As the Ball Doesn’t Bounce

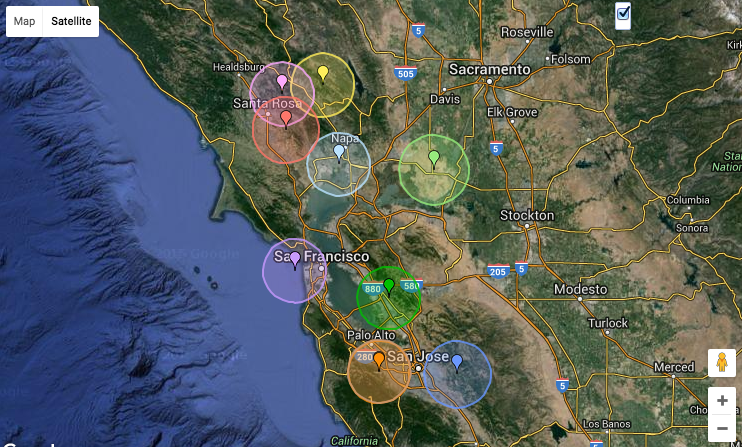

The San Francisco Bay area is home to an extraordinary number of earthquakes. The map above shows the location of earthquakes, ranging from a 1.5 magnitude to a 2.6 magnitude, all of which took place over a recent ten day period — selected because it was recent, not because it was particularly active. According to Earthquake Track, for a one year period ending on March 24, 2016 (when I wrote this), the San Francisco Bay area experienced more than 650 earthquakes of magnitude 1.5 or greater — more than a dozen earthquakes a week.

Such seismic activity makes building anything a bit risky, but life goes on, and the people of San Francisco need major public works. For example, San Francisco is home to an international airport — aptly named San Francisco International Airport (SFO) — which boards around 25 million passengers a year. It’s one of the busiest in the world. And despite its location, it’s only been minimally affected by earthquakes — even in 1989, when San Francisco was hit by a 6.9 magnitude quake (one which killed more than 60 people and left thousands injured), the airport’s service was barely disrupted. It shut down for the remainder of that day as a precaution and for safety inspections, but reopened the next morning.

So, how does one keep a billion-dollar airport from cracking? You add a lot of very big ball bearings.

SFO is situated on top of 267 pillars. If these were normal pillars, an earthquake would be catastrophic. The tremors from below would ride up the pillars, cracking some and causing parts of the building above to collapse. Further, any pillars which didn’t crumble would instead transfer the force of the earthquake to the building, resulting in a different type of carnage. In either event, it’s a bad result.

But these aren’t normal pillars. They’re equipped with something called the Friction Pendulum System.

Each of the 267 pillars is actually made of two separate parts which do not directly come into contact with one another. The bottom part is concave — imagine a shallow soup bowl — and at its lowest point (thanks, gravity!) rests a huge, very smooth metal sphere — 5 feet in diameter — which is, basically, a ball bearing. On top of the incredibly smooth ball is the rest of the pillar, leading up to the airport terminal itself.

In an earthquake, the ground may move as much as 20 inches in any direction. But as HowStuffWorks notes, the ball bearings prevent a lot of that movement from translating upward — “the columns that rest on the balls move somewhat less than this as they roll around in their bases, which helps isolate the building from the motion of the ground.” (HowStuffWorks has a simple, interactive demonstration of the effect if you click that link.) Or, as a civil engineering blog explains, “when the ground moves, the bearings move too, but the building does not. No force is therefore transferred to the building, meaning that (in theory), the building does not experience the earthquake.”

The ball bearing system isn’t quite that efficient — if the ground below is rumbling mightily, the building above will rock a bit — but it’s more than good enough. The company that makes the system says (pdf) that the bearings “reduce earthquake force demands on the building by 70%.” Further, the company notes that SFO can withstand an 8 magnitude earthquake. The last time the area experienced something greater? Never. The biggest earthquake in the area’s history — the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake — topped out at a magnitude of 7.8.

Bonus Fact: Because of the 1906 Earthquake, San Francisco is home to a golden fire hydrant. (It’s not made of gold; it’s just painted that color.) A massive, horrible side effect of the 1906 quake were fires — caused by ruptured gas lines — which raged throughout much of the city unchecked. In many areas, water mains also broke, which meant that the fire hydrants ran dry. San Francisco’s Mission District was almost no exception to this curse, but one hydrant — next to Dolores Park at 20th and Church, for those who know the area — was able to feed the hoses which drenched the flames. As Roadside America notes, “every year since the 1960s, on April 18 at 5:45 am, a ceremony is held in which relatives of the disaster’s survivors spray-paint the hydrant with a fresh gold coat.” Although, per Atlas Obscura, that hasn’t always been the case: “in 2012, the hydrant was accidentally painted silver, but it was quickly re-painted in its rightful gold color.”

From the Archives: Early Warning Lemurs: Perhaps the San Francisco Airport just needs a zoo?

Take the Quiz: Which states have the most earthquakes?

Related: “San Francisco Is Burning: The Untold Story of the 1906 Earthquake and Fires” by Dennis Smith. 4.6 stars on 30 reviews.