How the Aurora Borealis Almost Sent Humanity Over the Brink

On October 27, 1962, the world held its collective breath as Cold War tension between the United States and the Soviet Union neared its breaking point. The Cuban Missile Crisis — a standoff between the two superpowers over the presence of Soviet-owned ballistic missiles positioned just 100 or so miles from the United States — threatened to throw the world into nuclear war. The fact that we’re all here today is all the proof we need that World War III didn’t begin on that date, but it was close.

And the fact that the United States accidentally invaded the Soviet Union that morning probably didn’t help.

At midnight local time in Alaska, Captain Chuck Maultsby, a U.S. Air Force pilot, took off on a one-man mission taking him to the North Pole and back. American intelligence believed that the Soviets had tested nuclear missiles recently in Siberia. These tests sent untold amounts of radioactive materials skywards. Many of the clouds, especially a handful of them near the North Pole, promised to hold a treasure trove of fallout from the tests — a treasure trove of information for the scientists on the American side. Maultsby’s mission: pilot a U-2 spy plane to and from the North Pole, collecting samples when his Geiger counter told him to. The entire trip should have taken about eight hours.

But it wasn’t a straightforward flight — not even by design. Because he was flying a spy mission, radio silence was the rule — he couldn’t have the Russians finding out about his objectives. And because the mission was so close to the magnetic North Pole, his compass wasn’t effective. The conditions of the mission required that Maultsby navigate his way to and from the collection spot by relying on the stars. Armed with star charts and a sextant, Maultsby made his way north by way of the skies.

And then, something like this got in the way.

That’s the aurora borealis, also known as the Northern Lights. That’s not a picture from the night in question, but the idea is still the same. It’s big, bright, and beautiful — and it blocks a lot of the stars, too. That caused a major problem for Captain Maultsby; he wasn’t able to figure out where to go. So he guessed — and guessed poorly.

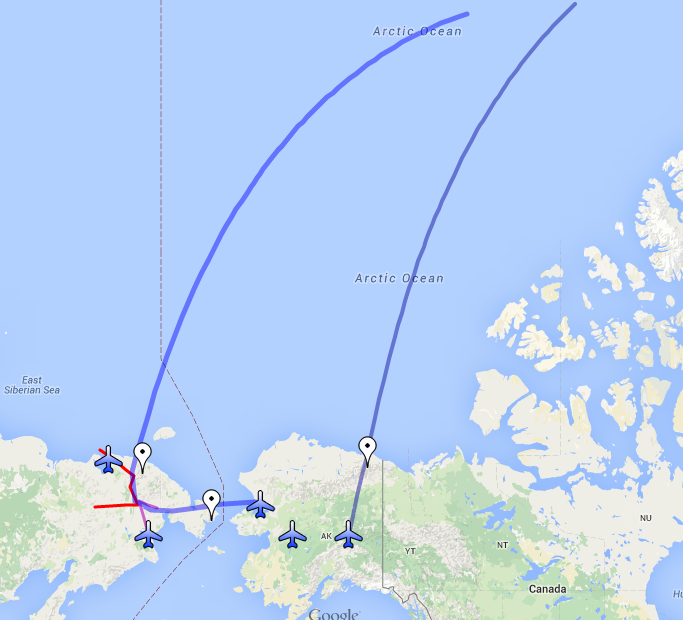

The National Security Archive at George Washington University put together the above map (as well as a better, Google Maps-based version, with labels, here) of Maultsby’s flight. The trip toward the North Pole went fine. The trip back? Not so much. Maultsby ended up in Soviet airspace, miles into the Chukotka Peninsula. But he didn’t know that.

Both the Russian and the American militaries, however, did. The Americans were on the radio, instructing him how to get him back into U.S. airspace. But, as historian Michael Dobbs noted in his book “One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War” (excerpted by Vanity Fair), they weren’t alone:

Shortly after receiving this instruction, Maultsby got another call over his sideband radio. This time the voice was unfamiliar. Whoever it was—and the presumption must be that the Russians were trying to lure him in—used his correct call sign and told him instead to steer 30 degrees right. Within the space of a few minutes, Maultsby had received calls from two different radios, ordering him to turn in opposite directions.

And to make matters worse, at least a half-dozen Soviet fighters were sent airborne, ordered to shoot down Maultsby’s plane. From the Soviet Union’s perspective, Maultsby’s trip was too dangerous to ignore. As Discover Magazine summarized, “the already-paranoid Soviet leaders would assume the pilot was on a secret mission to drop the first bomb of the Third World War while everyone was distracted by Cuba; an American U-2 pilot had been shot down over the island just hours before.” Had the Soviets downed a (lost) American plane during the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, who knows what that would have led to, but chances are, it wouldn’t have been very good for anyone.

Thankfully for Maultsby and for that matter, the world, a Russian radio station (music, not military) came over Maultsby’s speakers, clueing the pilot in on his true location. He turned eastward, hoping to get back to Alaska. And even though his fuel ran out along the way, the U-2’s extra-long wingspan allowed him to glide for miles and, ultimately, to safety.

Both U.S. President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev were made aware of the incursion — and its accidental nature — by their respective militaries. Khrushchev, according to Dobbs’ book, sent a note to JFK, noting that the event could have pushed an already tense situation in Cuba over the edge: “One of your planes violates our frontier during this anxious time we are both experiencing when everything has been put into combat readiness. Is it not a fact that an intruding American plane could be easily taken for a nuclear bomber, which might push us to a fateful step?” But cooler heads prevailed.

The two parties resolved the Cuban Missile Crisis the next day.

Bonus Fact: The U-2 planes were difficult to fly due to their design — very light, long wingspan, and non-traditional landing gear, among other things. (Here’s a picture of Maultsby’s.) The military selected top pilots for a special program, teaching them how to fly the plane. The training program took place at Area 51, the remote U.S. military base best known for the claims of UFO sightings by those in the area. As Wikipedia notes, the U-2 program may have furthered such conspiracy theories: “[alleged UFO] sightings occurred most often during early evenings hours, when airline pilots flying west saw the U-2’s silver wings reflect the setting sun, giving the aircraft a ‘fiery’ appearance.” Many if not all of the “UFOs” were just military planes on secret training runs.

From the Archives: The Two Soviets Who Saved the World: Two other thermonuclear war near misses.

Take the Quiz: Soviet leader or NHL player — can you tell the difference?

Related: “One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War” by Michael Dobbs, an in-depth view of the Cuban Missile Crisis. 4.6 stars on 130 reviews.