he had served for the U.S. Army in the War of 1812 and was an accomplished sharpshooter. He ended up picking up a more modern firearm from a wounded Union soldier and joined up with the 7th Wisconsin Infantry during the battle. Of the 90,000-something troops who fought for the North in the battle, Burns was not, officially, one of them. But he quickly became a very famous one.

There is no count — official or unofficial — which totals up the number of Confederates Burns shot during the battle, and his achievements are mostly overstated. (The Confederates suffered more than 20,000 casualties during the three days; Burns simply could not have been responsible for a meaningful percentage of that.) But Burns’ alleged successes, whatever they were, quickly became legendary throughout the Union. One account claims that he managed to shoot a charging Southern officer, knocking him off his steed. Another told the tale of how Burns kept firing despite being wounded twice; only when he took a third bullet did he fall. And when Confederate soldiers picked him up, instead of summarily executing him (combatants not in uniform were considered bushwackers and not taken as prisoners), he told them that he was looking for his wife and got caught up in the crossfire. He was returned to the North where he became known as the “Hero of Gettysburg.”

To a large degree, Burns became the symbol of Northern grit and determination. American poet Bret Harte penned an ode to Burns’ heroism. Civil War photojournalist Timothy O’Sullivan, whose work covering the war is one of our few visual primary sources about its goings-on, made a point to visit Burns as he recuperated back in Gettysburg. (This photo of Burns sitting in his home may have been taken by O’Sullivan; the one of Burns above certainly was.) Burns’ celebrity made its way to Abraham Lincoln, who insisted upon the having the constable present when he gave the Gettysburg Address.

Burns lived until 1872, nearly ten years after Gettysburg. His legend persevered much further. He is buried in Evergreen Cemetery, a site upon which part of the Battle of Gettysburg itself was waged. Burns’s grave is one of two — the other being that of Ginnie Wade, the only civilian who died in the battle — which is allowed to fly the American flag above it at all times.

Bonus fact: The Battle of Gettysburg lasted three days, but one controversy around it still exists today. During the battle, a unit from Minnesota managed to capture a Confederate flag from a unit from Virginia. The troops took the flag back to Minnesota and, somewhere along the way, the flag ended up in the Minnesota Historical Society’s possession. Well more than 150 years after the war, Virginia demanded that it be returned, but Minnesota refused, even though all other captured battle flags still in existence have been returned to their original states. To date, the flag is in Minnesota.

From the Archives: McLeaned Him Out: A strange coincidence from the Civil War.

Related: A biography of John Burns.