Let’s Call it a Draw

William Shakespeare once famously asked, “What’s in a name?,” with Juliet wondering aloud whether our names should determine our destinies. She was talking more about last names than first names (unless one’s name is Rose, maybe?) but no matter — the question is still an interesting and, to a large degree, unresolved one. It’s so interesting that, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, one New York City family decided to run a very informal experiment — one with limited scientific value, to say the least.

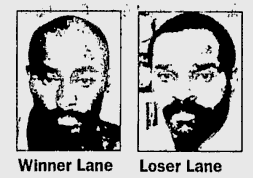

That family was the Lane family. In 1958, the parents had a son and named him Winner. Three years later, they had another son, their eighth and final child. Needing a name, the parents asked their oldest daughter for suggestions, and — this is why you should never let your children name their siblings — she said that they already had a Winner, so why not a Loser? So in 1961, Winner Lane became the older brother of a new baby named Loser Lane. (The daughter’s name was Dinelda, neither Lois, Tie, nor Draw, in case you were wondering.)

The two grew up in the projects in Harlem and, later in life, would both agree that their names didn’t seem to matter to those in their community — no one, at least outwardly or obviously, assumed Winner was awesome or that Loser was a loser.

Any such assumptions would have turned out wrong anyway (assuming those attitudes would have had a negligible impact on their lives, of course). For if you fast forward until their late-30s or early-40s, the pair’s names showed even less relevance. Winner earned himself an ID number — 00R2807. That was the number given to him by a state correctional facility during his two years in prison, the culmination of a decades as a small-time crook. (This was as of the summer of 2002; no one has seemed to follow up on the brothers’ lives since.) Winner’s record included a bunch of car break-in, some domestic violence charges, etc., all totaling well over two dozen arrests. When not behind bars, he often found himself broke, living at homeless shelters.

The good news is that he could call his brother Loser and ask for money. Loser Lane also had his own ID number — 2762 — and also like Winner, Loser’s ID had to do with his ongoing entanglements with law enforcement. That’s because, as of July 2002, Loser Lane was a police detective, and 2762 was his shield number. He worked out of the South Bronx and, by all accounts, was well regarded by his peers. This was the culmination of a successful childhood and life as a young adult; Loser was both an excellent student and athlete, and ended up attending a private prep school in Connecticut before gaining admission to Lafayette College in Pennsylvania.

As for the name itself, Winner’s seemed to stick — not in how his life turned out, of course — and people tended to call him that as both a teen and adult. Loser, though, wasn’t a loser in life or in name. As he recounted, most people felt uncomfortable calling him by his birth name — who wants to call someone a loser to their face, even if it’s their name? — and he’s come to be called “Lou” as an adult.

Bonus Fact: Salvador Dali (the famous artist) was named after his brother Salvador. The older Salvador Dali died nine months before the younger’s birth. The younger, surviving Salvador Dali was told by his parents that he was a reincarnation of his deceased brother, according to Wikipedia. He reportedly carried this for much of his life, and at age 59, the artist released a work titled “Portrait of my Dead Brother,” seen here.

From the Archives: John Wilkes Booth’s Heroic Brother: The very different destinies of two sons from the same family.

Related: O Brother, Where Art Thou? — it’s not really related, but it’s an excellent, must-see movie.